I bought a Rembrandt the other day. Just a very small one, since I’m not made of money. A playing-card sized study of an old man’s head in ink and wash, it is almost as Rembrandtian as Rembrandt gets: a miniature expression of his unstinting interest in the ageing face. The real giveaway, though, is the signature neatly inscribed at the bottom left. It’s gauche, I know, to talk about money, but at £300, I suspect I got an absolute bargain. Who knows how much I’ll get when I flip it at Christie’s next month.

One can dream. While the auctioneers charitably listed the work as by a ‘follower’ of Rembrandt, what it really is is a fake – perhaps purposefully designed as such by its artist or created after the fact, by the addition of the signature. Either way someone, somewhere was a chancer and my pseudo-Rembrandt was the result. Were previous sellers complicit, previous owners taken in? I would love to know. I bought it partly because it really is a lovely thing in itself and partly because, as the Courtauld’s temporary display of fakes from its own collection aims to show, few things are as fascinating as fakery.

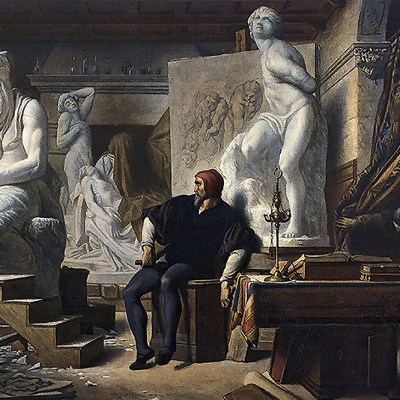

Man asleep in an armchair in the manner of Thomas Rowlandson (n.d.), Eric Hebborn. Courtauld Gallery, London

‘Art and Artifice’ is, it should be noted, a display rather than an exhibition and is probably better thought of as an introduction to the world of artistic forgery than as anything approaching a thesis on the topic. As a primer, it works nicely. With an emphasis on drawings, the curators have assembled a range of works from the Courtauld’s stores to cover more or less the full range of counterfeiting possibilities on offer to the enterprising artistic conman. There are all-out modern-day fakes, as represented by a 1930s pseudo-Dirck van Baburen by Dutch forger Han van Meegeren and a pseudo-Thomas Rowlandson by England’s own prolific Eric Hebborn. Then there are doctored works made out to be more valuable than they are – whether by reworking or the addition of fake provenance. Spurious signatures are a classic, of course, but so too are more elaborate adjustments. A humble drawing reworked to resemble a Rubens, for instance, might have particular pull not least because Rubens was himself fond of reworking other artists’ drawings, apparently for use in his studio. Subtler is the addition of a monogram and blue mount, purporting to show that a drawing had once belonged to the famous 18th-century connoisseur Pierre-Jean Mariette – a significant value booster for the right buyer. If all else fails, authority can be its own fakery. Enterprising 19th-century dealers apparently pressured Constable’s sons to certify works as their father’s, with little regard for the actual hands involved.

The Procuress in the manner of Dirck van Baburen (c. 1930), Han van Meegeren. Courtauld Gallery, London

It is a fascinating selection, offered with deep expertise. And yet, it also feels a little thin. There are some enjoyable philosophical problems to meditate on here – all of which go unraised by the wall texts. If a fake is good enough to convince us, what really disappears when it is exposed? Why should such magic attach to the merest potential scrap of an old master’s output anyway? What, at the end of the day, is value? All fakes are, at root, not so much a creation of forgers as they are a creation of the market. Can the same be said of the great masters’ reputations?

Seascape in the manner of John Constable (n.d.). Courtauld Gallery, London

If would be a lie to say, though, that the interest here is quite so purely intellectual. The joy of all these things – and the shortcoming of this display – is in the stories. Every fake is a narrative layer-cake: from the motives of the fakers, to the gullibility of the buyers, to the detective work of those who finally unmask the deception. Unfortunately, though, the focus of ‘Art and Artifice’ remains stubbornly technical. Those who want to learn about the undisguisable slenderness of machine-made nails, the dating of pigments or the difference between laid paper and wove will have a rare old time – as they should. Others are likely to be left wishing they knew more than the curators seem willing to tell. Without the story of van Meegeren’s unlikely transformation from Nazi collaborator to quasi-folk hero courtesy of selling Göring a fake Vermeer, his van Baburen is little more than an excessively brown pastiche of a minor 17th-century artist. Without the stymied artistic ambitions and stylish unrepentance of its real author, Hebborn’s Rowlandson is just a jolly fat man in a chair. Both, of course, burnished their own legends plenty enough – but then they knew how to give viewers exactly what they wanted.

‘Art and Artifice: Fakes From the Collection’ is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 8 October.