From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Skilful carving makes for better eating. That at least was the opinion of one 17th-century authority on the subject, who argued that the clumsy slicing of meat might cause offence at once visual and visceral. ‘The disorderly mangling a Joynt or Dish of good meat,’ he wrote, ‘is not onely an unthrifty wasting of it, but sometimes the cause of loathing, to a curious Observer, or a weak stomack.’

The anonymous author claimed that, with The Genteel House-keepers Pastime (1677; 1693 edn.), he was the first in England to set down in print principles for the proper carving of fish, flesh and fowl. This was an embellishment. In fact the earliest printed carving instructions in English date to 1508, when Wynkyn de Worde, a close collaborator of William Caxton, published a short manual called The Boke of Kervynge. This opens with a memorable catalogue of terms for dismantling birds and beasts, which would itself frequently be reprinted in later cookery books such as Robert May’s The Accomplisht Cook (1660): ‘Break that deer, leach that brawn, rear that goose, lift that swan…’.

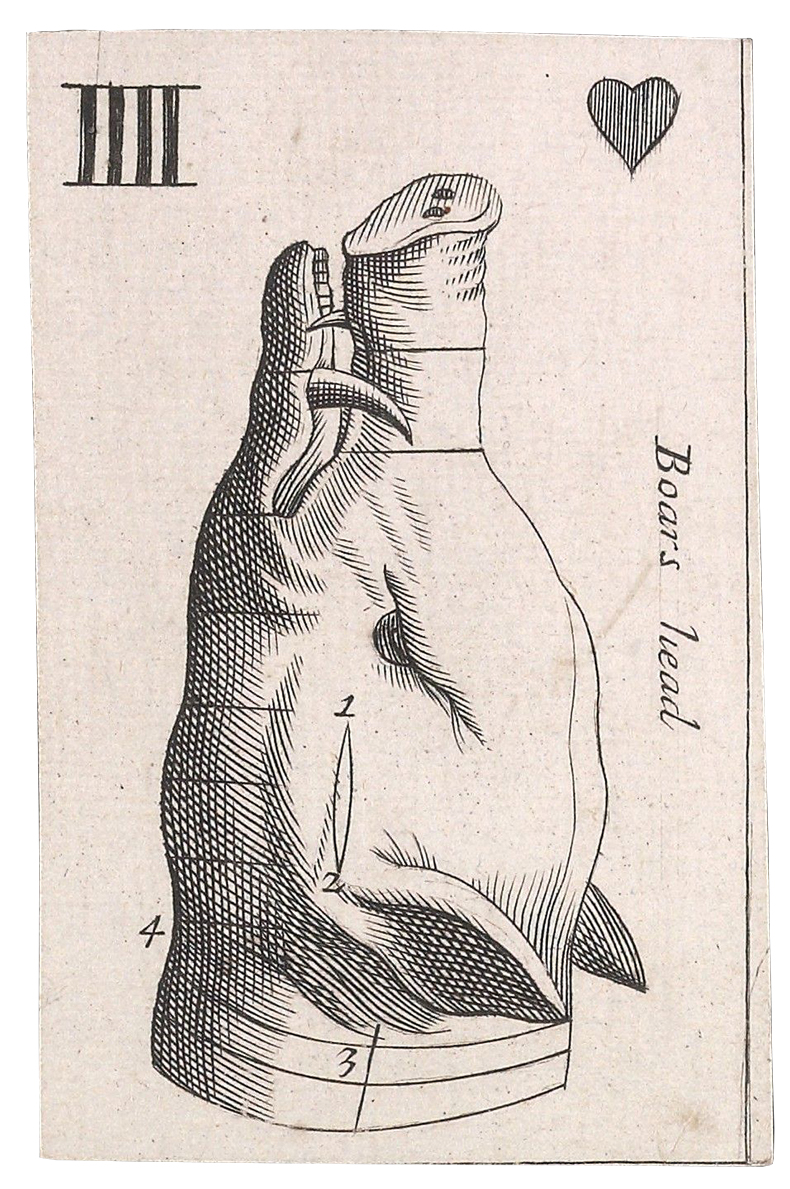

What made The Genteel House-keepers Pastime original, however, was that it was accompanied by a deck of playing cards, issued by Joseph Moxon, which illustrated dishes and provided figure references that correspond to the text’s explanations of carving procedures. Each suit coincides with a discrete category of food: diamonds for fowl; hearts for ‘Flesh of Beasts’; clubs for fish; and spades for ‘Baked Meats’ or savoury pies. In some cases, the higher-value cards play host to the most flamboyant dishes. The king of spades shows an elaborate venison ‘pasty’ (a double-crust pie); the king of hearts, the ‘Sir Loyn of Beef’, the grand slab of meat barely contained by the edges of the card.

Carving was a skill that had encouraged innovative illustration in early printed books. It was a refinement deemed worthy of such endeavours, too, with the office of carver a distinguished position in many noble households across Europe. Il Trinciante (The Carver; 1581), a treatise by Alessandro Farnese’s carver, Vincenzo Cervio, includes woodcuts that depict carving knives, forks and a carving iron, some ostensibly to actual size – as though encouraging the practical reader to pluck a blade from the page. Another book of the same title, devised by Mattia Giegher in 1621, emphasises both performance and precision in plates that show skewered joints, in some cases as though brandished in the air, which are marked up with red lines to indicate the prescribed sequence of cuts.

A 17th-century playing card showing how to carve a boar’s head. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

The illustrations on the carving cards are more rudimentary – although those for dishes that have become unfamiliar, such as a boar’s head or a pike, its body splayed in a loop, are undeniably striking. They summarise the volume and in some cases the texture of their subjects through crude hatching and cross-hatching techniques. All the same, their creators seem to have appreciated the consonance between the incising of engraving plates and the slicing of meat. The author remarks on the ‘curious engraven Cuts, accommodated to Playing Cards’, eliding roasted bits of beasts with their method of illustration.

Instructional playing cards proliferated in England after the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy, with printers taking advantage of the rescindment of a Puritan ban on card games and seeking to distinguish their own products through novel selling points. Decks took on subjects astrological, cartological, heraldic and typographical, or illustrated miniature accounts of events such as the Titus Oates plot. But even in this context the carving cards stand apart as a witty and uncommonly domestic contribution to the genre. They went to multiple editions over several decades.

That wit is apparent in imagining how the cards might have been used. They were never intended to elevate an idle game of cards in the kitchen; the cards and instructional manual required separate purchases, after all, and the cards themselves were heavily taxed. And for all that the author of The Genteel House-keepers Pastime insisted that ‘you may hold the Card in your hand all the while you are reading the Rules relating to it’, and stressed the carving was an art at once anatomical, arithmetical and geometrical, it is difficult to conceive of the deck in practical use by would-be master carvers. The turkey design, for instance, which is supplemented by five pages of carving guidance, is even less legible than the diagrams in an Ikea flatpack.

In the playing of card games, however, this deck would have thrown up pleasing ironies. To deal the cards was akin to the carver’s dividing of a dish into ‘services’ (servings). These were meant to be equal, as though each guest were dealt the same hand, but the carver also had to attend to a pecking order whereby the prized parts of any joint would be served to the most important people at the table. These cards upended the exactitude of carving – transforming it, after dinner, into a game of chance.

From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.