The circumstances are extraordinary: discovered hanging over a hotplate by a local auctioneer conducting a house clearance in provincial France in June, Cimabue’s Mocking of Christ will go under the hammer at Actéon in Senlis on Sunday 27 October with the firm expectation of a multi-million euro sale. It joins fewer than ten accepted works on panel by the artist immortalised by Dante and Vasari as ‘the first light’ of Italian painting, only for his fame to be eclipsed by his pupil Giotto.

While there have been some predictable grumblings in the press over the painting’s authenticity and attribution, this appears a clear-cut case: if the Mocking is somehow an intelligent fake, technical investigation should swiftly rumble it. Every aspect of the new panel identifies it as a companion to two others of near-identical size attributed to the Florentine master: the Flagellation in the Frick collection in New York and the Virgin and Child with Two Angels in the National Gallery, London, itself a relatively recent arrival, discovered in Suffolk in 2000 and fully published for the first time in Apollo in 2003 by Dillian Gordon (who had managed to acquire the panel for the gallery through the UK government’s Acceptance-in-Lieu scheme before it went to auction). Let us hope that the Mocking of Christ’s future home will be similarly accessible to the public.

The newly discovered picture is causing considerable excitement among scholars of early Italian painting, kindly communicated to the present author by email correspondence. Holly Flora, curator of the 2006 exhibition at the Frick that reunited the two related panels and author of the most recent monograph on Cimabue, believes that ‘this discovery will lead to a deeper understanding of how Cimabue contributed to the development of narrative devotional painting at a crucial moment of change in the history of art’. Andrea De Marchi, the leading Italian authority on the period, stresses that ‘for the first time, we have one of Cimabue’s greatest qualities, that of choral narration, of the crowding of figures – so evident in his frescoes at Assisi – in a small-scale panel painting’. Joanna Cannon of the Courtauld Institute adds that ‘the density of movement, interweaving gestures and exchanged looks is masterly, offering the viewer multiple points of focus, converging on the dominant central figure of the standing suffering Christ’.

The Mocking of Christ (c. 1280), Cimabue. © Actéon

Cimabue’s iconographic choices are fascinating. The standing Christ owes more to Byzantine precedents, whereas some of his Tuscan contemporaries were already – as Anne Derbes has shown in her exacting analysis of 13th-century Passion imagery – adopting the seated, blindfolded Christ typical of Northern European stained glass and manuscript illumination. The figure at far left striking Christ with a lengthy reed is known from Byzantine comparisons, as is the man poised to slap Jesus with his stretched-back arm. But the manner in which Cimabue knits these figures together and into such a tightly interlocked, emotionally charged crowd is utterly distinctive and new. The complex, deliberately confusing chain of limbs running across the picture invites the viewer to decipher each figure’s role and action and acts as a decisive counterpoint to Christ’s limp arms as he passively accepts his ordeal. The two sheathed swords set symmetrically to left and right provide compositional clarity to offset and accentuate the frenzy of the scene, directing our attention diagonally upwards to the picture’s focal point, Christ’s sorrowful face and the forceful gestures that surround it – the fingers clutching his shoulder, the arm across his chest, the slapping hand that seems to pull away his halo, the hard edge of the sword striking down on his temple (we have to look twice to see that it is not a naked blade). This little painting is a narrative gem and surely the work of the master rather than his bottega.

The Flagellation of Christ (c. 1280), Cimabue. The Frick Collection, New York

Even on the basis of available photographs, the discovery substantially clarifies our understanding of the scale and format of the larger work of which it was originally part. (The sale catalogue published by Actéon also presents some important preliminary technical analysis including an infrared reflectogram that reveals Cimabue’s underdrawing.) The edges of the new panel are not alike. The bottom and left sides possess clear ‘barbes’ where there is an abrupt tear-like break between the raised paint surface and the wooden support: these are tell-tale signs of an engaged frame having been removed. By contrast, the top and right sides, although marked with paint losses, are free of such barbes. Here the gold ground is bound by a simple painted border without any transition in the picture surface. These bands appear black or dark blue, perhaps the result of repainting on all four sides to create the impression of an even frame (the exposed wooden supports at left and bottom seem to have received the same treatment). Further technical analysis will confirm whether there is red beneath the blue to match the painted borders still visible on the Frick (left-hand side) and National Gallery (right-hand side and bottom) panels.

The French auction house has apparently been able to confirm that the National Gallery’s Virgin and Child was directly above the Mocking in the ensemble by matching the new panel’s grain and wormholes with a photograph of the verso of the London picture. Given that barbes establish the Virgin and Child in the upper-left corner and the Mocking at the bottom-left on the original panel, this would confirm that there were only two registers of scenes, as Gordon has proposed. The barbes on the Frick panel, meanwhile, place it in the lower-right corner and we might expect the Flagellation to have followed the Mocking in terms of narrative sequence. A photomontage of the backs of all three scenes is included in the Actéon catalogue. While the verso of the Frick Flagellation is mistakenly placed to the wrong side of the Mocking, and a vertical break along the grain is harder to read than a horizontal cut against it, the montage suggests that there will also be a carpentry match with the New York picture.

It is to be hoped that the Mocking will benefit soon from a full technical examination, but for now the available evidence seems to point clearly towards the surviving trio of panels being three scenes from a quartet of four, divided internally by painted bands and externally by an engaged frame before they were sawn into separate pieces. Only the upper-right scene is missing. Gordon, developing a suggestion by Miklós Boskovits, has already used the evidence of the barbes and painted borders on the Frick and National Gallery pictures to draw a comparison with a series of eight panels by the anonymous Maestro di San Martino alla Palma painted in c. 1320 that Boskovits had reconstructed as a diptych with two valves each comprising four scenes.

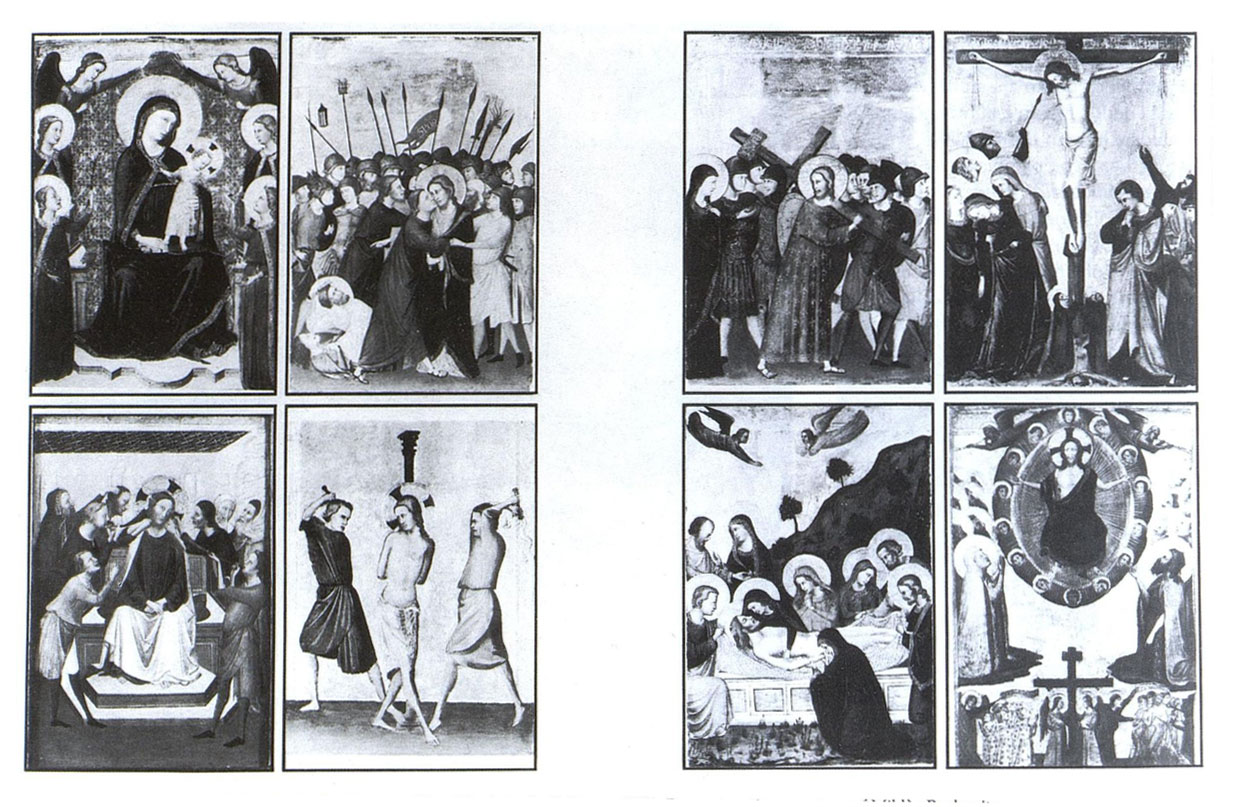

Miklós Boskovits’s reconstruction of eight panels by the Maestro di San Martino alla Palma, painted in c. 1320, as a diptych. This reconstruction was published in Dillian Gordon’s article ‘The Virgin and Child by Cimabue at the National Gallery’ in the June 2003 issue of Apollo

Boskovits and Gordon observed that the left wing of the Maestro di San Martino diptych also incorporated the unusual combination of the Virgin and Child with Angels and Flagellation, and Gordon further suggested that the anonymous trecento painter may have taken Cimabue’s work from several decades earlier as a direct model for the iconography and format of his diptych. This persuasive comparison now becomes compelling with the discovery of the Mocking of Christ, the clarification of its position relative to the Frick and National Gallery pictures, and confirmation that the surviving panels are three from a quartet of four. Again there is a perfect match with the left-hand wing of Boskovits’s reconstruction of the Maestro di San Martino diptych to give a remarkable accumulation of coincidences. The two series are also close in scale: 29.2–31.4 x 21–21.5cm for the Maestro di San Martino’s scenes, compared to 25.2–25.8 x 20.3–20.5cm for Cimabue’s. Perhaps there were other diptychs in the same format, but given the precise formal parallels and the distinctive combination of scenes, Gordon’s suggestion that the Maestro di San Martino’s direct model was Cimabue’s older painting now stands as the most plausible explanation for their multiple correspondences.

The Virgin and Child with Two Angels (c. 1280–85), Cimabue. © The National Gallery, London

On this basis – and mindful that any hypothesis may well be overturned should, as we hope, further fragments come to light – it is tempting to extrapolate the evidence of the Maestro di San Martino diptych to identify the missing scenes from the Cimabue sequence. Following this logic, the remaining scene on the left valve would be a Betrayal, and – as Cannon perceptively notes – the composition of the Mocking may echo the crowds jostling Christ in a Betrayal scene. Meanwhile, the four scenes on the right valve would be the Way to Calvary, Crucifixion, Entombment, and Last Judgement. The Maestro di San Martino series is also valuable as it preserves internal evidence for its patron. The presence of St Francis and St Claire kneeling at the foot of the cross in the Crucifixion now in Berlin, as Gordon and Boskovits have argued, strongly suggests a Franciscan context, most probably a community of Clarissan nuns. The importance of narrative cycles of the life of Christ on panel for Clarissan communities has been convincingly demonstrated by Flora, Victor Schmidt and Michaela Zöschg. A well-preserved diptych of similar format painted in c. 1300 by a Venetian artist now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts combines a different selection of six Passion scenes with a Last Judgement and a Virgin and Child flanked by St Francis and St Claire and helps us to visualise the original appearance of both Cimabue’s and the Maestro di San Martino’s ensembles.

While the Virginia diptych is a valuable comparison, the relationship between Cimabue’s and the Maestro di San Martino’s series is much closer and best explained by the desire of the latter’s Clarissan patron for an updated version of an earlier work that fulfilled the same devotional needs, probably one belonging to her own convent or another in the region that was known to her. On the basis of the Frick and National Gallery panels, Flora had already proposed that Cimabue’s cycle should be considered the earliest identifiable example of this tradition of Clarissan devotional image. The new discovery significantly strengthens her reading.

Eight Scenes from the Life of Christ (14th century), Italy. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

If we deduce that the Maestro di San Martino alla Palma had direct access to Cimabue’s diptych, that connection would also have implications for the provenance of the Mocking and its companion panels. Clarissan nuns were strictly cloistered and we cannot assume that artworks identified for their devotional use were easily accessible or freely circulated. Gordon cautiously identified the National Gallery Virgin and Child with a small ‘Madonna di Cimabue’ recorded in 1829 among the pictures in the possession of Carlo Lasinio, keeper of the Camposanto in Pisa. Cimabue worked extensively in Pisa, painting the gargantuan Maestà now in the Louvre for the town’s Franciscan church and – at least according to Vasari – a small painting (or ‘tavolina’) of the Crucifixion, also for the Pisan friars. Cimabue died in Pisa in 1302 while at work on the apse mosaic in the cathedral there. The city also had an early and important community of Clarissan nuns at the convent of Ognissanti. So there are good arguments for a Pisan provenance.

On the other hand, the Maestro di San Martino is exclusively associated with Florence and its close environs, with surviving panels attributed to him in Florence itself, Scandicci, Pontassieve and Radda in Chianti. As Gordon was careful to acknowledge, Lasinio gathered works together in Pisa from across Tuscany, including Florence. Perhaps we should consider instead a Florentine origin for Cimabue’s diptych, with the city’s oldest Clarissan house at Monticelli, founded in 1260, a good candidate. Even before Boskovits reconstructed the Maestro di San Martino panels as a diptych, Richard Offner had already suggested in 1947 that the Crucifixion in Berlin and its related scenes may have been painted for either Monticelli or Florence’s second Clarissan house at Montedomini, founded outside the Porta San Gallo in 1311. Perhaps the expansion of the city’s Clarissan community in the 1310s spurred the copying of authoritative devotional images already in their possession. One possible scenario would see the new foundation at Montedomini asking the Maestro di San Martino for an updated version of a familiar diptych from its more established sister-house at Monticelli.

The Maestro di San Martino transformed Cimabue’s scenes into the Giottesque idiom of the 1320s, adopting the more conventional seated Christ for his version of the Mocking. But the desire of the anonymous artist and his patrons to imitate a work that would by then have been several decades old testifies to the enduring devotional efficacy and visual power of Cimabue’s narratives. This appeal should help us to locate the true significance of these carefully planned and exquisitely realised scenes. The auction house duly notes the attempts at perspective in the architectural features at right and left, but the more important quality for viewers of the time was undoubtedly the greater potential for empathy and immersion that Cimabue offered through his softened and emotive rendering of the Passion.

Thanks to the rediscovery of the Mocking of Christ, and the consolidated reconstruction of the diptych of which it is a fragment, we can now assess Cimabue’s contribution to an epochal shift in devotional practice towards the close of the 13th century that encompassed both artworks and works of devotional literature like the intensely immersive Meditations on the Life of Christ, the medieval bestseller composed for a Clarissan nun in Tuscany in around 1300 which is regarded as one of the most influential texts for religious art in the late Middle Ages. This revolution in seeing, reading and contemplation occurred in the cell or convent as much as the public space of the church and was of limited interest to Vasari, but the Mocking of Christ and its companions in London and New York do allow us to appreciate Cimabue as one of its genuine first lights.

Donal Cooper is senior lecturer in Italian Renaissance art at the University of Cambridge and a fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge.