From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Demons stalk art’s story. Inventive torment is executed by eye-nippled lizards and fire-farting dragons in Dieric Bouts’s The Fall of the Damned (c. 1468). One of two surviving panels from the Netherlandish painter’s Last Judgement triptych, it was commissioned for Leuven’s town hall as a warning to the city’s lawmakers against corruption and vindictive judgement. The late Edo-period painter Kawanabe Kyōsai conjured demons for his outrageous political satires as well as his popular entertainments. His riotous book Pictures of One Hundred Demons (1889) is a procession of the possessed and putrefying, including the Buddha-like corpse Nuribotoke – whose eyes dangle on long gelatinous strands – and an umbrella monster.

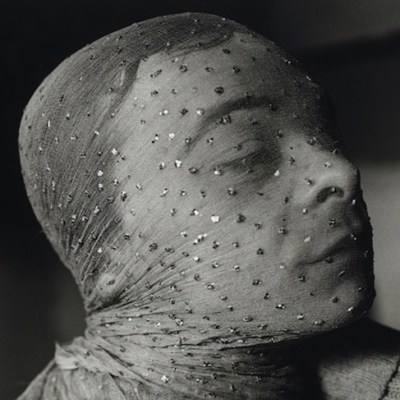

In a straightforward sense, demons offer a warning against sin or take the blame for things going awry. To those who find themselves at variance with authority, demons – and Satan in particular – also embody free-spirited rebellion, a refusal to comply. In wispy-chested drag, horns stuck to his forehead and a cigarette holder gripped between chipped front teeth, John Flowers hitches up his taffeta skirts and squats over a lavatory bowl in Peter Hujar’s portrait John Flowers (Backstage, Palm Casino Revue) (1974). In the elegiac survey ‘Eyes Open in the Dark’ at Raven Row (until 6 April), the photograph of Flowers is shown alongside portraits of others with whom Hujar felt kinship or fascination: beautiful young men, awkward intellectuals, mute farm animals, the dispossessed darlings of New York in the roach-scuttling 1970s and ’80s.

John Flowers (Backstage, Palm Casino Revue) (1974), Peter Hujar. © 2025 Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/DACS London/Pace Gallery, NY/Fraenkel Gallery, SF/Maureen Paley, London/Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich

Flowers had been a member of the delectably named San Francisco drag cabaret the Cockettes, beloved for their glittery beards, thrift-store glamour and art-school psychedelia. In New York, the extravagant punk vaudeville show Palm Casino Revue ran for 40 performances, a tinderbox of camp delights lit each evening by Flowers singing ‘Devil with the Blue Dress’ as he slunk up the aisle, appropriately attired. Hujar sees Flowers triumphant on a grubby porcelain throne, his painted grin explosive beneath the lowered forests of his lashes. Like the hermaphroditic demon Baphomet, he carried markers both male and female. He extends his throat and upper chest seductively: Monroe reincarnated in diabolical drag. In Flowers’ body fizzes a vital devilry that Hujar the outsider, the marginal, the looker-on sought out. For those who find themselves condemned and vilified in the name of a Christian God, who better to turn to than the original rebel, Satan?

The religious historian Per Faxneld’s book Satanic Feminism (2014) plots the particular susceptibility to devilish influence that women were believed to have. Women were weak-willed, credulous, and driven by their carnal appetites. Just look at Eve, who was beguiled in the Garden of Eden by Satan in the guise of a serpent. In the florid imagination of witch-hunters in the early modern period, Satan’s seduction of Eve established a pattern of devilish influence that was replicated in acts of demonic and animal congress during witches’ sabbaths.

Stories are always available for retelling, and myths open to new interpretation, and so it has proved with the Fall. In counter mythology, Satan’s invitation that Eve and her husband eat from the tree of knowledge and ‘be as gods’ is reimagined as an act of liberation.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, sympathy for the devil became totemic for socialists, artists and writers who placed themselves beyond conventional morality, whether in their sexuality, their politics, their spiritual sensibilities or their rejection of bodily shame. Reading John Milton’s Paradise Lost, William Blake observed the poet’s unfettered delight in language when treating of matters hellish, and his comparative restraint in describing the heavenly and divine. Milton ‘was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it’, Blake decided. (Apparently, the devil not only has the best tunes, but also the best iambic pentameter.)

Act One (2024; detail), Citra Sasmita. © the artist

For women fighting for rights to education, this fable of a patriarchal God who forbids access to knowledge under threat of death, and a subversive spirit who places it within reach, has an intoxicating resonance. Feminists from the late 19th century onwards have also taken the figure of Lilith – Adam’s rebel first wife, and a demon of Jewish mythology – as their own. In feminist counter-myths of Lilith, she was formed, like Adam, from dust, and saw herself as her husband’s equal, refusing to lie beneath him or to accept his dominance. For this she was banished from Eden, and her place by Adam’s side taken by Eve. Against the backdrop of a conservative, anti-feminist turn, particularly in US politics, the demon Lilith once more stalks the work of women artists.

Citra Sasmita has drawn freely from sources ranging from Dante’s Inferno to Arthur Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell (1873), the Mahabharata and Indonesian mythology in composing her epic ‘Into Eternal Land’ (at the Curve, Barbican, until 21 April), a visual creation story that moves from primal chaos through to spiritual elevation. The heart of ‘Into Eternal Land’ is a sequence of painted Kamasan scrolls and embroidered banners. There are winged heads recalling Christian seraphim, decapitated figures spouting nourishing blood like the Hindu goddess Chhinnamasta, there are trees sprouting from wounds, divided heads, battles, births, miracles and, of course, demons. In place of the male heroes of the source texts, all Sasmita’s figures – good and evil – are female, making her choice of historic Indonesian media a calculated subversion. It is an empowering rebel mythology, cloaked in the garb of tradition.

From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.