On my way to see ‘Safety Curtain’ at Auto Italia in Bethnal Green, I passed a wall of Just Stop Oil posters. Someone had torn the bottom of each one; the rips looked like grabbing hands, which is fitting, given that the climate activist group is known for targeting famous artworks.

Actions by activists to effect political change have been on the rise this century, matched by a proliferation of exhibitions of politically engaged art. These have included ‘The Horror Show’ at Somerset House in 2022, which exhibited some of the country’s ‘most provocative artists’, to ‘Women in Revolt’ at Tate Britain in 2023, and ‘Re/Sisters’ and ‘Unravel’ at the Barbican in 2023 and 2024 respectively. In a few weeks, ‘Here is a Gale Warning: Art, Crisis & Survival’, will open at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge.

Installation view of Cancelled Performance (2025) by Alex Margo Arden, on the outside wall of Auto Italia, London. Photo: Jack Elliot Edwards; courtesy the artist/Auto Italia; © the artist

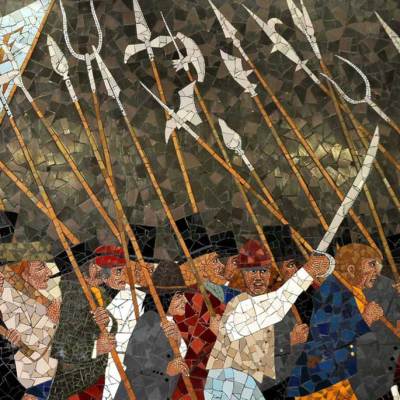

‘Safety Curtain’ does something different. Spread across two rooms, it is an exhibition of photographs, installations and paintings by Alex Margo Arden, in which the ‘evidence’ of recent actions is reinstated into painted copies. Her first exhibit is pasted on to the vitrine outside the gallery, a reproduction of posters advertising Les Misérables, plastered with stickers telling us that ‘Tonight’s performance is cancelled due to circumstances beyond our control’. The display refers to a performance in London in 2023 that was interrupted by climate activists during the musical’s protest song ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’ Prints showing reconstructions of the safety curtain for Les Mis are exhibited inside (Barricade); the curtain has been painted with the set of the rebels’ barricade and hung in situ at several London theatres. The glass protecting a painting in a gallery is also a safety curtain. Both separate the audience and viewers from the artwork.

Inside Auto Italia’s first room are recreations of nine masterpieces, showing the splats, splotches, dribbles, smashes and cracks inflicted on them by climate activists between 2022 and 2024. Each canvas is described as a ‘scene’, with details of when and where the attack took place – a painted reconstruction of the crime. To make the works, Arden sourced digital images online and sent them to a reproduction studio to transfer into paint on canvas.

Scene [6 November 2023; National Gallery, London] (2024), Alex Margo Arden. Courtesy the artist/Auto Italia; © the artist

The works include Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus, which was targeted with a safety hammer in the National Gallery in 2023, and the Mona Lisa, which in 2022 was pelted with cream cake. In the case of the former, the activists were repeating the action of the suffragette Mary Richardson, who in 1914 used a meat cleaver to slash the canvas in protest at the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst. The blows delivered in 2023 have been painted back on to a replica, a constellation of nine pressure points and fissures. When it comes to the Mona Lisa, Arden has recreated both the action and the reaction in triptych form: the smearing of cream cake over the bullet-proof glass in the first canvas and its removal through panicked wiping by gallery staff in the second and third. Unlike at the National Gallery or the Louvre, the visitor here is able to get up close and absorb these ephemeral effects reproduced on unglazed canvases.

In a recent interview published in Elephant magazine, Arden stated that she is ‘less interested in the object as it comes out of the artist’s studio in 1887 than the object as something that’s been in the world since then’ and argued that institutions rarely acknowledge the activism their artworks have been subjected to. What form might that acknowledgement take? In 2013, Tate Britain mounted ‘Art Under Attack’, an exhibition that examined 500 years of iconoclasm in the UK, from the breaking of religious images during the Reformation to throwing paint-stripper at a sexist sculpture in the 1980s.

Scene [14 October 2022; National Gallery, London] (2024), Alex Margo Arden. Courtesy the artist/Auto Italia; © the artist

Last year, restorers at the Rijksmuseum began removing the varnish from Rembrandt’s masterpiece The Night Watch (1642) in preparation for the application of a new coat. The painting has been vandalised three times, twice by knife in 1911 and 1975, and once by an acid attack in 1990; in the last of these instances, the varnish was damaged but ultimately helped protect the painting from serious harm. Now eight restorers work in a specially constructed glass chamber in full public view. Promoted as ‘Operation Nightwatch’, their ‘detective work’ includes uncovering both the conservation history of the painting and the acts of malice directed against it. The transparency of this process, enacted in a slow gestural performance, testifies to the picture’s history and vulnerability.

The ethics of restoration (returning an artefact to its original state) and conservation (preserving the artefact in its current condition) are constantly evolving, aided by new techniques and technologies. Decisions have to be made about retaining signs of damage or correcting mistakes subsequently added to an artwork. Sometimes, an act of violence becomes part of the object’s story. One such example is the statue of the merchant slave-trader Edward Colston, which in 2020 was toppled off its plinth, daubed with red and blue paint and pushed into Bristol Harbour by anti-racism protesters. It was subsequently retrieved and exhibited – horizontally, with graffiti intact – in a glass case at the M Shed Museum, accompanied by a carefully worded gallery card.

The toppled and graffitied statue of Edward Colston on display at the M Shed museum in Bristol. Photo: Polly Thomas via Getty Images

Public museums and galleries cannot ignore the possibility of attacks. In 1914, gallery directors requested bags, muffs and umbrellas to be left at the entrance and even discussed banning women from their institutions altogether. Today, the situation is more complex. Organisations find themselves caught between policies aimed at inclusivity, openness and access on the one hand (and on which their public funding depends) and their duty of care for both staff and their collections on the other.

Tate Modern has tried to address the challenge of climate change by appointing an ecology curator and using rainwater in its toilets. Meanwhile, at the National Gallery, liquids and large bags are not permitted in the building. ‘More of our pictures are glazed now, including several hundred more added in the past 18 months or so,’ the museum’s director, Gabriele Finaldi, told the Art Newspaper in 2024. In fact, more glazing also means more potential targets, as climate activists tend to cause ‘symbolic damage’ to paintings under glass and real damage to the frames.

In its response to the sudden shock of protest actions on artworks held in our cultural institutions, ‘Safety Curtain’ has a sense of immediacy. While the climate crisis is the main spur for these protests at the moment, it is worth remembering that Tate Britain’s ‘Art Under Attack’, which took place just over a decade ago, did not feature any climate activists – a fact that demonstrates just how quickly concerns can change. But Backstage Campaign, the final work in the exhibition, is an installation of five packing crates from the Royal Academy that once contained plaster casts of classical busts used for teaching. These were defaced during protests in the 1960s by students who felt that this form of pedagogy was outdated; now the crates are filled with old stepladders and brooms. Through this exhibition, Arden responds to a contemporary moment while also demonstrating that sociopolitical fracture – and the activism that results from it – have a much longer history.

Installation view of the three versions of Scene [29 May 2022; Louvre, Paris] (2024) by Alex Margo Arden at Auto Italia, London. Photo: Jack Elliot Edwards; courtesy the artist/Auto Italia; © the artist