The meaning of statues, and of their destruction, has been in the news recently. Few societies had a more developed and complex habit of public statuary than ancient Rome. The Romans’ concern to establish a lasting visual record of themselves may have grown from the tradition of exhibiting wax masks of ancestors at funerals. It was expressed in the public statues of worthies and in the private tombstones of the merely well-to-do, which often featured portraits as well as wordy inscriptions about their lives and careers.

The Roman encyclopaedist Pliny, writing about portrait art, tells us something about why people wanted their likenesses to be known: ‘In my view […] there is no greater kind of happiness than that all people for all time should desire to know what kind of a man a person was.’ A little further on, he mentions a series of illustrated biographies by the earlier writer Varro: ‘Varro was the inventor of a benefit that even the gods might envy, since he not only bestowed immortality but despatched it all over the world, enabling his subjects to be ubiquitous, like the gods.’ (Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35, from a Loeb translation by H. Rackham)

The connection between image-making, ubiquity and divinity was not lost on Rome’s emperors. Both the archaeological and the literary record show us that the imperial image was a deeply significant part of life and politics in the Roman empire. Augustus and his successors swiftly came to monopolise Roman sculpture, establishing official portrait types that were copied in their thousands across the empire, and circulated on millions of coins. The emperor’s sculptural presence was a constant in civic spaces from Britain to Syria, and the hairstyles and features of the imperial court were widely imitated. Less benignly, disrespect for imperial statues came to be grounds for accusations of treason, as if the accused had slighted the emperor himself. Absurd prosecution on this basis was a common complaint made by later historians against the more paranoid and tyrannical emperors; under both Tiberius and Caracalla, for example, men supposedly found themselves in trouble for carrying a coin with the emperor’s image into a privy or brothel.

Posterity would have its revenge: one of the few checks that a polity can place on an autocrat is its capacity to shape his posthumous reputation. In Rome, effacement from the record had roots in the legal penalties for treason; it is often called damnatio memoriae by historians, though this expression is not one the Romans used. Its extent and nature could vary from case to case, and might include erasing the offender’s name from the official record, exile, prevention of a funeral or mourning, confiscation of assets with more or less lenient treatment of relatives and the destruction of any images, leaving the offender unknown to future generations. As Rome’s rule passed to emperors, versions of this practice began to apply to them as it had to earlier criminals. Within the span of the first imperial dynasty, the practice of deifying good emperors (Augustus) and condemning the memory of bad ones (Caligula, Nero) had taken hold. Sometimes damnatio was legally enforced by a vengeful senate (as happened with Domitian, Commodus and Elagabalus); sometimes, a successor emperor seems to have encouraged a convenient chiselling-out of his predecessor (Claudius prevented the Senate from officially condemning his predecessor Caligula, but ‘caused all his statues to disappear overnight’); and sometimes a popular enthusiasm for statue-toppling seems to have broken out.

A Severan inscription on the Arch of Trajan in Timgad, Algeria, in which a reference to Geta has been replaced with other text. Photo: Matthew Nicholls

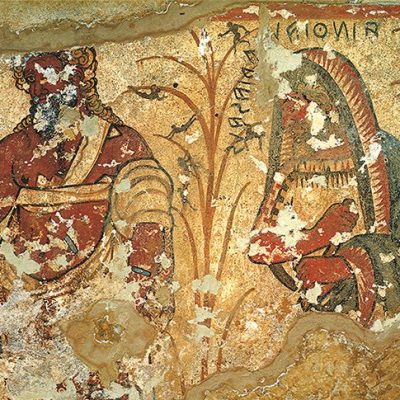

A perfect damnatio memoriae would leave no trace. In fact, though, its effects rarely seem to have been total. We have enough statues of Caligula and Nero to be able to recognise them, and their coins survive. And we can often see where damnatio has been carried out – its effects are often a rather conspicuous erasure, not a total cancelling. Portrait heads were recut to resemble the next emperor, and stand out for looking smaller than the surrounding unedited figures (look for example at Nerva in the Cancelleria Reliefs recut from his assassinated predecessor Domitian). Geta was the murdered younger brother of the emperor Caracalla, whose touchiness about the imperial image has already been mentioned. He was so systematically chiselled out of inscriptions that obviously reworked blocks of text are prominent hallmarks of epigraphy in Caracalla’s reign, while his portrait was erased with no particular attempt to disguise it. On the Arch of the Argentarii in Rome a void marks the place where Geta stood, a caduceus (Mercury’s wand) left floating in the air above his vanished head; in the famous painted tondo portrait of the Severan imperial family, his face is a grim featureless smear but his body remains. Similar acts of erasure can be seen all over the empire, so widespread that they must have been done by countless local officials and individuals, anxious to show compliance with this notoriously vengeful emperor.

Severan relief of the imperial family on the Arch of the Argentarii, Rome, with the figure of Geta removed. Photo: Diletta Menghinello/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The erasure of images was naturally a political gesture, often associated with a change of ruler or dynasty. Occasionally the last emperor’s image became a point of contention between rival successors, as with Nero (who had a surprisingly strong popular following at his death; for a while posthumous lyre-playing Neros popped up around the empire). Some images of Nero were destroyed, and others were reworked, but for a while things hung in the balance: Suetonius (in another mysterious little insight into the valency of images in the Roman world) concludes his biography of Nero by noting that for some time his followers would put his statue up on the speakers’ platform in the forum, as if he were still alive and about to come back to take revenge. Eventually the anti-Neronian faction prevailed, and in one of Rome’s most famous acts of statue-repurposing, a giant bronze statue that Nero had erected to himself was given a more seemly identity as the sun-god Helios and moved next to the amphitheatre whose popular name – Colosseum – probably derives from this colossus (later still, the statue enjoyed a brief period posing as the mad emperor Commodus, before his death brought about a further repurposing).

But as well as being a continuation of the image-making process run by and for the elites of Rome, damnatio and statue-toppling could be – as we have seen recently – a sort of public catharsis too. Here is the younger Pliny on the downfall of the emperor Domitian:

It was our delight to dash those proud faces to the ground, to smite them with the sword and savage them with the axe as if blood and agony could follow from every blow. Our transports of joy – so long deferred – were unrestrained; all sought a form of vengeance in beholding those bodies mutilated, limbs hacked in pieces, and finally that baleful, fearsome visage cast into fire, to be melted down, so that from such menacing terror something for man’s use and enjoyment should rise out of the flames. (Pliny the Younger, Panegyricus 52, from a Loeb translation by Betty Radice)

Pliny was explicitly writing here as a friend to the regime that supplanted Domitian, and was keen to excuse his own complicity in the tyrant’s reign – but this must have rung true to his contemporary audience, and calls to mind those crowds we have seen hauling down outsized Lenins and beating toppled Saddams with the soles of their shoes.

However hard emperors tried to shape their own images down the ages, and however hard their enemies tried to erase them, it seems that in the long view history is hard to fool. Caligula, Nero, Domitian, and Geta have not disappeared from the record, but the way their images were erected, changed, defaced, used and reused has become a part of their histories, often in interesting counterpoint to the official image-making efforts of their own reigns.