Like much about Picasso’s own work, the thinking behind this joyful, multifaceted exhibition is a profitable mixture of the rigorous and the exploratory. ‘Why an exhibition about Picasso and food?’ asks the Museu Picasso’s director Emmanuel Guigon in his preface to the show. Well, ‘Why not?’ On the basis that for an artist as domineeringly prolific as Picasso almost any theme could be productive, it is as good an answer as any. But the casualness of Guigon’s response is swiftly belied by the ways in which ‘Picasso’s Kitchen’ brings something to the table from almost every phase of the artist’s career. The culinary, in all its senses, proves itself a brilliant governing metaphor for a fascinating exploration of the life and work of an artist who once complained of ‘having learnt nothing except to love things and eat them alive’.

Given the prevalence of the culinary theme in Picasso’s work, it would have been a simple thing for the Museu Picasso to pull together the displays entirely from its own collections. From the myriad glasses, fruits and bottles transformed into paint in his still lives, to the real-life utensils, kitchen bric-a-brac and even bread absorbed into his sculptures and assemblages, food and its paraphernalia are just about everywhere in Picasso’s work. To do the theme justice, however, Guigon and his co-curators Claustre Rafart and Androula Michael have assembled the works here from far and wide, asking what Picasso’s kitchen can do critically and curatorially.

Menu for the Quatre Gats, Dish of the Day (c. 1900), Pablo Picasso. © Succession Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid 2018

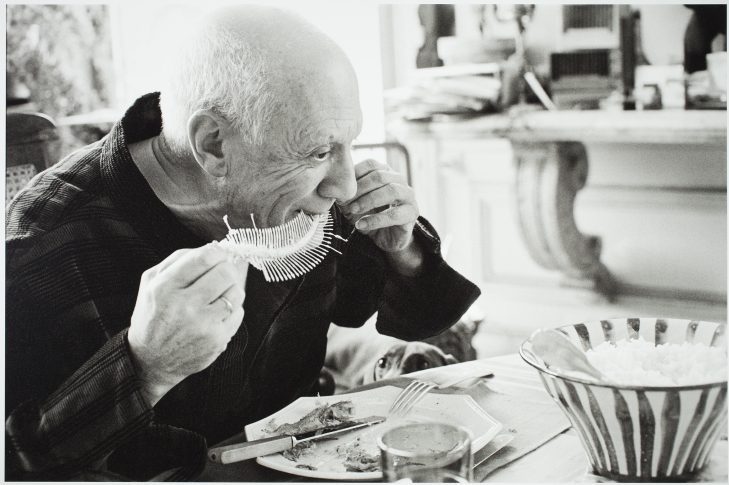

One simple answer to this question is that it provides an occasion to bring together works from every stage of Picasso’s career – some well known, many rarely seen on public display – and show the sheer range of his output. With 180 pieces on display every viewer will find their own highlights. Among mine were Picasso’s Toulouse-Lautrec-aping designs for posters and menus at Barcelona’s Els Quatre Gats bistro (c. 1900), the exquisite Blue Glass (1903), and a cardboard cutout Cuttlefish (1914) complete with googly eyes (which turn out to be an unsuspected recurring motif in Picasso’s depictions of seafood). Perhaps the triumph of the show, however, is the display of Picasso’s trompe-l’oeil ceramics from the 1950s: complete with their clay foodstuffs, they sit opposite a superb sequence of photographs by David Douglas Duncan showing Picasso delicately chewing the final scraps of flesh off a fish’s skeleton, before pressing its form into the still-wet clay of one of his dishes.

Trompe-l’oeil ceramic (Bottefarra and Eggs) (1951), Pablo Picasso. © Succession Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid 2018

The culinary provides more than a career-spanning thread for uniting works on a specific theme, though; it is also a way of posing questions about artistic practice, life, and interactions between the two. Those questions range from the quotidian impact of hunger in poverty and wartime, to the grand cruxes of personal psychology (enduringly germane to an artist whose appetites are so inseparable from his work) and artistic influence (the continuous digestion of his forebears that Picasso made central to his practice), and back to the practical acts of mixing paints and inks and firing ceramics that made so much of Picasso’s day-to-day work its own kind of cookery.

Young Boy with Lobster (1941), Pablo Picasso. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris)/Jean-Gilles Berizzi; © Succession Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid 2018

Although it is arranged chronologically, the depth of the show means that it feels less like a survey and more like an essay in which the idea of Picasso’s kitchen has been held up to the light and examined from every angle. Motifs and concerns reappear in every room, slightly changed, giving a sense of the ways in which Picasso turned the same ingredients into a whole range of different meals. A joyfully juvenile 1902 sketch of the painter Joan Ossó serving up a roast chicken while simultaneously defecating and masturbating finds echoes in the absurdist drama of Desire Caught by the Tail (1941), with its cast of sexually cavorting foodstuffs, and the same year’s nude Young Boy with Lobster. Across a sequence of prints, paintings and sketches from 1959–62, Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe is stripped like the fish bones in Duncan’s 1957 photographs, digested, and pressed into Picasso’s own work, its constituent elements of food, philosophy and nudity extracted and recombined into something else. Elsewhere, in several still lifes, feasts sit side-by-side with the traditional skulls of vanitas paintings – the old lineage of nature morte pulled over into Cubism and Picasso’s gentler post-1940s abstracts. There is, as Peter Read points out in his catalogue essay, very little distance between eros and thanatos in the kitchen; as this excellent show demonstrates there might be still less in Picasso’s.

‘Picasso’s Kitchen’ is at the Museu Picasso, Barcelona, until 30th September.