From the March 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Boasting is out, beauty is in,’ wrote Graham Hughes in 1963. And he was one to know: as art director and curator at the Goldsmiths’ Company, he had organised the first ever international exhibition of modern jewellery at Goldsmiths’ Hall, London, two years earlier. It was a display that showed what post-war jewellery could be, not only by intermingling antique and contemporary jewels but also by setting pieces from the great houses alongside experimental pieces cast from models by leading sculptors and artists of the day (including Elizabeth Frink, who designed an uncompromising pectoral). With these commissions, the Company began to collect studio art jewellery in precious metals. It supported the earliest experiments of a group of makers, including Andrew Grima and Charles de Temple, who have come to be known as ‘The London Originals’ – the subject of an exhibition in 2018 at Mahnaz Collection, New York, and of ‘The Jeweller’s Art’, a show currently at DIVA in Antwerp (until 14 March).

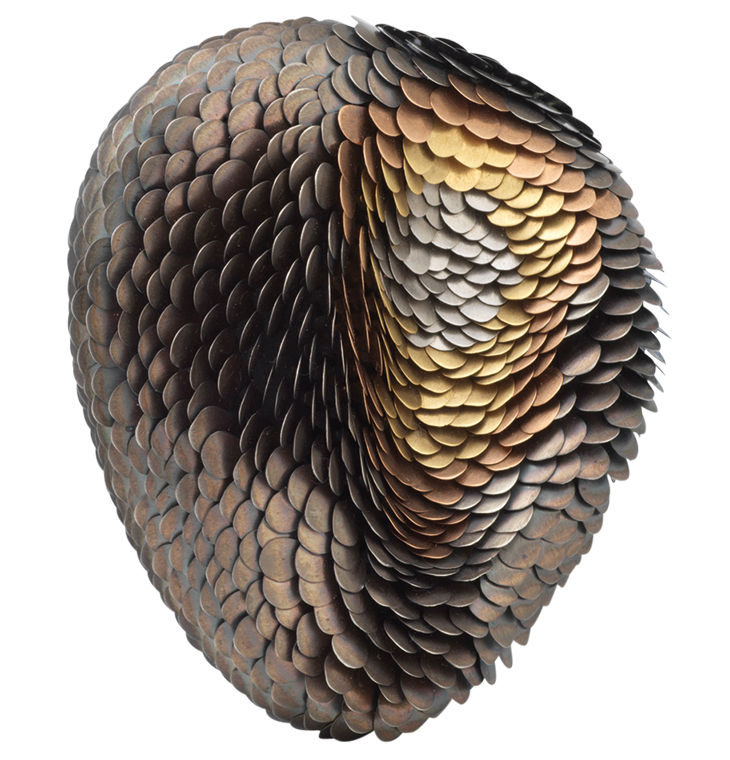

‘Amaru’ brooch (2019), Emmeline Hastings. Photo: Richard Valencia; The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths

The exhibition in 1961 helped to kickstart a new age of jewellery design. A central aspect of this was the reinvention of the brooch as an art form, as makers increasingly began to consider its volume, surface texture and materiality in sculptural terms – developments explored in ‘The Brooch Unpinned’, the Goldsmiths’ Company’s first digital exhibition, which I curated with colleagues last year, and which will soon be a physical exhibition at the Goldsmith’s Centre in Clerkenwell. The exhibition spans the period from 1961 to the present day, testament to how the Goldsmiths’ Company continues to promote innovation in studio art jewellery. The ‘Amaru’ brooch commissioned from Emmeline Hastings in 2018, for example, allowed her to develop her signature technique of embedding precious metal scales into acrylic into something more kinetic and dramatic. One of her pieces recently appeared in a science-fiction thriller, Max Steel (2016) – an apt setting for work that has a timeless quality, alluding to the ancient world but at home in an imagined future. Kayo Saito’s ‘Moon Brooch A’ (2020) similarly connects old and new; its marble moon seen through textured gold leaves is rendered in a contemporary aesthetic but recalls a classical Japanese poem about the experience of loss and separation on seeing the moon from another country than one’s own.

‘Moon Brooch A’ (2020), Kayo Salto. Photo: Clarissa Bruce; The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths

The exhibition was partly inspired by the capacity of a single brooch – Lady Hale’s diamanté spider – to spark a global conversation. But what we particularly wanted to explore were the sculptural qualities of our brooches, using the potential of our digital platform to display pieces from multiple angles and magnify details that would be difficult to see in a physical exhibition. We were keen to explore the backs of brooches, as well as their fronts, to convey their microengineering and to take people closer to hallmarks, which place each brooch within an artist’s biography. With libraries and archives closed, it wasn’t easy to research the pieces during lockdown. But that threw us back on the Goldsmiths’ Company’s unique resource: the makers themselves, with whom we had long conversations about pieces in the collection.

Researching each brooch took us deep into the stories of individual makers. Textured gold was key to the 1960s look; Andrew Grima once recalled ‘experimenting with all the techniques available at the time to make gold look like a material which nature might have produced.’ He often chose to use gemstones in their rough, crystalline form, as in a brooch set with a single rose quartz in an 18 carat gold frame, held in place with three white gold bars with pavé-set diamonds. The border is made from crumpled collets of soft 24 carat gold made from ‘diets’, or fragments of fine metal removed for assaying in the London Assay Office at Goldsmiths’ Hall, which were typically returned to the maker for recycling. Grima re-used them as they were, however, making them resemble barnacles that have somehow grown organically around the stone. This talent for upcycling had been determined by his experience of mending jeeps in Burma during the Second World War. According to Graham Hughes, ‘if you waited for promised supplies, you might wait for ever because they had been misdirected, bombed or stolen. It was usually better to make them yourself. So [Grima’s] repair group became known throughout the 14th Army because it hardly ever abandoned anything. There was no such thing for Andrew as scrap, only the possibility of re-use.’

Bling finger: Honor Blackman at the premiere of Goldfinger in 1964. Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

A brooch by another London Original, Charles De Temple, is an early and utterly characteristic example of his work: a sculptural form in organically shaped, textured silver-gilt, set with a cabochon amethyst. De Temple trained first as a circus artist and actor before from 1957 turning to jewellery in London. His ensuing success is a reminder of just how conspicuous studio art jewellery became in the fashionable London of the ’60s: De Temple quickly won clients in the worlds of pop, film and fashion. He even made the gold finger for the Bond film of that name in 1964, worn by Honor Blackman at the premiere in London.

Brooch (1963), John Donald. Photo: Clarissa Bruce; The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths

Created by John Donald in 1963, a rose-pink quartz brooch with radiating gold spokes was based on a Catholic silver monstrance he had seen on a travel scholarship to Italy in 1955. This is the piece that appealed most to our online viewers, who were able to try it on virtually in our exhibition using an Instagram filter that allowed users to ‘wear’ brooches on videos of themselves. And that’s no surprise: anyone who has a John Donald brooch from the ’60s holds on to it as something that never loses its appeal. When I managed to prise Donald from his greenhouse during lockdown, I asked him what had appealed about the brooch in those years. ‘Designs were always experiments in form,’ he said. ‘[They were] small sculptures or three-dimensional painting. In the early days, there were times when I thought to supply an appropriately sized picture frame where the brooch could be pinned and viewed as pure artwork, without reference to or influenced by the wearer.’ From 1961 onwards, brooches did indeed become an art form: one that was versatile, wearable and contemporary, and through which makers expanded what was possible with precious metals.

For more information on ‘The Brooch Unpinned’, visit the Goldsmiths’ Centre’s website.

From the March 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.