Some achieve distinction in one or possibly two branches of the world of art, but few, if any, are outstanding in all of them. Alan Bowness – art historian, curator and museum director, critic and journalist, and a collector himself – was just such a man, for all his personal modesty and quiet public profile. What drove him was his love for, and thirst for knowledge of, 19th- and 20th-century art – painting and sculpture especially. This allowed him to become one of the most effective proselytisers for contemporary art, which in Alan’s heyday was very much a minority, and some would say elitist interest. (As an educator, he no doubt thought that every individual, with self-willed effort, might join in the pleasures that all the arts bring.)

Alan was first exposed to the worlds of Picasso and Matisse in the years just after the Second World War. In 1946, as an 18-year-old boy, he visited a highly influential exhibition of paintings by the two artists at the V&A – a symbol of a reopening world. A lifelong Quaker and at this time a conscientious objector, he chose to do national service with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit and the Friends’ Service Council in England, Germany and Lebanon, before beginning his studies in modern languages (French and German) at the University of Cambridge in 1950. It was here that he discovered the art holdings of the more or less deserted Fitzwilliam Museum – so deserted that he made friends with the director, Carl Winter, who was glad to notice a frequent and studious visitor.

He graduated from modern languages to art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art, and further to art criticism for a number of journals. His inquisitiveness led him to trawl around the London art galleries of the ’50s and early ’60s. These were the worlds of the Fine Art Society, of Helen Lessore and her Beaux Arts Gallery, and of John Kasmin and Robert Frazer’s eponymous West End spaces, where they brought new American and British art to public attention. Bowness’s personal sympathies, however, were less with figures such as Francis Bacon or, later, David Hockney, even if he perceived their strengths. He rather preferred immediate post-war British figuration – John Craxton (regarded by some in his time as a kind of British Picasso); the ‘Two Roberts’, Colquhoun and McBride; and Keith Vaughan. Other favoured artists of these generations, about whom he wrote admiring monographs, included above all Henry Moore, and then Ivon Hitchens, Victor Pasmore, Alan Davie, Ceri Richards and William Scott.

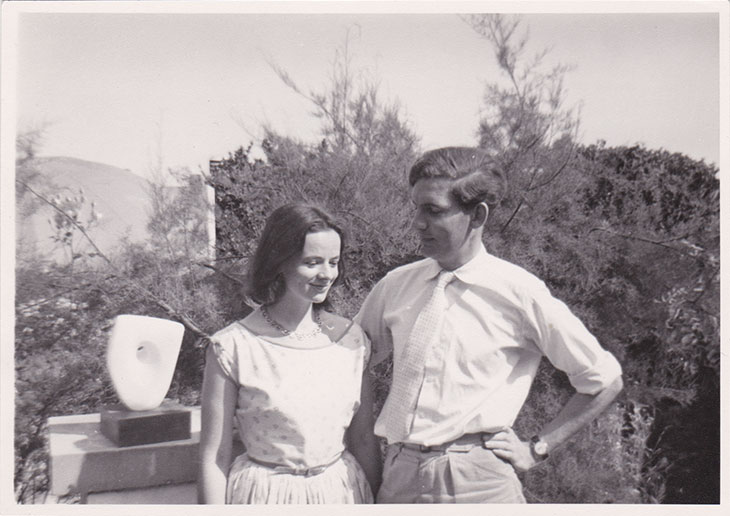

Alan Bowness with Sarah Hepworth-Nicholson in Barbara Hepworth’s garden, Trewyn Studio, St Ives (c. 1958)

Alan was to become even more engaged with the work of two great generations of British artists based largely around St Ives in Cornwall. These of course included Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson (whose daughter, Sarah, Alan was to marry in 1957). But also there were Patrick Heron, Peter Lanyon, Roger Hilton, Terry Frost, Bryan Wynter and a host of others. Alan wrote on all of these figures; they were all to become friends as he and Sarah put down roots in St Ives as well. As I recall, from my one visit to St Ives to stay with them, every morning Alan in his very old-fashioned dark grey flannel swimming trunks would go for a bracing cold swim – after which, during my visit, he took me to meet Patrick Heron at his Eagles Nest studio, the émigré Cornish artist painter Karl Weschke, and others.

Alan Bowness had first entered my life, without knowing it of course, when as a 19-year-old university student I visited that seminal show at the Tate, ‘Painting & Sculpture of a Decade 54–64’. The exhibition, which he co-curated with Lawrence Gowing and Philip James, was life-changing for me, and I believe for many others of my age. For someone who was studying general history rather than art history and had always been more comfortable with Old Masters and classic modernism, the exhibition came as a revelation of the contemporary. I remember its astonishing and calculated presentation of British, other European and above all American painting and sculpture. Picasso and Max Ernst were then still alive and active, but it was artists like Mark Rothko, Anthony Caro, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg who were now making the big waves, as well as local bad boys such as David Hockney and Allen Jones. Some 350 works were all shown in an intense, labyrinthine installation designed by Alison and Peter Smithson in the Duveen halls of the Tate Gallery at Millbank.

Alan Bowness (left) with Alison Smithson and Philip James during the installation of ‘Painting & Sculpture of a Decade 54–64’ at the Tate Gallery, London, 1964. Courtesy Smithson Archive © Smithson Family Collection.

Much later, when I arrived at the Royal Academy as its Exhibition Secretary in 1977, the Arts Council was organising there, with Alan as the British curator, the magnificent Gustave Courbet exhibition that had come from Paris. Two years later, this time in his role as Professor of Art History at the Courtauld, he co-organised ‘Post-Impressionism’, an exhibition that was transformative for the RA’s reputation and which was lead-curated by two of his most distinguished students, John House and MaryAnne Stevens. The show was intended as a celebration of what then was known as the ‘New Art History’, which was rightly attempting to break down that linear story describing the advance of modern art from Impressionism to abstraction. As well as pushing the old Roger Fry favourites – Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh et al – the exhibition made the case for their forgotten Parisian Symbolist and Naturalist ‘broadbrush’ contemporaries: the likes of Puvis de Chavannes and Bastien-Lepage, and their European contemporaries. It was this new approach that was adopted by the Musée d’Orsay, then being set up in Paris. I well remember the Orsay’s founding director Michel Laclotte and around ten of his colleagues, many to become great luminaries of the Parisian art world, coming to see the show en bloc. All of us then, Alan included, were to take over a restaurant in Chinatown in London, where we debated the merits of these new values. As I recall, Alan himself – always with his knowing, gentle smile – was equivocal on the question of whether these ‘new’ discoveries were ultimately a match for the true Impressionists.

In 1980 Alan was finally to become director of the Tate Gallery, the position he held with distinction until 1988, making great acquisitions, especially in the more or less disregarded field in the UK of German art: Kirchner, Beckmann, Grosz and Beuys, Baselitz, Kiefer. In 1984, he also famously founded the Turner Prize, whose first recipient was the painter Malcolm Morley. Three years earlier, in 1981, I had put together, with Nicholas Serota and Christos Joachimides at the Royal Academy, the exhibition ‘A New Spirit in Painting’. Charles Saatchi, the omnivorous collector, was already a huge presence on the international art scene, and was investing heavily in many of the young artists included in the RA show. I remember Alan telling me that the Tate need not purchase work by these artists, whom he indeed believed to be significant – it would ultimately be given to the museum by Charles. Of course, things didn’t work out so smoothly – but the tangled story of the misunderstandings between Saatchi and the Tate is one for another time.

Nonetheless, under Alan’s aegis, great works – such as Picasso’s Weeping Woman, which had belonged to Roland Penrose – found their way to Millbank. During Alan’s relatively short tenure of eight years, the Clore Gallery came about, and plans for the Tate Liverpool and St Ives were instigated. All these developments were of huge significance, paving the way for the vast expansion of Tate’s reach across the UK, realised during the tenure of Alan’s successor, Nicholas Serota.

After his retirement Alan became the director of the Henry Moore Foundation, and he naturally found more time to devote himself to the legacy of Barbara Hepworth. In recent years we met mostly at concerts – he and Sarah were devotees of classical music and serious contemporary music too: composers like Peter Maxwell Davis, Harrison Birtwistle, Thomas Ades, and many more British composers were central to their interests. They were regulars at all the London music venues, most especially the Wigmore Hall.

Alan Bowness was a true man of ‘high culture’ – perhaps not the most fashionable thing nowadays. When Henry Moore died in 1986, I remember listening by chance to Alan on BBC radio’s Today programme on which, as I recall, he described Moore as ‘Probably the greatest sculptor since Michelangelo’ – a simple statement that, whether ‘true’ or not, hints at the genuine and quite particular passions of a man with a nonetheless rich and varied career.

Norman Rosenthal was Exhibitions Secretary at the Royal Academy of Arts from 1977 until 2008.