From the February 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The Louvre’s latest exhibition ‘A New Look at Cimabue: At the Origins of Italian Painting’ , curated by Thomas Bohl, is conceived around the two contrasting masterpieces now in the museum’s permanent collection by the early Tuscan artist Cimabue (c. 1240–1302). With more than 40 loans, the show sets these two paintings in the context of Cimabue’s career and the oeuvres of his contemporaries Duccio and Giotto. Drastically different in scale, the pair entered the Louvre by radically different routes, one by imperial design in 1813, the other by domestic serendipity in 2023. Both are revelations, amply justifying the exhibition title.

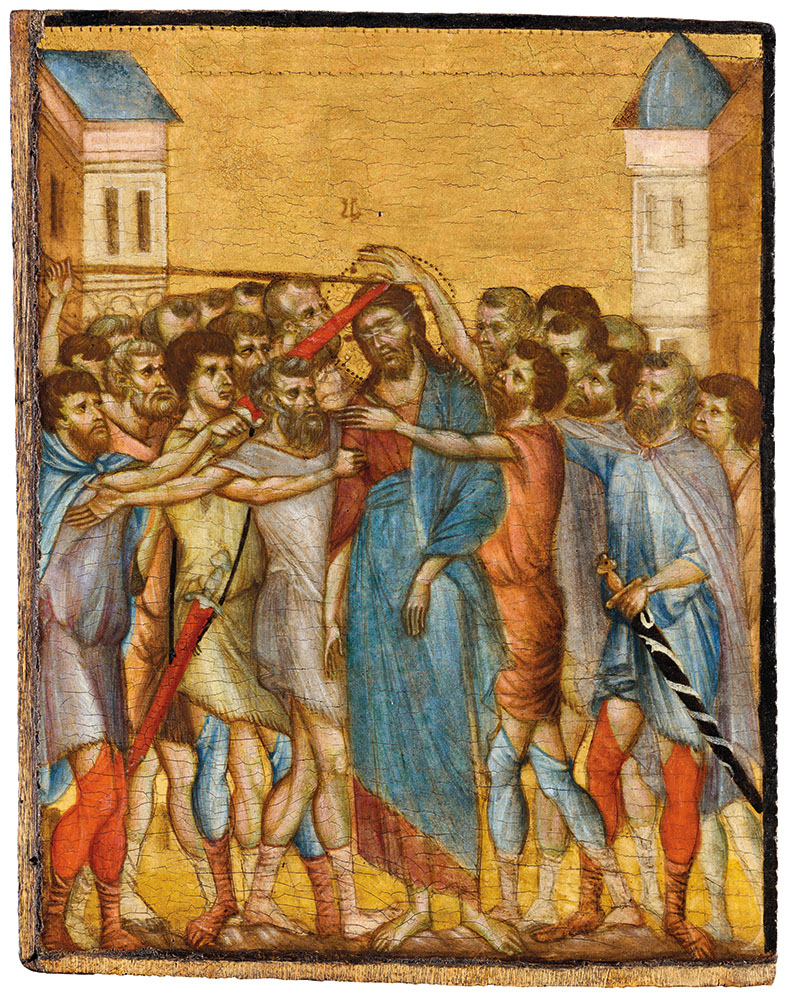

This is the first chance for the public to see Apollo’s acquisition of the year for 2024: the small panel of the Mocking of Christ discovered hanging over a stove in Compiègne in the summer of 2019 and sold at auction for €24 million later that year. The French government quickly placed a 30-month export block on the picture and declared it a ‘Trésor National’, thereby allowing the Louvre time to raise funds to purchase it for the state. It was formally acquired in November 2023 but has been undergoing conservation and technical analysis since then.

Its big sister, the enormous Virgin and Child Enthroned or Maestà, has been in the Louvre since the time of Napoleon, but visitors to the exhibition will be forgiven for not recognising the painting in the show for the murky and bafflingly large picture that rarely detained gallery-goers trooping their way towards the Mona Lisa. A major cleaning and conservation campaign has revealed the Virgin’s electric ultramarine mantle and a wealth of modelling, colour and surface decoration. The frame has been freed of its heavy repainting and the diminutive saints in the border roundels can be seen by modern eyes for the first time, effectively as new works, including a Saint Francis to set beside the artist’s famous portrayal of the saint in the frescoes of the Lower Church at Assisi.

Maestà (c. 1280), Cenni di Pepo, called Cimabue. Musée du Louvre, Paris

While the path of the Mocking of Christ from Italy to Compiègne remains mysterious for now, the arrival of the Maestà in 1813 was a carefully orchestrated affair of state. In 1811, with Italy under French rule, Dominique Vivant Denon – the first director of the Louvre – toured the peninsula to select works to send back to Paris for the comprehensive display of the history of painting envisaged for the megalomaniac project that was the Musée Napoléon (as the Louvre was rechristened during the First Empire). The pickings were especially rich in Tuscany, where the monasteries and convents of the religious orders had just been dissolved and their artworks appropriated by the secular authorities. Denon’s interests, unusually for the time, extended back to the primitifs of the 13th and 14th centuries. Following Vasari, his narrative of Italian painting would begin with Cimabue, the ‘first light’ of the Renaissance. In Pisa he found what he was looking for in the storerooms of the Camposanto, where the pictures from the city’s religious houses had been gathered by the conservator Carlo Lasinio. Here Denon alighted not only upon a signed work by Giotto, the Stigmatisation of Saint Francis, but also the mighty Maestà, authenticated as a work by Cimabue in Vasari’s Lives. With these pictures Denon would be able to tell the full story of Italian painting and could display the comparison between Cimabue and Giotto immortalised by Dante in the Purgatorio: ‘In painting Cimabue thought he held the field, but now Giotto has the cry, so that the other’s fame is dimmed’.

After their selection by Denon in 1811, these paintings and others left Pisa by boat on 24 October 1812, arriving in Paris in early 1813. Crating and transporting the Maestà must have been a challenge. The panel measures 424 x 276 cm (only Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna in the Uffizi is larger among comparable works from the period) and today weighs 288 kilograms. The support, however, was substantially thinned in the 1840s and its original mass may have been closer to half a metric ton. Even now, moving the picture is a considerable undertaking. The Maestà has never left the Louvre since its arrival from Italy. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, commissioners from the Grand Duchy of Tuscany arrived in Paris in September 1815 to select artworks for repatriation – remarkably, they chose to leave the Cimabue and the Giotto behind, considering them ‘mediocre’ and citing the ‘extremely heavy and large panels’ on which they were painted, which would ‘require an unmerited expense of packing and shipment’. Their indifference reminds us that Denon was ahead of most of his contemporaries in his appreciation for Italian gold ground painting: it would be another century before Cimabue’s Santa Trinita Maestà and Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna would be welcomed into the Uffizi.

Mocking of Christ (c. 1285–90), Cenno di Pepe, called Cimabue. Musée du Louvre, Paris

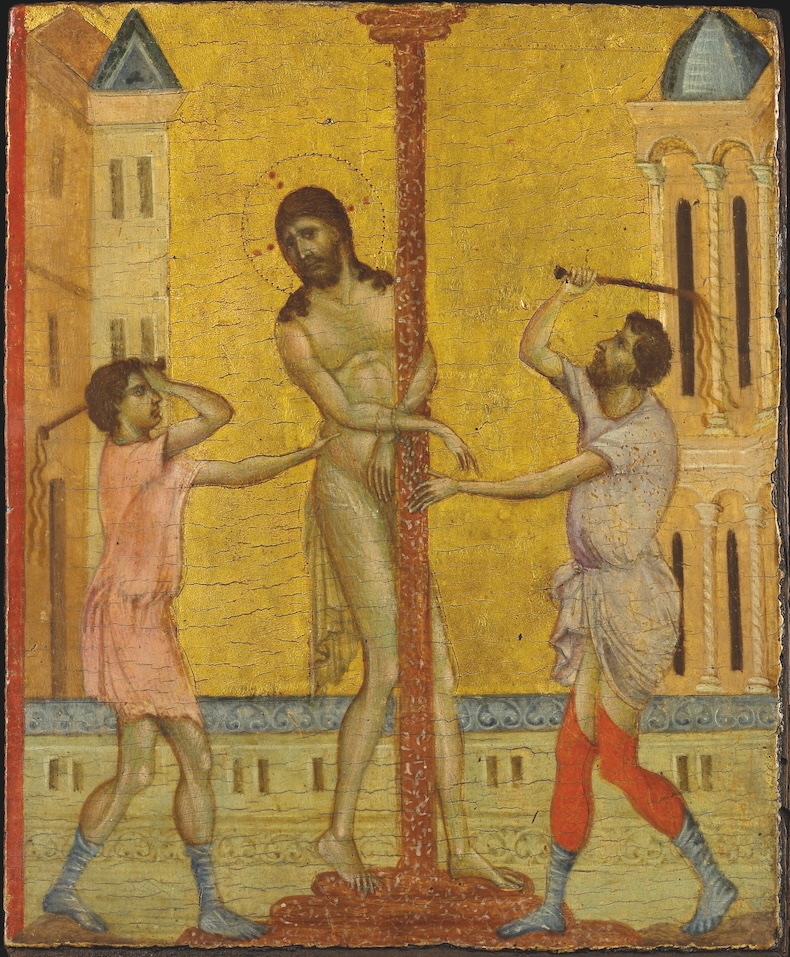

‘A New Look at Cimabue’ thus aligns elegantly with the founding vision of the Louvre, but the show is also an opportunity to consider the Mocking and the Maestà with the benefit of the latest technical analysis and recent art historical research. Conservation of the Mocking has confirmed what scholars supposed when the picture first emerged in 2019: it is a third fragment after the Flagellation of Christ in the Frick and the Virgin and Child with Two Angels in London’s National Gallery from what must have been a series of eight scenes, originally arranged into two quartets as two wings of a diptych (all three known pictures are from the left-hand valve). The Flagellation was first published by Millard Meiss (as by Duccio) in 1951, while the Virgin and Child was discovered under a staircase in rural Suffolk in 2000. When the latter picture came to light, the great Hungarian scholar Miklós Boskovits drew a connection with another, later set of eight scenes by the anonymous Maestro di San Martino alla Palma, dateable to c. 1320 – his suggestion was published by Dillian Gordon in Apollo in June 2003. Boskovits argued that Cimabue’s panels came from a diptych of the same format as the Maestro di San Martino’s, while Gordon further speculated that the later artist may have had first-hand access to Cimabue’s work as a model. As I wrote in this magazine in 2019, the discovery of the Mocking in France cements the correspondence. Unfortunately, we cannot compare Cimabue’s Mocking with its matching panel from the Maestro di San Martino alla Palma set. Having entered the Barlow Collection in Lancashire, this picture was destroyed in the bombing of Manchester during the Second World War, leaving us with only a black-and-white photograph.

The link between the two sets of paintings provides the few clues we have for the original context for Cimabue’s scenes. From the presence of both Saint Francis and Saint Clare in the Crucifixion, now in Berlin, from the Maestro di San Martino series, the later diptych can be identified as a commission for a convent of Clarissan nuns. Furthermore, the anonymous artist seems to have worked only in and around Florence, so the list of possible Clarissan houses is short. The Maestro di San Martino’s patrons most likely desired a copy of an older image that was already an established focus of Clarissan devotion, perhaps at a sister convent to which they had access.

Detail of the Saint Francis figure from the lower frame of the Maestà. Photo: © Thomas Clot/C2RMF

We may never reach a final answer for the commission and ultimate provenance of the Mocking and the diptych it once formed a part of, but the evidence points to a Clarissan community close to Florence. The format falls neatly within a broader tradition of Clarissan imagery that fostered close devotional engagement with specific episodes of Christ’s Passion. It is notable that the eight scenes would have made equal demands on the viewer: there is no central image to provide a natural devotional focus. The composition of the diptych would have encouraged its audience to examine all the scenes without privileging one over another. As Cimabue expert Holly Flora has noted, the Mocking and its companion narratives thus offer a visual parallel to the immersive retelling of Christ’s Passion in the Meditations on the Life of Christ, the most popular devotional handbook of the later Middle Ages which was being composed at almost the same time for a Clarissan convent in nearby San Gimignano. (Fittingly, the most richly illustrated surviving copy of the Meditations is on display in the Louvre’s exhibition.)

The Flagellation of Christ. (c. 1280), Cenno di Pepo, called Cimabue. Frick Collection, New York

Turning our attention to the monumental Maestà requires a sharp shift of perspective, away from the intense devotions of nuns at close quarters within their cloistered spaces to the monumental and public setting of a major church interior. Vasari recorded the Maestà in the Pisan church of San Francesco, under construction from 1261 onwards and largely complete by the end of the century (Denon’s other Pisan acquisition, Giotto’s Stigmatisation, came from the same church). Vasari saw the Maestà in the 1560s by the side door of the nave, but this is unlikely to have been the location for which Cimabue painted it. For one thing, it never seems to have been associated with any of the altars in the church. Recent studies have shown instead that large gabled panels like the Maestà were often displayed above rood screens or beams, in arrangements similar to that recorded by Giotto in his fresco of the Verification of Saint Francis’s Stigmata in the Upper Church at Assisi, painted c. 1292. While any rood screen in San Francesco had already been demolished by Vasari’s day, unpublished documents in the Florentine state archives indicate that the church did indeed possess one, with a crucifix above its central doorway.

Over the course of the past year, I have worked with my PhD student Lucas Giles and professor Marco Giorgio Bevilacqua and Piergiuseppe Rechichi of the University of Pisa to visualise for the exhibition a hypothetical reconstruction of a screen structure within San Francesco. The church itself still stands, but its recent history has been troubled. The roofing over three of the transept chapels collapsed in September 2015 and the building was closed permanently in April 2016. The vast interior is now filled with a forest of scaffolding to support the precarious roof trusses, but the Pisan Soprintendenza is on the verge of awarding contracts for the multimillion-euro restoration of the church, with philanthropic support from the Fondazione Pisa.

A view of the reconstruction by Piergiuseppe Rechichi, Donal Cooper, Lucas Giles and Marco Giorgio Bevilacqua showing how Cimabue’s Maestà might have looked in its original setting in the church of San Francesco, Pisa. Digital image: © Rechichi, Cooper, Giles, Bevilacqua

Our reconstruction incorporates Cimabue’s Maestà alongside a now-lost crucifix and Giotto’s Stigmatisation. To realise this. Piergiuseppe Rechichi created a digital replica of the church within which we were able to test different solutions for a screen arrangement. San Francesco is a remarkably wide church, so we propose a screen divided into five bays, which would have sheltered chapels below its arcade. A central doorway would have given a clear vista towards the high altar while the upper storey would have served as a preaching platform. Our most difficult decision was how to mount the panels. Recent work by Fabio Massaccesi indicates that panels were often mounted on beams that were set above screens.

These combined screen and beam arrangements allowed a privileged audience on top of the screen close-up access to these large panels, while the general congregation in the nave enjoyed a more distant but still uninterrupted view. Giotto’s Stigmatisation seems to have been composed with these contrasting viewpoints in mind, combining a banner-style main image with a lower predella crammed with intricate narrative, the patron’s coats of arms and – perhaps most tellingly – the artist’s signature. The recent conservation campaign has also revealed for the first time a wealth of detail and decorative effects on Cimabue’s Maestà, even in the diminutive saints along the border – here too, there would have been much to tempt the viewer.

Our reconstruction is perhaps best characterised as a ‘provocation’ (a usage coined by the archaeologist Ian Haynes), which will inspire further research and reflection. In the current exhibition it will help the public to better understand the disconcerting dimensions of the Maestà, to appreciate how its scale was keyed to the building it was designed for, and how its design was integrated with a monumental screen – a structure that will be surprising and strange to many. Approaching the newly restored Maestà, one can only marvel at the exquisite passages of detail and ornament across such an enormous work. Although in scale the Louvre pair are polar extremes, they both reward the opportunity for closer scrutiny.

‘A New Look at Cimabue: At the Origins of Italian Painting’ is at the Musée du Louvre until 12 May.

From the February 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.