From the May 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Anselm Kiefer is the master, both literally and figuratively, of laying it on thick. Remarkably steady in both his interests and his methods from the late 1960s through to the present, Kiefer has been approaching an artistic achievement that is unique. Now entering his ninth decade, he has arrived at the reliable production – the perfection, even – of profundity in the almost total absence of subtlety. If this sounds like an insult, it isn’t one: as these two exhibitions covering different periods of his career show, Kiefer’s depths may be all surface, but his surfaces are all depths too.

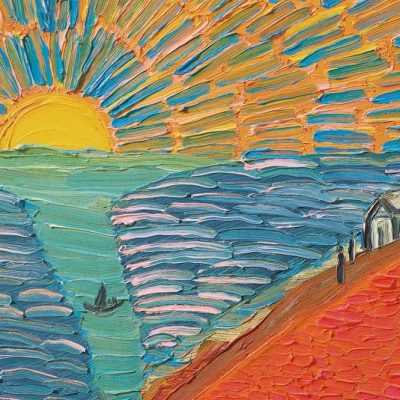

The centrepiece of the Amsterdam show, which is hosted jointly by the Van Gogh Museum and the Stedelijk, is Where Have All the Flowers Gone (2024), a work that shows Kiefer in monumental overdrive: symbol engines set to maximum; reference torpedoes armed and away. Heaven and Earth, the five vast canvases shimmer at their heights with gold, darkening to rust, charcoal and verdigris below. Above, a disconnected frieze of female figures strike poses ranging from a yogic forward fold to the convulsions of a psychiatric patient; below, rows of encrusted overalls – headless, handless, footless figures, marching out of the canvas towards the viewer. At intervals, cascades of dried rose petals flutter and descend, here trapped in the paint, here pooling on the floor to be trodden on by viewers. At the summit, in Kiefer’s trademark polite schoolboy hand, are the German lyrics to Pete Seeger’s anti-war anthem ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone?’ (1955), as sung by Marlene Dietrich. In the central end panel is one of Kiefer’s favourite leitmotifs: a sapling rising from the belly of a corpse. Portrait heads of pre-Socratic philosophers prod the viewer in the direction of Kiefer’s inspiration: the Heraclitean panta rhei (everything flows).

Where Have All the Flowers Gone (2024; detail), Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Nina Slavcheva; courtesy the artist/White Cube; © the artist

It is all, as they say, on the nose. This is a world in which flowers are picked and petals fall and everything progresses to the grave, and from the grave in turn bloom the flowers that will be picked and… The roses nod to Elagabalus smothering his banqueters; only here it is the viewer, powerless as meaning descends on them in great crushing billows. It is as if Dietrich’s three minutes of guitar and syrupy strings had been re-orchestrated – to brilliant effect – by the ghost of Wagner.

There are times, though, when the maximalism is less successful and not all the recent works in Amsterdam hit the mark – particularly in the Van Gogh Museum. Despite exploring a relationship that has marked Kiefer’s output since he was a schoolboy – to the extent of retracing Van Gogh’s footsteps with his own sketchbook in 1963 – the pairing seems better on the page than in the gallery. While Kiefer’s direct and sensitive catalogue essay on Van Gogh’s defiance is a gem, as are the sketches from 1963, the massive homages The Starry Night (2019) and The Crows (2019) fall flat against the diminutive Van Goghs opposite. Despite the quality of the works from 1970–90 in the Stedelijk’s section of the show – with a rare chance to see the hypnotic film Poland is Not Yet Lost… (1989) – the curation feels unfocused; a paean to star power rather than to the art itself.

Wald (Forest) (1973–74), Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Adam Reich; courtesy Hall Art Foundation; © Anselm Kiefer

The contrast with the approach at the Ashmolean is sharp. What ‘Anselm Kiefer: Early Works’ lacks in scale, it more than makes up for in both the quality of the works and the acuity of the curation by Lena Fritsch. Focusing on the period 1969–82, the show draws heavily on works from the Hall Art Foundation’s extensive Kiefer collection, many of which originally belonged to Georg Baselitz and were acquired from Kiefer at the time of their production. As a record of his development as an artist, that collection is unequalled and comes to life especially well under Fritsch’s curation. Above all, the Ashmolean does a superb job of unpacking Kiefer’s references – a knotty weave of literature and myth and history mapped on to the contours of the European landscape. The works here show an artist who, while remaining essentially unchanged in his concerns throughout his career, arrived at his current pomp through restless experimentation and introspection. Profundity is matched here, if not by subtlety, then often by delicacy.

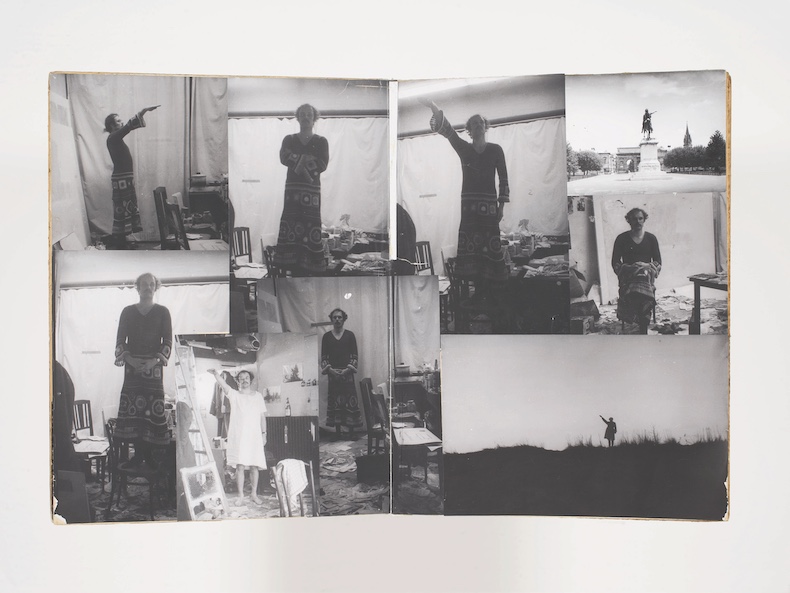

That delicacy was not always obvious. Just six years after the 18-year-old Kiefer had set out to sketch the descendants of Van Gogh’s peasants, he had completed his transformation into an artistic and political radical, confronting the legacy of Nazism. He captures himself again and again, on camera and in paint, undertaking the Occupations (1969), in which he threw out Nazi salutes at key locations in Germany, dressed in his father’s Wehrmacht uniform. A life-sized self-portrait from 1970, though, recreates the pose in introspective mode: in lightly washed acrylic and charcoal, Kiefer’s eyes peer out from behind glasses as if looking into a mirror in an attempt to make out what on earth he looks like. Despite the violence of the gesture, the piece is Romantic, with a capital R: the artist trying to look into his own soul and see what’s really there.

For Jean Genet (1969), Anselm Kiefer. Courtesy Hall Art Foundation; © Anselm Kiefer

That capital R is joined to a lowercase one in Ich – Du (I – You, 1971), a group of small landscape oils inscribed with the names of his wife and new son. At the centre, two trees grow together in an early-morning mist, each labelled with its pronoun: a smaller, darker ich blending into the branches, the larger, lighter Du floating above. It is easily as eloquent as anything that has come since and, in its way, just as unsubtle, but it shows the young Kiefer capable of a kind of small-scale beauty you could hardly suspect was possible looking at his later imperial phase. We may want, as Kiefer puts it in his own essay on Van Gogh, to ‘talk of Last Things, of death and judgement’, but it is a pleasure to hear him talk of first things as well – love and birth – and in something like a whisper, too.

Anselm Kiefer: Where Have All the Flowers Gone is at the Stedelijk Museum and the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until 9 June.

Anselm Kiefer: Early Works is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, until 15 June.

From the May 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.