New Orleans is undergoing a monumental change, albeit one beset by stops and starts. Last month, under cover of darkness and armed guard, contractors furtively dismantled a granite obelisk dedicated to the 1874 Battle of Liberty Place. Heckled by a couple of staunch objectors, their removal of the piece – long condemned by officials and residents alike for its overt celebration of white supremacy – was considerably more successful than their attempts, on Monday evening of last week, to do away with the city’s bronze statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis from his prominent Mid-City spot. As anti-monument protestors clashed with Davis supporters on site – Confederate flags conspicuous among Davis’s advocates – the authorities decided to postpone proceedings. Thanks to his followers, Jefferson Davis will have one last stand.

There has been renewed scrutiny and heated public debate over the place of the South’s Confederate and white supremacist legacy in present-day America. The New Orleans City Council’s plan to dismantle a total of four monuments represents the most radical approach yet to the ongoing problem of Lost Cause memory and the racial violence it is founded on. Yet while the move will irrevocably alter the city’s landscape – revising a topography of oppression to reflect the values of a modern, racially diverse community – the City Council’s intervention remains controversial among Confederate sympathisers and public historians, both.

In the case of the Liberty Place monument, the Council’s stance is hard to fault. Erected in 1891, the obelisk celebrates an insurrection launched by the Crescent City White League in 1874. Largely comprised of Confederate veterans, the League’s violent coup sought to depose elected northern Republicans and overthrow their attempts to bring political stability and African-American rights to the postwar South. Before Federal troops restored order, the White League’s 5,000 militants held the armory, state house, and downtown New Orleans for three days: in commemorating their act, the southern Democrats of the city government who erected the monument 17 years later ultimately celebrated what historian Kevin M. Levin has recently called ‘a violent act of terrorism’. Inscribed on its side is a paean to ‘white supremacy in the South’. In the years following its construction, the monument became a rallying site for the Ku Klux Klan.

The Liberty Place monument in New Orleans was removed on 24 April and is to be placed in a museum. Photo: Infrogmation/Wikimedia Commons (used under Creative Commons licence [CC. BY 3.0])

It seems something of an ethical duty to question, as the New Orleans City Council have done, the place such reminders of a morally reprehensible past can have in a civic society looking to nurture inclusion, tolerance, and social responsibility. In voting to remove the obelisk, as well as statues of Davis, and Generals Robert E. Lee and P.G.T. Beauregard, the City Council has arguably taken an active step to acknowledge and advance the change in social values that has taken place since the 1890s. Its plan to resituate the monuments in museums, where they can be displayed and recontextualised, certainly seeks to mark them, and the beliefs they represent, as historical artefacts.

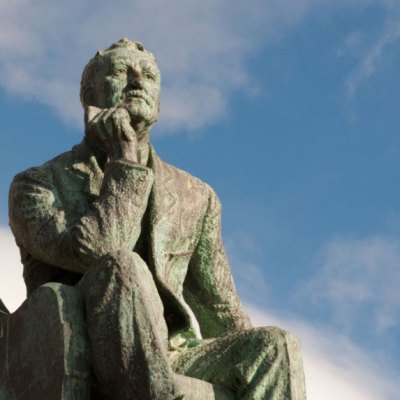

Indeed, the museum move has proven a popular and effective means of dealing with Confederate monuments elsewhere. The University of Texas at Austin recently relocated a bronze sculpture of Jefferson Davis by Italian artist Pompeo Coppini to its new Briscoe Center for American History, removing it from the South Mall where it had long been the subject of complaints from the academic community. Recognising the statue’s status as a work of art, and one to be learned from, the Briscoe Center’s exhibit says more about the sculpture’s history than Davis’s, dismantling Confederate ideology as it does so, and actively rendering it the stuff of the past.

Of course, as flag-waving protestors demonstrate, the Confederate legacy isn’t quite as easy to relegate to history as the instigators of these projects might hope. The racial and social conflicts raised by that past are still, undoubtedly and regrettably, present. It has been suggested that moving monuments from their original public settings is tantamount to erasing history (especially when they are moved to storage rather than re-displayed), and there is also a case to be made that recontextualising such monuments in situ might prove more productive, for the community as a whole, than relocating them. Numerous public historians have pointed out the potential benefits of using Confederate monuments to generate public conversations and collective projects, which might work to produce built responses to them.

As well as enabling a democratic discussion about that past among all residents – not solely government officials – the creation of new plaques placing statues in historical context, and more ambitious approaches to recontextualisation, could prove a socially significant means of enabling civic empowerment and symbolically reclaiming the South’s historical landscape. Some public historians have gone as far as suggesting that new monuments to slaves or Union troops be erected as modern counter-memorials in the vein of Kristen Visbal’s Fearless Girl, which was placed opposite Wall Street’s Charging Bull to celebrate International Women’s Day back in March. Modern comments in granite and bronze could begin to affirm the South’s cultural and civic landscape as one of conversation, rather than one of oppression, or one completely void of any references to its troubled past.

Either way, current events in New Orleans may well herald a widespread change in policy towards the monumental remainders of the Confederate legacy.