From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unless you’re a family member or a psychotherapist, you rarely get to rifle through someone’s childhood memories and personal touchstones, but while visiting Alex Da Corte at his North Philadelphia studio, it feels like I am doing just that. The Venezuelan-American artist is putting together the final touches on a set of vitrines for his show ‘The Whale’, at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (2 March–7 September). These will hold objects that give insight into the artist’s practice, as well as the references – from comic books and dollar-store toys to family photos and magazine covers – that feed into the finished works, in this case mainly paintings. ‘I’ve pulled all of this archival paper material that’s never seen the light of day to put together a sampling of what it looks like to get to the painting,’ Da Corte says.

His CD Paintings, for example, developed from his early use of plastic compact disc cases as palettes for mixing paint. As the paint dried into peelable sheets, he realised it could serve to mask off specific images on the liner notes, such as Janet Jackson’s stunning smile or Mariah Carey’s rainbow-splashed bust, as seen in the paintings Siren (After E K Charter) (2015) and The End (2017). (Music has always been and continues to be a deep well for Da Corte, who recently collaborated with both St. Vincent and Kim Deal on music videos.) The CD works also led to Da Corte’s more recent reverse-glass paintings, which employ a technique often found in sign-making and hard-drawn animation, in which an image is painted on the ‘back’ of a sheet of clear glass or plastic, so that when viewed from the ‘front’, the first layer is the topmost.

The End (2017), Alex Da Corte. Courtesy Alex Da Corte Studio; © the artist

Other items are much more personal. A drawing made by his mother features cartoony portraits of her family on one side and a dancing pumpkin-headed character on the other, proof that Da Corte came by his love of Halloween and dressing up in costume honestly. A photograph shows Da Corte’s teenage bedroom in New Jersey, across the walls of which he painted a cavalcade of Disney villains, from Ursula and Cruella de Vil to Jafar and Scar, all impressively rendered mid-scowl or flounce. ‘It was the first time I was able to translate something from a small scale to a large scale with no projection. And I realised I could [do that] just by eye,’ Da Corte says.

These were the early steps Da Corte took towards becoming an artist, although at the time he thought it would be as a Disney animator, creating the characters he loved so much. It was also an early lesson in how a person shapes their identity through the images and stories they connect to, and how that evolves throughout one’s life. ‘I was so absolutely into the villains. And it makes sense, since so many of the people who were illustrating those Disney villains, classically, were queer,’ he says. ‘I didn’t know that at the time, as a young person, but they have a certain sass, and there’s a certain kind of rhythm to them and their body language – in retrospect, it’s all so camp.’

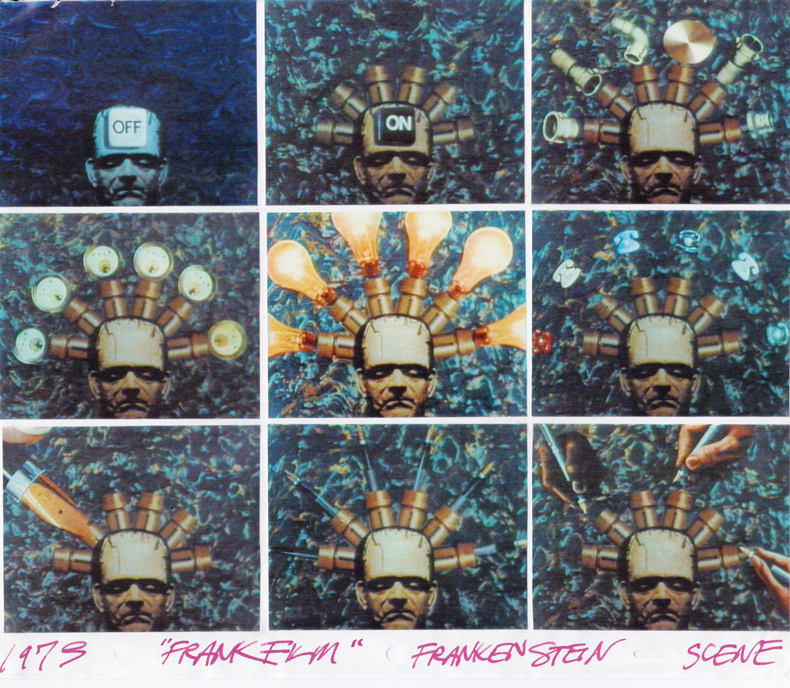

Another pivotal point came when Da Corte was studying animation at the School of Visual Arts in New York, when his teacher Howard Beckerman showed him the Oscar-winning short Frank Film, by husband-and-wife directors Frank and Caroline Mouris. They collected thousands of images cut from magazines to create an audio-visual collage of the things Frank enjoyed throughout his life, a kaleidoscopic dance against a soundtrack of Frank narrating his life story while simultaneously running through a list of words that start with the letter F.

Still from Frank Film, 1973, directed by Frank and Caroline Mouris. Courtesy and © the artists

‘It was the first time I ever heard the word avant-garde,’ Da Corte says. ‘I didn’t know anything about art. And what was so cool about it was, it was this guy, in this kind of unremarkable way, talking about the things he loved and sharing what he liked. And it gave me this licence to say, “Oh, well, I can make work about the things that I like, and if I like ketchup, say, which I do very much, I can make work about that, and that’s also okay.” It just broke my brain open.’ When Da Corte went home after that class, he immediately wrote Frank Mouris a letter, and the director responded, sending a VHS copy of the film, which Da Corte has kept for more than two decades and plans to include in his show at the Modern. (He also furthered his art historical education soon after this experience, completing a BFA in printmaking and fine art at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, and an MFA at Yale.)

When asked what makes him decide to keep one object over another, Da Corte points to a patch of green plaid, explaining it is the pocket of a long-lost favourite shirt, while a pair of teddy bear decals create an association with Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s depictions of love. ‘I thought it was extremely cute in the moment – this probably could have been 25 years ago, but there it is, and then it stays with me,’ Da Corte says.

All these objects are keys to unlocking the complex relationships embedded in the work Da Corte has produced over the past 20 years, which draw equally on pop culture and art history, consumerism and creativity, humour and pathos. To further expand on this psychological mining, the whole exhibition at the Modern is modelled around Carl Jung’s concept of a mythological ‘night sea journey’, in which a hero is devoured by a sea monster and dragged through the depths to commune with the ghosts of their past, before rising again as a new person. The first thing visitors will see when they enter the galleries is a new work, an image of a big, black anvil, pulled from the cover of a Baby Huey comic book and recreated in puffy neoprene, looming large on a wall painted blue like a hovering whale tail about to crash against the sea. ‘It’s some kind of large vastness that’s always on the horizon,’ Da Corte says. ‘It could be death, it could be opportunity – it’s just the future. It’s the thing that exists that’s further than us or our understanding of what is next.’

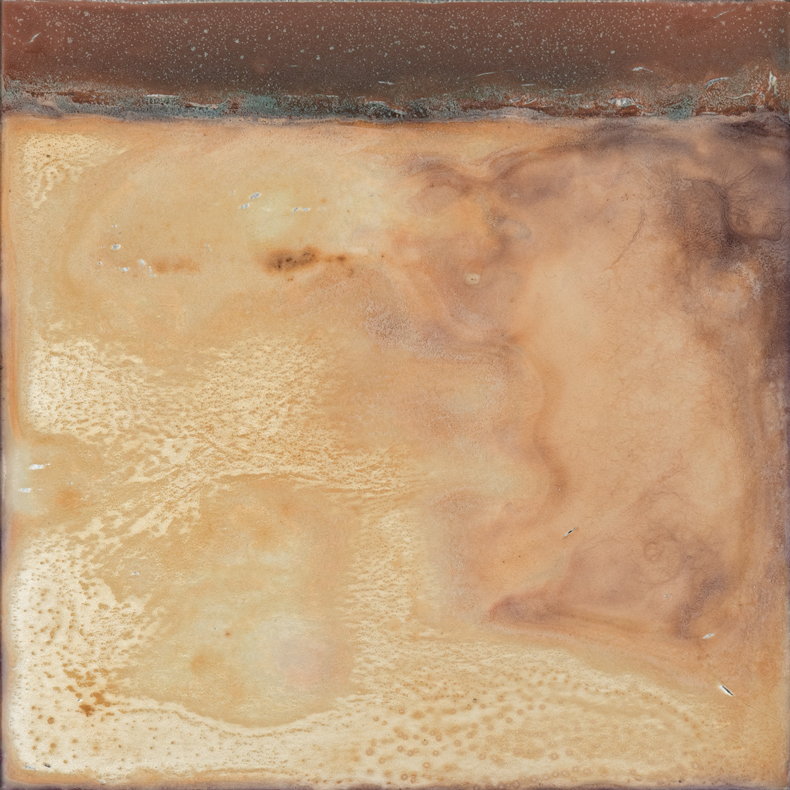

Facing the anvil is a small painting hanging on an opposite wall, Andromeda (2012), the earliest work in the show and an example of Da Corte’s experiments using store-bought shampoo. Condensed and poured onto a framed mirror and allowed to dry, the shampoo has morphed over the years, darkening from a brilliant gold and blue to an earthier brown and grey, growing a soapy crust, and seeping into the surrounding frame.

Andromeda (2012), Alex Da Corte. Photo: Neighbouring States; courtesy Alex Da Corte Studio; © the artist

‘It bleeds and it changes, and it’s very much alive,’ Da Corte says of the work, adding that each shampoo painting is completely unique in how it has aged. ‘The ones that I made for my parents, around the same time, are in perfect condition – but you could put one somewhere else, and it might become completely volatile and change, and you just don’t know, which is part of my attraction to it.’ Da Corte is so invested in how the painting might change that he is personally driving it to Fort Worth, along with the archival materials that will fill the table-top vitrines, undertaking his own ‘night sea journey’ with the pieces of his past.

This constant exploration of personal psychology, and what the things we love say about us and our relationship with the world, is the core of Da Corte’s work. It plays out even more theatrically in his films and immersive installations, in which Da Corte takes a starring role, enacting beloved characters from his childhood, such as Mister Rogers, Frankenstein’s monster, the Wicked Witch of the West and Popeye, to name just a few. (His new studio in the former Frankford Arsenal, which he just bought and moved in to last June, was fittingly once used by the Opera Company of Philadelphia for set building and storage.)

Installation view of Rubber Pencil Devil (2018) by Alex Da Corte in ‘For a Dreamer of Houses’, at the Dallas Museum of Art in 2021. Photo: John Smith; courtesy Alex Da Corte Studio; © the artist

One of Da Corte’s best-known film installations, Rubber Pencil Devil, originally created for the 2018 Carnegie International exhibition in Pittsburgh, features 57 vignettes, in which Da Corte performs as different characters, including the titular scarlet-skinned devil, who in one scene is a weatherman predicting a spate of fires across the country. The nearly three-hour-long work was shown at the 2020 Venice Biennial and is currently on view in the show ‘Ear Worm’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto (until 3 August). A new iteration, Rubber Pencil Devil (Hell House) (2022) screening inside a neon structure that appears to be on fire, was commissioned by the Glenstone private museum in Washington, D.C., and can be seen there from 20 March.

The Glenstone show has given Da Corte the opportunity to document the work more thoroughly – ‘I’m quite an avid bookmaker,’ he says – and the more than 700 props and costumes that went into making it. It also led to the creation of a new billboard project for the High Line in New York, due to go on view this spring, for which Da Corte once again donned his Pink Panther costume from the film. This time, the character will be seen lounging on the ground, with an array of blank protest placards surrounding him. ‘I thought pink is the kind of righteous colour to work through for this year. I had just written this essay on softness and soft power, and I was thinking about memory loss, about people who have dementia, and how there’s a kind of softening that happens. But how can we rethink softness as something that is powerful?’ Da Corte says.

One example Da Corte came up with is the difference between falling and lying down, how one is an action without true autonomy, and the other is a choice. Similarly, the blank placards draw on ‘the need to find a voice, to speak to the many things that we want’ during difficult times and ‘not knowing how to’, Da Corte says, because there are too many words to choose from, or because none of them will do. ‘Silence has its own kind of power.’

Still from Rubber Pencil Devil by Alex Da Corte, a set of 57 vignettes in which the artist performs as different characters. Courtesy Alex Da Corte Studio; © the artist

The project also connects to other recurring themes in Da Corte’s work, such as a person’s relationship with their own body and how this affects their perception of themselves, especially over time. ‘You can spend a whole lifetime reckoning with that,’ he says, ‘the person you thought you were going to be, or what was foretold you might be and you aren’t, and how that can be completely horrifying and devastating and alienating – and maybe, for some, gratifying.’

This kind of evolution, as Da Corte sees it, can apply just as much to objects as it does to people, since objects have a life of their own and in many ways are extensions of the people who make them, or use them, or appreciate them. ‘I’ve always likened this kind of shifting to the moment when a regular t-shirt that you bought at a store becomes your favourite t-shirt,’ he says. ‘There’s no way of knowing when that was, but all of a sudden it happened.’ This humanising of things might be why Da Corte has an issue with terms like ‘ready-made’ and ‘found object’ when it is applied to items that were imagined, designed and constructed by people, even if forgotten or ignored.

‘Things have meaning because they’re made by people,’ he says, adding later on that ‘there’s so much invisible labour around the world.’ He gives as an example the painting of a home’s exterior or a gallery’s walls, usually done by a hired professional who isn’t given a second thought once the work is done. The subject is a personal one for Da Corte, who comes from a family of house painters, including his brother Americo, who has collaborated on previous projects with the artist. Among them is his installation ROY G BIV for the 2022 Whitney Biennial, for which Americo painted the exterior a new colour of the rainbow every few weeks. Drawing attention to the work that goes in to something as deceptively simple as the colour of a surface turns it into ‘a kind of force with changing moods and a psychological impact over time’.

Part of Alex Da Corte’s installation at the 2022 Whitney Biennial, ROY G BIV, which also involved his brother Americo painting and repainting the outside walls in different colours. Courtesy Alex Da Corte Studio; © the artist

Throughout our conversation, we keep returning to the archival objects that have informed Da Corte’s work for so many years. Like Jung’s hero, we gather the elements of the past in order to shape the form of our future. Sometimes this means dealing with genuinely painful memories, as well as joy, a familiar experience for Da Corte, who has weathered ‘unimaginable violence’ to his body because of multiple surgeries he needed when he was young and the Crohn’s disease he lives with now. ‘It sort of sets you in this place where you have a choice,’ he says, remembering a time when his struggles with his health left him weeping and his mother shook him and told him, ‘You have to choose to get through this.’

‘So yes, you absolutely have to go through the depths,’ Da Corte says. ‘Absolutely go right through it and be in it, accept it, whatever that thing might be, and find some kind of betterment, or new perspective.’ Returning to process the pain of the past can also teach a person valuable lessons about accepting the flaws and failures inherent in growth. ‘For me to survey all that I have done in these many years is not to propose that this is all wrapped up in a beautiful bow, but that it is an unravelled kind of mess on a table, and that too, is righteous.’ But perhaps the biggest lesson Da Corte says he’s learned from this constant psychological digging is to live with empathy. ‘That’s something that I truly work towards and want to be,’ he says. ‘And I think all of my projects are about that.’

‘Alex da Corte: The Whale’ is at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth from 2 March– 7 September; recent works by Alex da Corte will be at Glenstone, Potomac, from 20 March.

From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.