Terry O’Neill – who died on 16 November, aged 81 – was one of a number of working-class interlopers who kicked open the doors of capital-S Society just as Sixties London began to swing, and redefined photography in the process. Alongside such names as David Bailey, Terence Donovan and Brian Duffy, he pioneered a style that was closer to reportage and street photography than it was to the formal studio portraits of preceding decades.

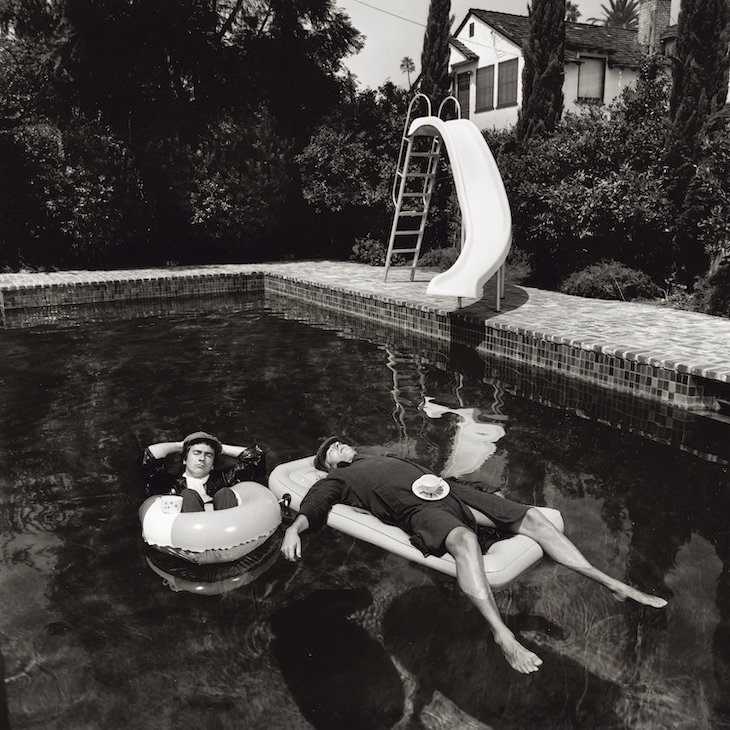

Peter Cook and Dudley Moore relaxing in a Beverly Hills swimming pool while in costume as the characters Pete and Dud, 1975. Photo: Terry O’Neill/Iconic Images

O’Neill’s early dreams of becoming a jazz drummer did not come to pass, but by the age of 20 he had developed a career – via an early gig as a departure-lounge photographer for the British Overseas Airways Corporation – as the youngest snapper working on Fleet Street. He shot the Beatles in a St John’s Wood back garden before they had even broken the Top 10 (‘I didn’t know how to work with a group, but because I was a musician myself and the youngest on staff by a decade, I was always the one they’d ask’), and within a few months was kitting out the Rolling Stones with suitcases to look like a travelling band in a series of candid street shots. His portraits, in grainy 35mm black-and-white, are a veritable roll call of the 1960s youthquake – Michael Caine, Terence Stamp, David Hemmings, Marianne Faithfull, Jean Shrimpton (walking barefoot on a rain-slicked King’s Road, or posing with the porcelain inmates of a dolls’ hospital) – and of the other stars of the age, from the Rat Pack to Muhammad Ali. He photographed Churchill being carried from hospital in an armchair, a potentate on a palanquin; shot Peter Cook and Dudley Moore floating on lilos in raincoats; and extensively documented the early career of Elton John – including a remarkable shot where he plays an upright piano with his legs floating up towards the ceiling, as if performing on the International Space Station.

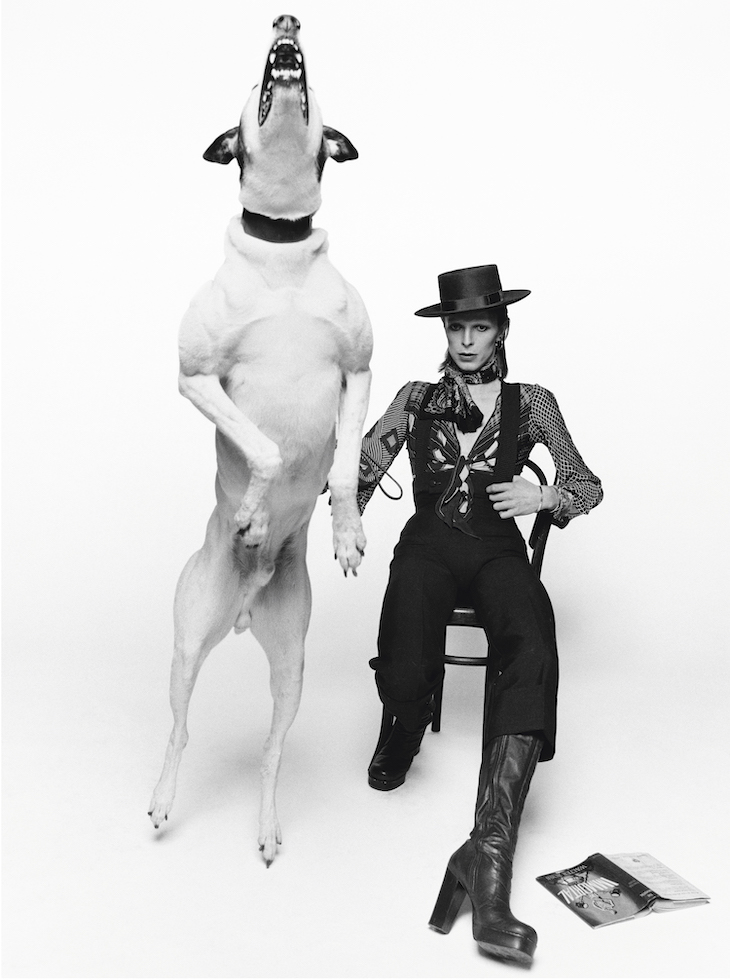

David Bowie poses with a large barking dog for publicity shots for his 1974 album Diamond Dogs in London. Photo: Terry O’Neill/Iconic Images

Even when O’Neill did work in the studio, spontaneity remained a key factor. A chance remark from Raquel Welch about being ‘crucified’ by the press led to an iconoclastic portrait of her tied to a cross in the prehistoric bikini she wore in the Hammer film One Million Years B.C. (1966). (The photograph remained unpublished for more than 30 years. ‘I lost my nerve,’ its creator said.) The famous sessions for David Bowie’s LP Diamond Dogs (1974) had a similarly serendipitous quality. Bowie, in a stack-heeled flamenco get-up, sits languidly on a Thonet chair, holding on a short lead a vicious-looking hound. The dog reacted angrily to the light of the flash, leaping up and snarling every time it went off. Bowie, however, appears entirely unfazed. ‘He didn’t turn a bloody hair,’ recalled O’Neill. ‘Mind you, he was zonked out at the time – all the time.’

Faye Dunaway at the Beverly Hills Hotel, 29th March 1977. Photo: Terry O’Neill/Iconic Images

One of O’Neill’s most celebrated portraits, The Morning After, depicts Faye Dunaway in early 1977. As the dawn rises over the pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel, the morning papers lying on the patio like autumn leaves, Dunaway reclines in a pool chair, almost horizontal, the Academy Award she had won the previous night sharing the table with a breakfast tray. It’s an image of dissolution and exhaustion worthy of Visconti – but one that is pregnant with possibility. Dunaway seems to be contemplating what her post-Oscar future might hold. In part, it involved a life with the man behind the lens – she and O’Neill eventually married in 1983.

Terry O’Neill. Photo: Misan Harriman/Iconic Images

In more recent decades, O’Neill largely retired from photography. He would return to the fray if the subject was right – the Queen, Nelson Mandela, Kate Moss, Amy Winehouse – but for the most part preferred not to, holding that present-day ‘celebrities’ did not have the star quality of their predecessors. And looking at his portfolio, it’s hard to disagree.