From the December 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1762, the architect Jacques-Raymond Lucotte issued a print showing a mason’s workshop. Cartouches, pedestals and pillars are clustered in one corner; in the other, a labourer saws slices from an enormous marble block. Published as the entry for ‘marble work’ in Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s monumental Encyclopédie (1751–72), Lucotte’s print and explanatory text covered all the practical uses of marble: for paving, tiling and statuary. However, the stone itself was also well established in natural history collections as an object of both visual delight and scientific study. A decade after Lucotte, the German-born bookseller Jan Christiaan Sepp offered readers a similarly encyclopaedic look at its visual and geological properties. Originally published in Amsterdam in 1776, in a run probably not exceeding 100 copies, Marmora, or the Book of Marble, has now been beautifully reproduced in facsimile.

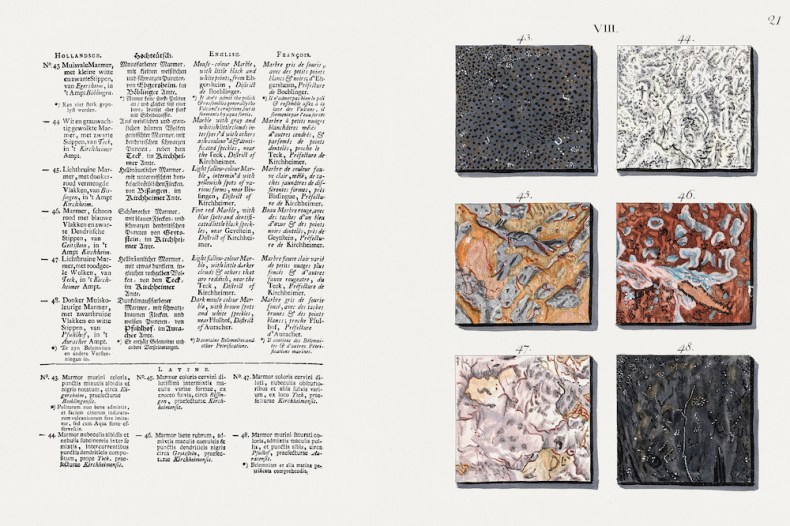

Sepp’s compendium of ‘different sort of marble ingraved and set out in their natural colours’ includes descriptive texts in French, Dutch, German, Latin and (occasionally faltering) English. However, the heart of the book is its 100 hand-coloured plates depicting the whorls, swirls, dapples and veins on 570 different types of marble. These were engraved by the natural history specialist Adam Ludwig Wirsing, who must have furnished detailed templates for the team of hand-colourists charged with adding pigment to black and white representations of such subjects as ‘fallow and mouse-colour variegated marble, interspersed with white veins and spots’.

As Sepp clarifies in the brief original foreword, ‘marble’ in this context meant any stone that could be polished for aesthetic effect, and supplements to the first edition include rock crystals, porphyry, jasper, basalt, lazulite and emerald, and the occasional fossil (Fig. 1). The book was popular with 18th-century interior designers and architects, but it was primarily aimed at the community of upper middle-class collectors that was expanding in the Netherlands and across Europe. Those collectors included at least two of the men involved in the book’s production. Casimir Christoph Schmidel, who wrote the text, had a significant collection of minerals; Sepp’s father, Christian, with whom Sepp traded in partnership, was a cartographer and insect collector. Over the course of the 18th century, such collectors could pick from an increasing number and range of reference publications. These were intended to help them itemise, compare and identify what they had got, or still needed, and Marmora can be compared with Dézallier d’Argenville’s popular guide to shell collecting, La conchyliologie (1757) or William Curtis’s translation of the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus’s Fundamenta Entomologiae; or, an Introduction to the Knowledge of Insects (1772). From 1791, Sepp began issuing the follow-up to the Book of Marble, the similarly exhaustive Science of Wood.

As Sepp clarifies in the brief original foreword, ‘marble’ in this context meant any stone that could be polished for aesthetic effect, and supplements to the first edition include rock crystals, porphyry, jasper, basalt, lazulite and emerald, and the occasional fossil (Fig. 1). The book was popular with 18th-century interior designers and architects, but it was primarily aimed at the community of upper middle-class collectors that was expanding in the Netherlands and across Europe. Those collectors included at least two of the men involved in the book’s production. Casimir Christoph Schmidel, who wrote the text, had a significant collection of minerals; Sepp’s father, Christian, with whom Sepp traded in partnership, was a cartographer and insect collector. Over the course of the 18th century, such collectors could pick from an increasing number and range of reference publications. These were intended to help them itemise, compare and identify what they had got, or still needed, and Marmora can be compared with Dézallier d’Argenville’s popular guide to shell collecting, La conchyliologie (1757) or William Curtis’s translation of the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus’s Fundamenta Entomologiae; or, an Introduction to the Knowledge of Insects (1772). From 1791, Sepp began issuing the follow-up to the Book of Marble, the similarly exhaustive Science of Wood.

Like many 18th-century collections, Marmora orders its samples by location of origin, and almost all Wirsing’s plates follow a standard template of six squares to a page. An illusionistic drop-shadow around each square gives the samples a three-dimensional quality, as if a group of marble tiles had been left sitting on the open book during the course of private study. At the same time, the uniform template draws the reader’s attention to the samples’ surface appearance and colour, concealing less relevant distinctions of shape and size, and facilitating a more precise – and scientific – system of observation and classification. Indeed Wirsing’s magnificent plates encourage the kind of careful looking familiar to the scientist, but also to another growing cohort of the 18th century: the art historian.

Marmora also demonstrates developments in 18th-century scientific publishing. Sepp was already an established producer of luxury editions on natural history, and Marmora used the most advanced reproductive and artistic technology available. Partly under the influence of Linnaeus, there had been a growing consensus since the 1730s that illustrators of natural history specimens should – as Linnaeus did – amalgamate anatomical features from several different examples to create the purest possible representation of the type. Numbers 45 to 47 in Marmora’s section on ‘Marble of Brabant’ (in present-day Belgium) are ‘straw and light ash-colour’ marbles with black, grey and brown veins. They were, Schmidel regrets, ‘not drawn copiously, the Quarry being under water, it caut [sic] be obtained without great expenses’, an apology which suggests that Wirsing must, to some extent, have been following contemporary scientific trends.

Page from Jan Christian Sepp’s Book of Marble. Photo: © TASCHEN/Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

The complete Marmora was issued in instalments and retailed at around 900 stuivers (around €450 today). The reissue is similarly lavish. A generously illustrated new essay by Geert-Jan Koot provides an overview of the 18th-century context and Sepp’s career. Koot is keen to stress Marmora’s status as an exemplar of Enlightenment values, describing it as ‘among the finest visual expressions of the […] pursuit of encyclopedic knowledge’. It is difficult to disagree. At the same time, plates such as ‘Florentinische Marmor’ no. 1 (‘Italian and Olden’), described in the catalogue as ‘pretended ruinous Marble, resembles the ruins of a destroyed Castle’, and Schmidel’s pervasive references to marble almost in personified human terms – ‘Liver-colour Marble, interspers’d with dark red drops’ and ‘Marble with […] blood-colour drops’ (Marbles of Wurtemburg, numbers 20 and 21) – suggest a playfulness more often associated with the curiosity cabinets of the 17th century than the scientific rationality of the 18th.

Detailed annotation of the text is beyond Koot’s scope, and his multi-lingual essay is necessarily brief. The interested reader may nonetheless wish for further detail on such topics as the practicalities, geology and geography of historic marble quarrying and processing, artists’ use of hardstones, and the contemporary state of knowledge about fossils and crystals. Several intriguing illustrations on these points are presented in the text with little explanatory discussion. However, these opportunities for further discovery speak more directly to the splendour and surprise of Sepp’s original publication. Like the 18th-century collector, the modern reader closes the book delighted – but perhaps still in search of more.

Jan Christiaan Sepp: The Book of Marble edited by Geert-Jan Koot is published by Taschen.