From the October 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

If in English, the genre of memoirs by art dealers probably begins with William Buchanan in 1824, it was another century before the first account was published in French. Pan! Dans l’oeil…ou trente ans dans les coulisses de la peinture contemporaine appeared in 1933, and its author was a woman. At five foot tall, Berthe Weill (1865–1951) was short of stature, but enjoyed an outsized reputation, once being described by Paul Rosenberg – a fellow dealer in the position to know – as ‘the mother of modern art’. Recently translated as Pow! Right in the Eye! (University of Chicago Press), Weill’s autobiography was clearly intended as a provocation. ‘Mlle Weill has a long memory and doesn’t suffer fools gladly,’ one newspaper warned in 1931. In a chronicle of her struggles in the art world over the past three decades, Weill pays tribute to the friendships that sustained her and the artists she loved – while also taking aim at the many who had betrayed and underestimated her. Above all, it exuded her spirit of determination, summed up in her credo: ‘I WILL HANG ON!’

Weill threw herself wholeheartedly into avant-garde Paris, staking her modest resources on the latest experiments of modern art. Unlike some of her more famous rivals, who made fortunes in the process, for Weill art dealing was primarily a labour of love, the satisfactions of which were emotional and intellectual rather than pecuniary. The memoir is an honest account of the constant graft, thrift and creative accounting needed for a small gallery to survive in a marketplace, in which buyers were few, the wider public uncomprehending, and rising stars poached by competitors. The Parisian art world was built on reputation, trust and personal relationships. She raged against Ambroise Vollard, the champion of modernism, for trying to turn Redon and Maillol against her, telling them that she gave away their works for ‘nothing’. Pow! was prefaced with a thinly veiled lampoon against one ‘Dolikhos,’ a dim-witted and pug-nosed dealer who hoarded canvases, bad-mouthed philanthropists such as Isaac de Camondo, and planned to get rich through selling French Impressionism to the United States. For his part, Vollard omitted any mention of Weill in his own, far better known autobiography, Recollections of a Picture Dealer, published three years later – a silence that contributed to the speed with which Weill was forgotten after her death in 1951.

La rue pavoisée (Street Decorated with Flags) (1906), Raoul Dufy. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Photo: Philippe Migeat; Centre Pompidou, MNAM/CCI. dist. Grand Palais RMN

Their feud was typical of her unwillingness to separate her professional and personal attachments. Weill’s activity as a dealer was entwined with her support of left-wing causes, from votes for women to the embrace of foreign artists and refugees. At the height of the Dreyfus Affair she exhibited The Mocking of Zola by Henry de Groux in her shop window, defying the antisemitic prejudices she repeatedly encountered. The memoir is an unusually candid and idiosyncratic document about her guiding principles: ‘I write the way I think,’ she stated unapologetically. The recent English translation by William Rodarmor vividly captures her earthy jokes, folksy wisdom and stinging sarcasm. The notes and appendices to the new edition are also extremely useful in bringing back to life a galaxy of names unfamiliar now, even to specialists. Weill gave a platform to many different art movements, some of which led nowhere, and it’s the candid record of success and failure that makes her account stand out.

Pow! is also indispensable because the archives of the Galerie Weill have all been lost. What we know about Weill’s business is largely due to her own testimony. Her biographer Marianne Le Morvan has been tireless in pulling together scattered additional sources, and pushing for Weill to receive the kind of solo dealer exhibition that has been granted to Vollard. For without his family resources or, frankly, his head for business, it is arguable that Weill was a much more consistent champion of trends in modern art. A new exhibition organised between the Grey Art Museum in New York (where it opens at the beginning of this month), the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris aims to introduce Weill to a wider public. Her career seems especially relevant in light of the growing interest in other early female gallerists (from Katia Granoff and Lucy Krohg to Florine Ebstein Langweil and Jadwiga Zak); like them, Weill can appear both integral and marginal to the Parisian art trade.

Weill’s beginnings were modest. She was born into a Jewish family who had moved from Alsace to Paris after the Franco-Prussian War. Her father was a rag-picker and her mother a seamstress. After a brief period of collaboration, her brother Marcellin decided to give up the art business and get married in 1900, while Weill’s mother deplored her daughter’s refusal to do the same. Weill got her break thanks instead to the two decades she spent working with Salvator Mayer, a relative, who owned a shop on the rue Laffitte (the ‘rue des tableaux’) in the ninth arrondissement, then the main artery of the Paris picture trade. Here she met many of the city’s leading dealers and collectors, including Camondo. After Mayer’s death, it was his widow, Rachel Mayer (née Oppenheim), who was pivotal in helping Weill set up her own shop.

From the outset it was a tough and precarious living. Opened in 1897, Weill’s ‘little cubbyhole’ on rue Victor Massé was cramped, with some canvases secured to a rope using simple clothes pegs. She was obliged to sell things quickly and hence cheaply. ‘Everything had to move,’ she wrote – ‘drawings, engravings, paintings old and modern, miniatures, knick-knacks, everything!’ She relates the bitter story of a superb Degas pastel that she was consigned for just two hours at a price of only 500 francs; she failed to find a buyer, or anyone to lend her the sum, and the picture was returned and later sold by Durand-Ruel for 7,000 francs. Weill’s habit of dutifully noting prices, her belief in ‘the eloquence of figures’, shows the bargains that could still be picked up around 1900: Daumier’s lithographs from Charivari were selling for as little as 10 or 25 centimes, Toulouse-Lautrec was deemed too risqué, and she came across ‘an attractive little Van Gogh for 40 francs’ (which she passed on for 60). In general, sales at the gallery were painfully few, and Weill was obliged to cross-subsidise her trade in modern paintings through a constant influx of new antiques (her ‘salvation’ and ‘real silent business partners’) and later, by stocking rare books, putting her expertise in the art of the 18th century to good use.

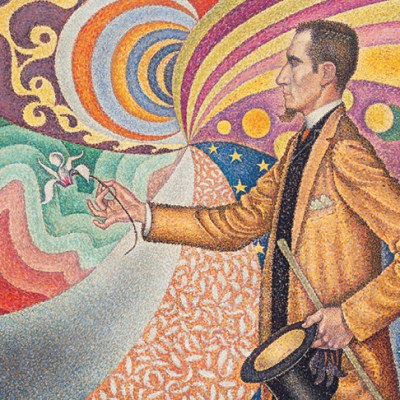

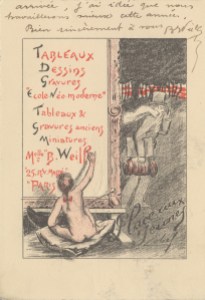

A business card designed for Berthe Weill by Alméry Lobel-Riche in 1901. Photo: Archives Henri Matisse

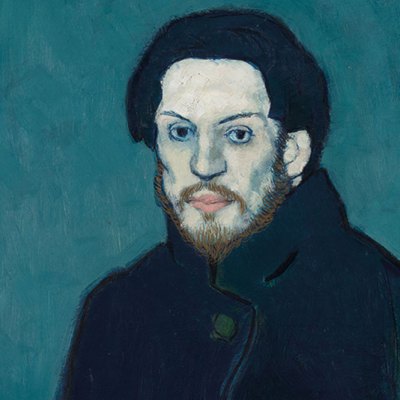

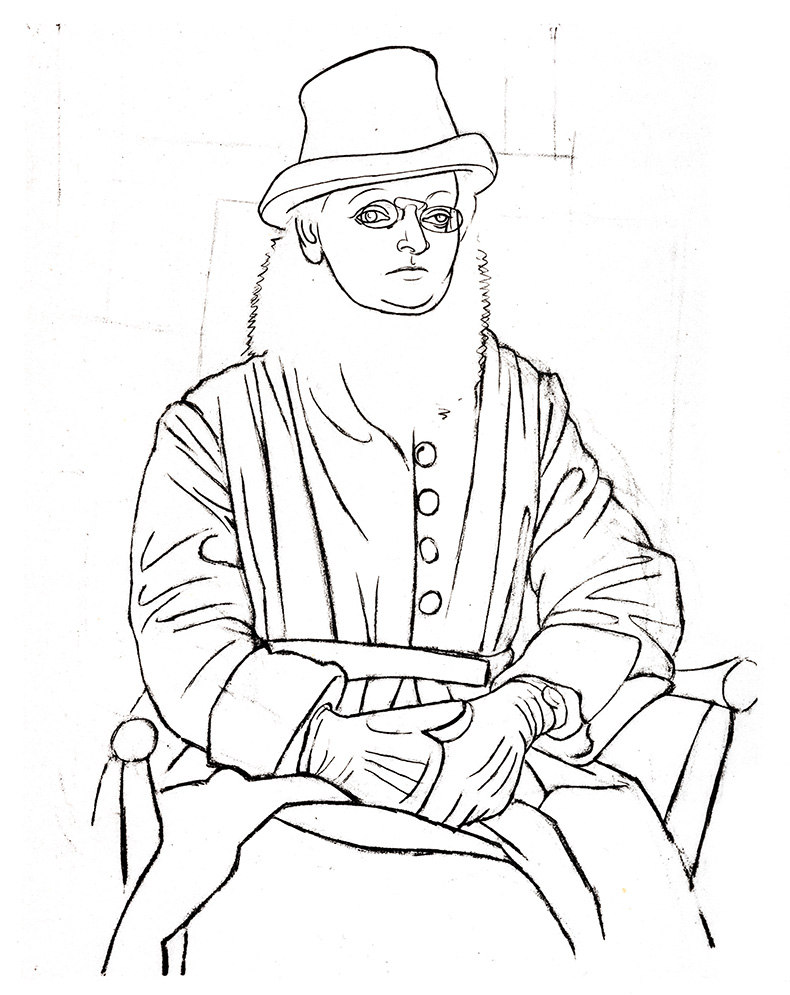

But, as the business card designed for her by Alméry Lobel-Riche around 1900 proclaimed, her real passion was the coming generation; her motto was ‘place aux jeunes’, or ‘make way for the young’. She acted not from calculation, but surrendered to the ‘revolution’ that seemed to be sweeping through the arts, well aware as a sympathetic bystander that she was on a ‘slippery slope’. A crucial contact in the early years was Pedro Mañach, the Catalan entrepreneur who introduced her to his cohort of Spanish painters keen to make a name for themselves at the time of the 1900 Paris Exposition. This was how Weill came to obtain for Picasso his first sales in the city – three pastels of bullfighting scenes, which she bought for a total of 100 francs and sold on to publisher Adolphe Brisson for 150. Weill was always proud of her role in launching Picasso’s career and reproduced the line-drawing he made of her in 1920, seated in hat and fur collar, for the frontispiece of the memoir (see cover). In a repeated pattern, he was soon signed by a rival, wealthier gallery (in this case, Clovis Sagot), and started fetching prices far beyond her means.

Portrait of Berthe Weill (1920), Pablo Picasso. © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2024

Le Morvan describes Weill as an ‘anti-commercial’ dealer, building her relationships with artists on admiration and affection, rather than any certainty of profit; in contrast to gallerists who would expect a fee in exchange for showing an artist’s work, she offered her space freely, not even reclaiming the costs of printing and publicity. She was withering about those rivals who tried to lock young painters into exclusive contracts: ‘I thought this was immoral when a painter already had something to say,’ she observed of a young Francis Picabia’s arrangement with the Galerie Danthon, ‘but even worse when they were just starting out.’ Instead she imposed no constraints on new talent and often took only minimal commission. While this outlook did little to keep her creditors at bay, it did allow her to form intimate relationships with the artists whose struggles she knew first-hand. The memoir suggests Weill that doubled up as a holiday companion, marriage counsellor and morale booster, stepping in to motivate and help out artists in distress (and sometimes their jilted girfriends). She also identified with their rebellious and experimental streak; although trading in academic painting seemed a more profitable venture, she never considered switching her loyalties, adding, ‘I would rather eat bricks than do something I disliked. So there!’

Pow! offers many vignettes of dealers, collectors and especially the artists for whom Weill was an early champion. It was quite a roll-call: the sandal-wearing lothario Kees van Dongen; Diego Rivera, who strutted into Paris like ‘Gulliver among the Lilliputians’ and quickly made enemies (‘I could easily imagine him putting out a fire by pissing on it’); and cheery, sincere Raoul Dufy, who restored her faith in ‘the painters of tomorrow’. Weill’s deep admiration for the talents of her stable did not blind her to their foibles: Picasso spoke French ‘pretty badly’, and glared at her resentfully for failing to pay him enough, whereas jealous Matisse was determined to stop Dufy from infiltrating Les Fauves, and Amedeo Modigliani was a terrible drunk, despite his ‘fine, refined mind, and superb head’. Memorable, too, are her anecdotes about some eccentric outliers, such as Adrien Barrère the ‘young junkyard sculptor’ who at the turn of the century depicted leading figures from European society, including Queen Victoria and Émile Zola, ‘as coloured plaster fetuses sealed in pharmacy jars’.

Portrait of Mme Zamaron (1922), Suzanne Valadon. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

The constant churn of exhibitions, and patchy documentation, means that we can identify only a fraction of the works that passed through Weill’s hands. The exhibition organisers have come up with some interesting approximations, which also showcase the sheer diversity of production in these years. Women artists featured in nearly a third of all the exhibitions Weill mounted (with 29 of 149 solo shows devoted to their work). She described Émilie Charmy as her ‘best friend’, in whom she saw something of her unwillingness to fit into ‘a pleasing, ready-made formula’, even though it made her unpopular. If Weill fondly called Charmy ‘elegant and a bit zany’, the latter’s portrait of Weill from the 1910s captured the dealer’s self-assurance and sharp intelligence. Weill also hugely admired Suzanne Valadon, another model of female resilience in the face of public criticism. ‘To her great credit, she never made any concessions,’ Weill observed. ‘A great artist!’ She also knew how to throw a party; in 1922 Weill attended a Christmas bash at Valadon’s home with dancing and singing till dawn.

Ball given at the pink house in Montmartre, Paris, int he 20’s : Suzanne Valadon (c), Berthe Weill (far right) Party attended by WEill (far right) in honour of Suzanne Valadon at teh Maison Rose in Montmartre, photographed by Primo Ballara. Private collection. © Bridgeman Images

Paris in these years was a magnet for artists from all over the world, and this internationalism was reflected in the programming at Weill’s gallery, which retained its character after the upsurge of xenophobia and antisemitism during and after the First World War. Weill’s advocacy of the work of all these international artists was loudly trumpeted in the pages of the Bulletin that she founded in 1923. It ran for 123 issues, a rare feat of longevity.

One fascination of dealer exhibitions is that they reunite items of stock which have since gone on to command very different prices and levels of renown. Weill’s sensibilities were broad, and seeing all the pictures together is an invitation to reflect on which of her ‘discoveries’ made it, when, and why. Weill’s memoir stops in 1926 with warnings about the growth of ‘scandalous speculation’ and the corruption of artists and collectors alike by ‘the spirit of lucre’. The grim years of the Depression only exacerbated the inequalities within the gallery system, and Weill was forced to put her personal collection up for sale in Switzerland, and move her premises across the river to the seventh arrondissement.

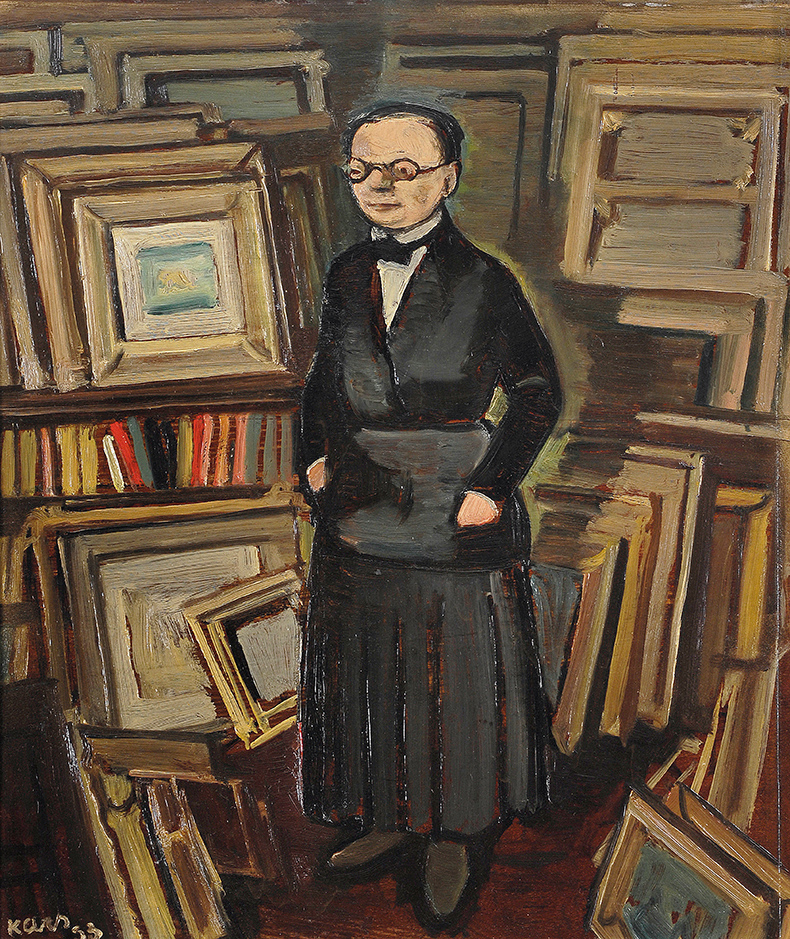

Berthe Weill painted in 1933 by the Czech artist Georges Kars in her gallery in Paris. Photo: Maxime Champion [Global Art and Image]

It was a belated accolade for a woman who for decades had persevered in a career that earned her little money or public recognition. Weill was the first to acknowledge that she had not been smart in commercial terms, and that her eccentricities could also push people away. ‘I’m stiff-necked, forbidding and I have a difficult personality […] I’m haughty and proud, and everything about me deters and discourages anyone with a notion to ask for my collaboration.’ Yet over the years she elicited gratitude and respect from her beloved jeunes, whose triumphs and reversals had provided the colour and drama of her life. She counted herself lucky that she did what she loved and, against all the odds, she managed to hang on. The transatlantic exhibition that will travel from New York to Montreal and Paris will show the tenacity of her commitment to modern art. For her resilience in a difficult market she well deserved the affectionate nickname of ‘la mère Weill’, a true marvel.

‘Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde’ is at the Grey Art Museum, New York, from 1 Oct–1 March 2025.

From the October 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.