From the October 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1985, the astronomer and science communicator Carl Sagan published Contact, a sci-fi novel about humanity’s first interaction with an advanced alien race. The vehicle for the encounter is a radio signal, transmitted from far beyond the stars, which on closer analysis turns out to contain a human television broadcast, encoded and retransmitted to initiate the ‘contact’ of the title. It is also the inspiration for the title of Jennifer L. Roberts’s book. As she explains in the final chapter, the parallel encapsulates her project: ‘Every print is a transmission from an unfamiliar world: a world of reversal, deferral, disjunction and darkness’ which ‘can only be made and known through contact’. To uncover images encoded in the signal, the characters in Sagan’s Contact must look past the obvious, analysing the information it carries in unusual ways. This is a fitting metaphor for what Roberts achieves in her brilliant and playfully erudite book. She takes the seemingly commonplace medium of print (as she says, an art form ‘both too obscure and too familiar, both beyond and beneath notice’) and transforms it into something strange and exciting.

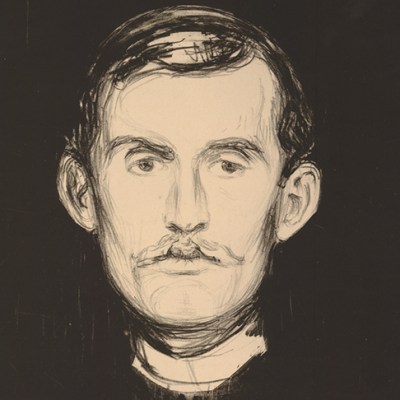

The Sudarium Displayed by Two Angels (1513), Albrecht Dürer. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Roberts’s focus is primarily on artists working in the United States and Europe after about 1960, when the methods and concepts of printmaking infiltrated the world of painting in a dramatic way. As Roberts explains, new commercial print techniques were then transforming the visual landscape, and many of the period’s most notable artists began their careers in commercial printmaking. At the same time, revived interest in traditional techniques catalysed the formation of print studios, where established artists were invited to experiment with the methods and concepts of the medium.

With this context in mind, Roberts takes aim at one of the great narratives of 20th-century art, that photography was ‘the mass medium’ of the era. In fact, she argues, the dissemination of photographs at a large scale was possible only when those photographs were translated into print: ‘much of the logic of twentieth-century photography is arguably, in the last analysis, really a logic of print.’ The images found in ‘newspapers, magazines, posters, broadsides, billboards, and art history books’ may have been photographs once, but they were transmitted as ‘printed matter, ink on paper, made on printing presses’.

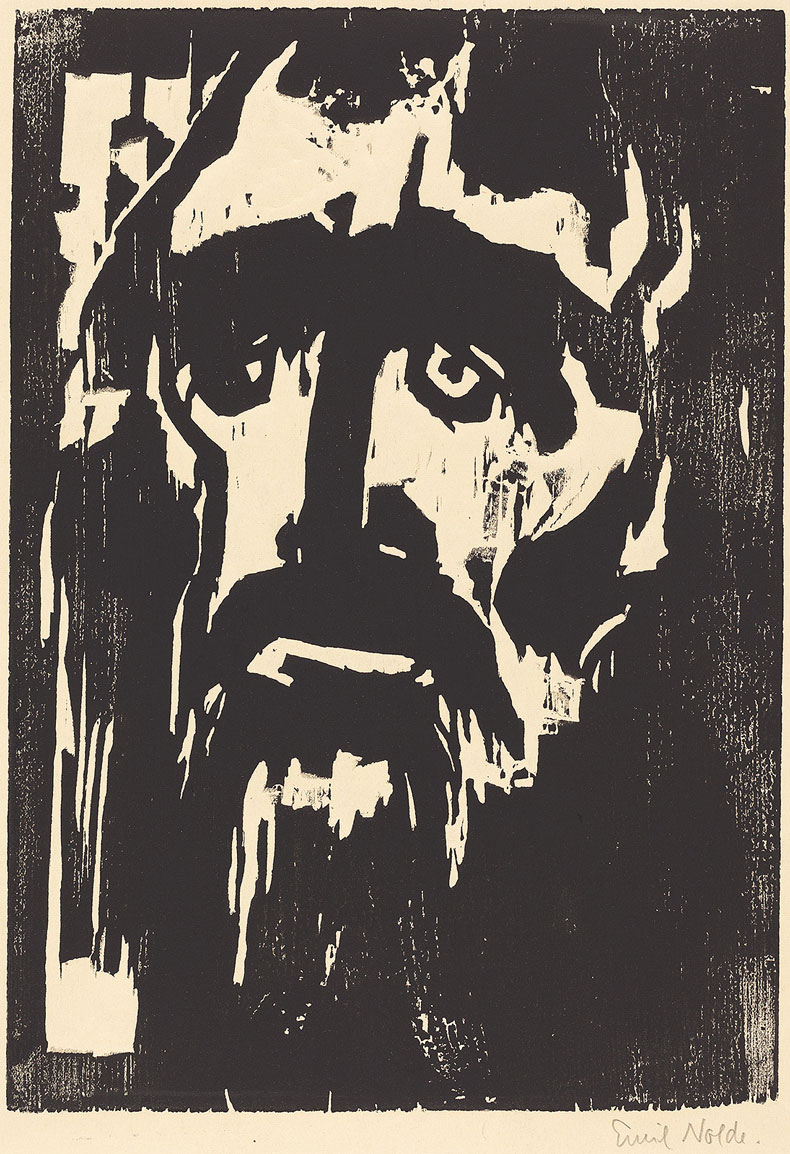

Prophet (2012), Emil Nolde. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

If our ideas are shaped by the great William Ivins Jr’s formulation that prints are, primarily, ‘exactly repeatable pictorial statements’, the fact of print’s all-pervasiveness in the 20th century may not sound like a particularly interesting or revolutionary observation. But the other great achievement of Roberts’s book is to look again at the ‘fundamental physical operations’ of printmaking. She asks: what actually happens in the press when a print is made, that ‘moment of dark and mysterious contact under intense pressure’, forever inaccessible to even the most expert printmaker? Her answers form the basis for the book’s six chapters: pressure, reversal, separation, strain, interference and alienation.

These terms are put to work, not only for their physical connotations, but also in conceptual directions, to reveal a ‘primordial grammar of print’. In the chapter ‘Pressure’, for example, she considers printmaking as based on squeezing and compressing. Her example is Robert Rauschenberg’s print sequence Hoarfrost Editions (1974), a series of multi-layered compositions made of images transferred from crumpled paper bags, newspapers and magazines, conjuring up the incredible weight of the printing process (equivalent to 600 to 1,000 pounds per square inch). But Roberts also sees, in the press’s compression of Rauschenberg’s materials, a literalist riposte to one of the major problems in art history – how to translate a three-dimensional world into a two-dimensional representation – and its traditional solution: illusionism.

Sulphur Bank (Hoarfrost) (1975), Robert Rauschenberg. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

The violence and resistance inherent in this model of image-making become the basis for one of the most thought-provoking passages in the book. This is Roberts’s analysis of the work of the African-American contemporary artist Willie Cole, specifically his series Beauties (2012) – 28 prints made from a set of battered ironing boards. Each work is given a woman’s name common in the artist’s grandmothers’ generation (Lilly, Dot, Queen) and displayed upright with its companions. Many of the women in Cole’s family worked as housekeepers and the ironing board’s domestic associations imbue it with the weight of centuries of invisible labour by Black women, alongside its other resemblances – to African shields and to the famous diagram of a transatlantic slave ship.

But Roberts’s interest in the ‘physics of print’ reveals further dimensions to Cole’s imagery. The pressure of the printing press, exerted from both above and below, causes features on the reverse of the ironing board to register through the printed front, like an X-ray. This ‘forensic power’ contributes to Cole’s general project of ‘revealing the overlooked’, but also, Roberts suggests, allows his prints to speak of ‘resistance and creative agency born from pressure’. Displayed in a vertical position, the prints have been taken from the horizontal bed of the press and resurrected with dignity, like a series of full-length, aristocratic, ancestral portraits.

On every page of this book there is an idea with the potential to transform the reader’s perspective, not only on print, but also on culture more widely. In the chapter on colour, Roberts discusses the fact that distinct colours of paint have different weights, and asks, ‘How can I make my beholding more beholden to the holding?’ The phrase is an apt summation of Roberts’s interest in ‘medium generativity’, which uses the ‘material intelligence’ inherent in print to open new modes of analysis. In a burgeoning field of art-historical studies that take the fine-grained specifics of materiality as their focus, Contact is one of the most exciting contributions to date.

From the October 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.