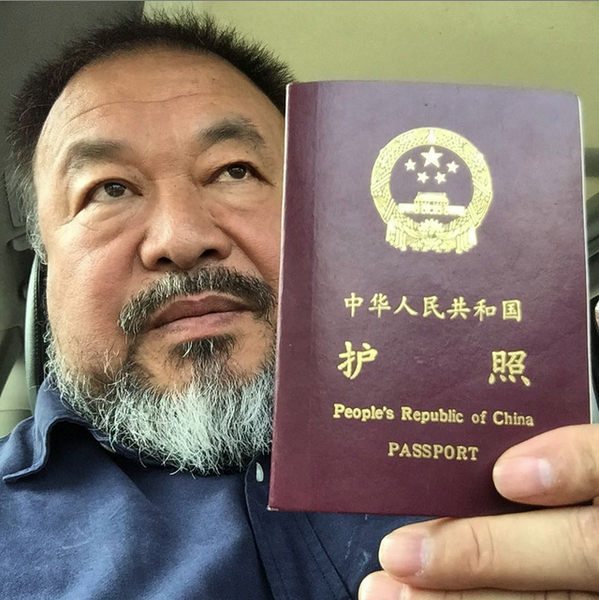

The Chinese authorities have returned Ai Weiwei’s passport, some four years after it was confiscated and he was denied all foreign travel. This news is hugely welcome, whatever one thinks of Ai’s art. (The first response to our Tweet the news this morning: ‘Stop praising this fool please. Seriously’). No individual should be denied the freedom of movement on the basis of their political beliefs, and no public figure should ever face the farcical, state-driven harassment against which Ai has continued to work and speak.

It now looks like a coup for the Royal Academy to be hosting a vast retrospective this autumn – presumably one of the first displays of his work that the artist will now be able to visit outside China. I wonder whether the RA has itself pitched in with some soft diplomatic encouragement. The institution has, after all, partnered with art schools in Beijing and Hong Kong in the last 12 months, establishing an artist-in-residence exchange programme, and it has run curatorial exchange programmes with museums in Hong Kong.

What will be interesting, come September, is whether Ai’s new freedom to travel affects how his work is presented – and whether future installations will take a different tone from his recent output. For in a sense, Ai has become a digital artist over the last four years, communicating with curators, gallerists and journalists via Skype, and speaking to a wider public through Twitter and Instagram. ‘The Internet lets me travel,’ he told Sarah Thornton via Skype in her 33 Artists in 3 Acts (though, as she noted, ‘his image is pixelated and his voice is occasionally garbled’). Will the RA exhibition, and other shows to come, feel more intimate, more direct and less ‘pixelated’, for not being prepared down fibre-optic cables?