Anish Kapoor, Louise Bourgeois, Rachel Whiteread, Gerhard Richter. These may not be names that spring to mind when you think of the British Museum, but they all have work filed away in its extensive archive of prints and drawings. ‘Pushing Paper: Contemporary Drawing from 1970 to Now’ lifts a lid on a lesser-known collection at a museum renowned for ancient artefacts from all corners of the world.

Although it has often been viewed primarily as a preparatory exercise, drawing is here appreciated as an art form in its own right – and one that’s employed by many artists to navigate the modern world. Out of the museum’s collection of more than 1,500 post-1970 drawings, this free-to-visit exhibition brings together 56 works that show how the medium has developed as a mode of artistic expression. It encompasses myriad materials and processes, from pen-and-ink portraits to smudgy impressions of war generated from the rough application and erasure of charcoal on cardboard. What is clear throughout the show, which has been co-curated with four regional galleries where it will later appear, is how the definition of drawing has happily ballooned in recent decades.

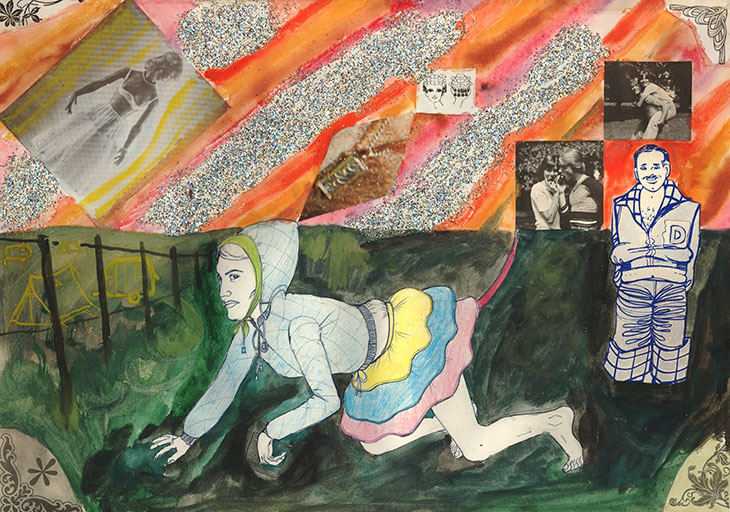

Untitled (c. 1984), Grayson Perry. Reproduced by permission of the artist; © The Trustees of the British Museum

Tracey Emin is an artist whose work discloses the most intimate aspects of her identity. My Abortion – 1990 (1995) shows a naked woman lying on a spindly-legged hospital bed, her own legs hanging open and her left hand resting on her womb. Sketchy and shaded, it represents the death of Emin’s foetus. Look closely and you’ll see a small figure, still attached by a knotted cord, floating up above her belly.

Not far from that dark monoprint is a gaudier form of self-exploration. Grayson Perry’s early representation of his alter ego Claire is crafted from crayons, gouache, glitter, collaged photographs, and more. Claire is portrayed in a pastel-coloured (very authentically ’80s) ra-ra skirt and a pale hoodie, prowling across a patch of grass like a cat, with bare feet and a pointed pink tail. She’s fleeing from the heteronormative images around her: a female mannequin in lingerie, cheesy shots of young couples from teenage magazines and an ogling middle-aged man. If only she could leap the fence.

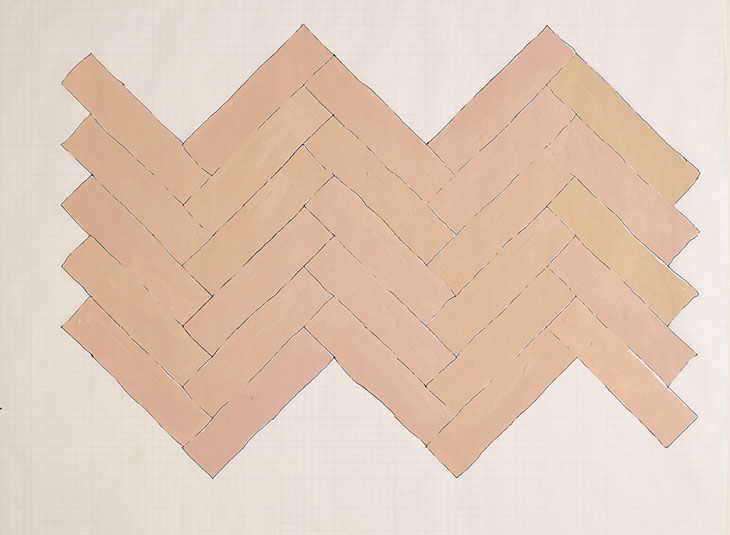

Pink (1993), Rachel Whiteread. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Rachel Whiteread created her first major series of drawings while living in Berlin in the early 1990s. The ink-and-gouache Pink (1993), which was inspired by the parquet flooring in her flat there, picks up on the themes of her sculptural work – her interest in domestic interiors and everyday materials. Beside it hangs Gerhard Richter’s Ohne Titel (Untitled; 1976), an illusionistic impression of an empty three-dimensional space created by the painstakingly meticulous marks of a felt-tip pen, ballpoint pen and graphite. A later section of the exhibition considers drawing as a time-based practice that can range from laborious to instantaneous.

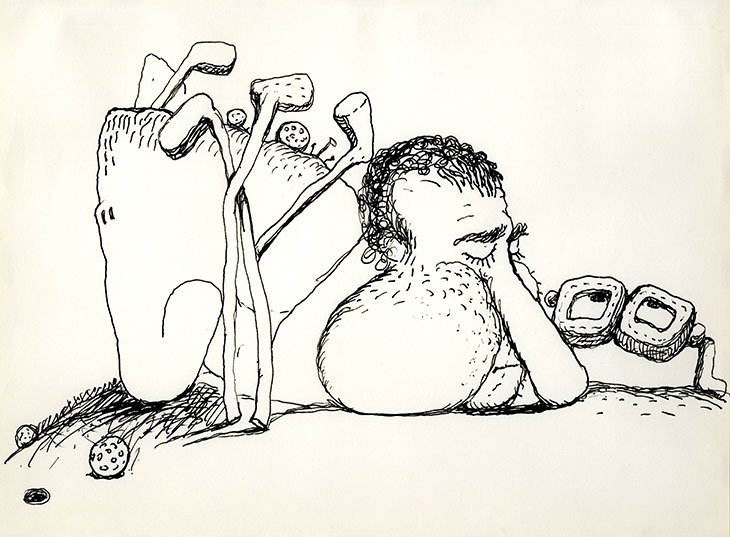

Time is surely of the essence for works that seek to challenge authority and comment on the state of a nation – such as the political cartoon, a form of drawing with a long tradition and represented here by Philip Guston’s Untitled (1971) from Poor Richard, a satirical series of some 180 works that chart the rise of Richard Nixon. The phallic depiction of the former US president, complete with flaccid nose, suggests Guston was not an admirer – and this was well before Watergate.

Untitled (1971), Philip Guston. Reproduced by permission of the artist’s estate; © The Trustees of the British Museum

Judy Chicago’s Driving the World to Destruction (1983) is another playful critique, this time of the patriarchy as a whole. After visiting Italy in 1982, and standing in front of too many Renaissance paintings that focused admiringly on the male nude, she decided to explore the idea of toxic masculinity and its grim repercussions for humanity. Her colourful sketch shows a burning globe and a muscular naked man at the reins.

The exhibition concludes with a clutch of drawings that address the artistic process itself. Bridget Riley considers the meeting points between multiple bands of colour while Anish Kapoor explores the nature of the void. Cornelia Parker has two works from 1997 hanging side by side: Poison Drawing, which contains ink mixed with rattlesnake venom, and Antidote Drawing, which contains white ink mixed with anti-venom. As Parker has observed, ‘If you did poison yourself on the first drawing you could break the glass and use the second drawing as a remedy.’ And there you have it: an artist pushing the medium of paper in a new, and daring, direction.

‘Pushing paper: contemporary drawing from 1970 to now’ is at the British Museum, London, until 12 January 2020. The exhibition will tour to other venues across the UK in 2020–21.