From the January 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Ronnie’s “evil empire” attitude has to go. Gorbachev’s Aquarian planet is in such harmony with Ronnie’s, you’ll see […] They’ll share a vision.’ So wrote Californian astrologer Joan Quigley in her 1990 memoir, which has pride of place in a new exhibition at the Bodleian in Oxford, ‘Oracles, Omens and Answers’ (until 27 April). In the preceding decade, a mini-scandal had erupted in the Reagan White House when it was revealed that first lady Nancy Reagan regularly consulted Quigley. Some claimed that these consultations affected only presidential scheduling. For others however, not least Quigley, US-USSR rapprochement was literally written in the stars.

The Bodleian exhibition juxtaposes Quigley’s memoir with a beautifully illuminated 14th-century geomantic treatise produced ‘for the solace’ of Richard II. Geomancy – a form of divination from patterns seen in earth – was an ancient practice that began to take on astrological associations in the Middle Ages following its transmission from the Middle East to Europe via texts such as that of Petrus de Apono, which features in the Bodleian manuscript. In the case of both Richard II and Ronald Reagan, the leaders were reportedly using divinatory practices as road maps by which to orientate themselves and their policies.

This was nothing new – and certainly not confined to politicians. From astrology and tarot to geomancy and spider divination, cultures all over the world have, for millennia, turned to divinatory practices to attempt to answer questions big and small, personal and global. Although each of these practices continuously attracts a finite group of devotees, their wider popularity has tended to coincide with national and global turmoil. It’s no wonder, therefore, that after years of pandemic, doom-scrolling and increasing geopolitical uncertainty, the esoteric arts are once more holding sway in the public consciousness. Besides the Bodleian exhibition, a recent show at the Getty in Los Angeles and an upcoming exhibition at the Warburg Institute in London turn the curatorial spotlight on divination as an artistic as well as cultural practice. For alongside the millennia-old quest for answers, divination has often led to artistic innovation – whether that be as inspiration for artists or as vessels for semantic systems. The imagery used often reflects and refracts the wider social, cultural and political concerns of the age.

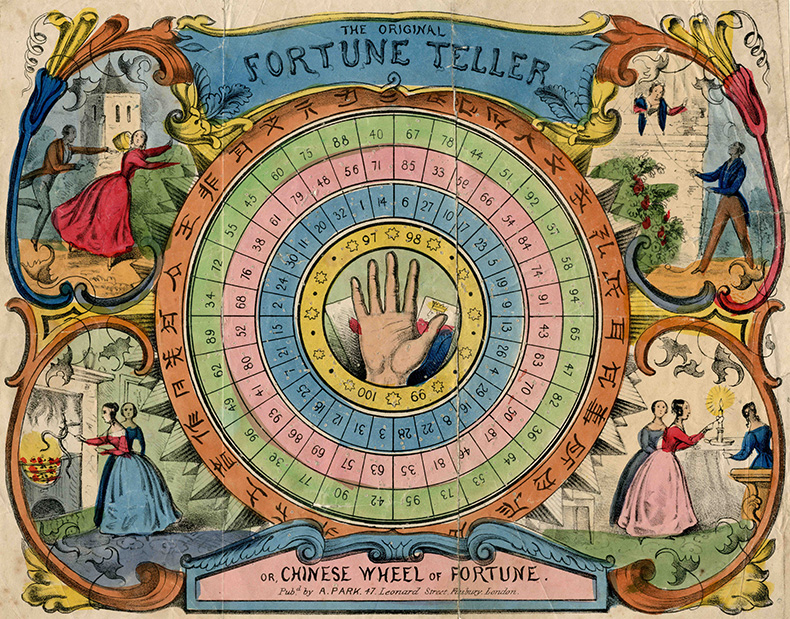

The Original Fortune Teller, or, Chinese Wheel of Fortune (19th century), A. Park. Photo: © The Bodleian Libraries

In one respect, the earliest forms of divination were far removed from aesthetic concerns. Oracle bones, used in China in the 12th to 10th centuries BC, were pieces of ox scapulae or turtle plastrons (the lower shell). Diviners would apply heated metal rods to the bone or shell until it cracked and interpret the resulting patterns. Characters inscribed on these bones are the earliest written records that survive from East Asia. In 2nd-century BC Mesopotamia, cuneiform tablets recorded the details of bird divination. Ancient Mesopotamian bird divination was a form of haruspicy, also known as extispicy – reading the entrails of sacrificed animals. Signs present in, usually, the liver were believed to be communications from the assembled gods regarding the querent’s request. These were interpreted by diviners, who calculated the number of positive and negative signs to give a response. Recording both the request and the signs on a clay tablet was an important part of the divinatory process. Artefacts associated with both the Chinese and Mesopotamian practices are displayed in the Bodleian exhibition.

In Europe, divination flourished in ancient Greece and Rome, serving as a bridge between the human and the divine. In Greece, divination shaped decisions in both public and private spheres. The Oracle of Delphi, dedicated to Apollo, was among the most celebrated sources of divine insight. Pilgrims sought answers from priestesses, who were believed to channel the god’s voice via often cryptic prophecies. The Romans adopted and expanded Greek and Etruscan divinatory practices, which also included oneiromancy (dream interpretation), augury (where seers analysed natural phenomena, such as bird behaviour, to dis-cern omens) and haruspicy. Divination was quasi-institutionalised, reflecting Rome’s belief in the gods’ active role in its fate. These rituals were vital to maintaining the pax deorum, or peace with the gods, that allowed the Republic, and then Empire, to prosper.

Another type of divination of vital importance in the Roman world was astrology. Its origins can be traced back to ancient Babylon, where the earliest known astrological records have been dated to the 2nd millennium BC. From there it spread to Egypt. The Greeks added to the development of astrology in Europe, notably through Ptolemy’s mid 2nd century astrological treatise Tetrabiblos, which remained influential for centuries. It was believed that the positions of the planets at the moment of a person’s birth could shape their personality, influence their destiny and even predict their future. From this came the horoscope. From Greece, astrology made its way to the Roman Empire, where it was widely used. Roman emperors, in particular, frequently sought the advice of astrologers. Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, often used astrology to affirm that his extraordinary reign was written in the stars, adopting the star sign with which he identified (Capricorn) as a symbol, and working with a personal astrologer.

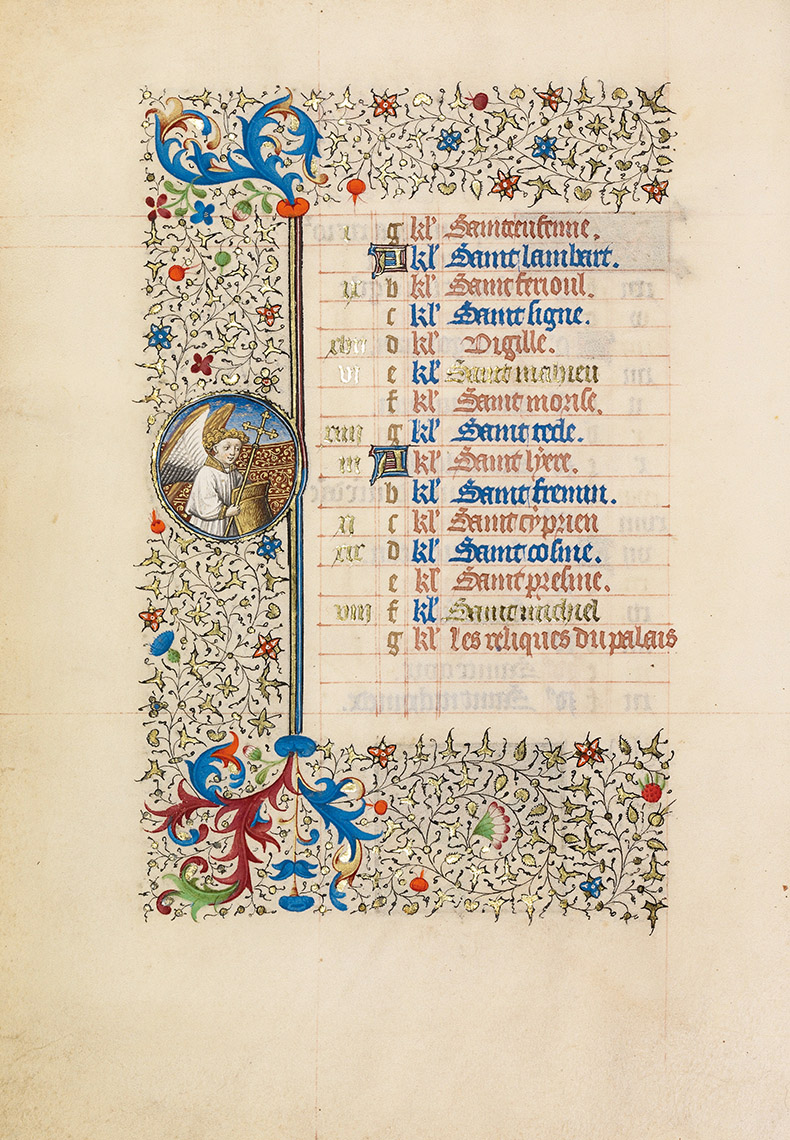

Page from a Book of Hours, c. 1440-50, workshop of the Bedford Master. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The ancient world was also when astrological imagery began to be employed in the wider decorative arts such as on mosaics, tombs and bas-reliefs. However, it was in the Middle Ages that the visual really took off. Astrological imagery began to underpin – consciously or unconsciously – broader cultural production, thus becoming increasingly embedded in the public imagination, as the J. Paul Getty Museum’s recent exhibition ‘Rising Signs: The Medieval Science of Astrology’ (1 October 2024–5 January) explored.

Featuring examples from its large collection of manuscripts, the exhibition was divided into four sections looking at the medieval history of the zodiac and the uses of astrology during the period. The spread of astrology into broader life via artistic means took it out of the realm of specialist, arcane practice and transformed it into a common language.

The way in which astrology was conceived of artistically both stemmed from and was reinforced by its integration into activities of vital importance for medieval daily life, including weather forecasting, agricultural activities and health. The names of some days of the week in many European languages are based on celestial bodies. Astrology was combined with Christian beliefs to form cycles that governed the hours, days and months. The phases of the moon and the signs of the zodiac were incorporated into manuscripts of Psalters and Books of Hours – devotional and liturgical texts designed to guide individuals through daily prayer at specific times – and into some decorative cycles depicting the Labours of the Months, which illustrated common rural activities associated with each month of the year. The Getty exhibition featured several fine examples of early Psalters and Books of Hours. One page from a French Book of Hours produced in the first half of the 15th century by the workshop of the Bedford Master shows the calendar page for September with an elaborate foliate border featuring a roundel showing St Michael (Michelmas falls in September). The opposite page illustrates October. Here the same border is punctuated by a vignette showing a man sowing (one of the traditional monthly activities for October) and, in a roundel directly opposite to that of St Michael, a scorpion for the zodiac sign Scorpio. Such a juxtaposition deftly illustrates how artistic production interwove Christian devotion, nature and astrology.

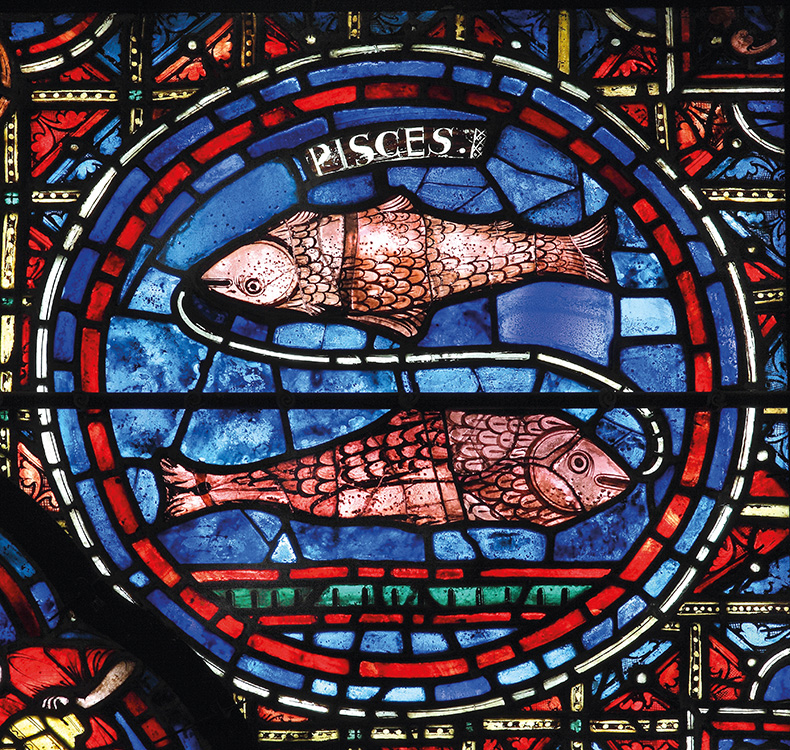

The Labours of the Month were not confined to private devotions. They also often featured in the decoration of churches and cathedrals – with notable examples including inlaid floor medallions in the Trinity Chapel at Canterbury Cathedral (close to the site of Thomas Becket’s tomb), stained glass windows at Chartres Cathedral and on the facade of the Cathedral of St Martin in Lucca. These cycles visually conveyed the medieval belief in the harmony between the earthly and the cosmic. The visual depiction of astrological symbolism in manuals and public art projects that were designed to be used, seen and interpreted by wide audiences ensured it was experienced by broad social groupings.

A detail from a stained glass window at Chartres Cathedral, France, which features signs of the zodiac. Photo: © Manuel Cohen

Just as astrology was believed to shape human life and nature throughout the year, it was also thought to exert a profound influence over sickness and health, the focus of the third section of the Getty exhibition. Zodiac Man (or, less commonly, woman), first seen in the 11th century, was a symbolic representation in which the human body is divided into sections corresponding to the zodiac signs, with each part linked to specific bodily functions or ailments. Treatment plans for illness or injury would also consider the patient’s ruling sign and the time of year. The Getty exhibition also includes an intriguing Zodiac Skeleton, an early 16th-century iteration of the medieval Zodiac Man, the frontispiece of a printed French Book of Hours.

In all these medieval contexts, the use of astrological images allowed the viewer to journey through a wide skein of personal and global events. It’s no wonder, therefore, that Aby Warburg, who conceived of his Bilderatlas (image atlas) as a way to map the evolution of ideas and human experience across time and space via the cultural and historical connections between images, would have been interested in astrology. Now the London research institute that bears Warburg’s name hosts a new exhibition on another form of divination, but one very much linked to astrology: tarot.

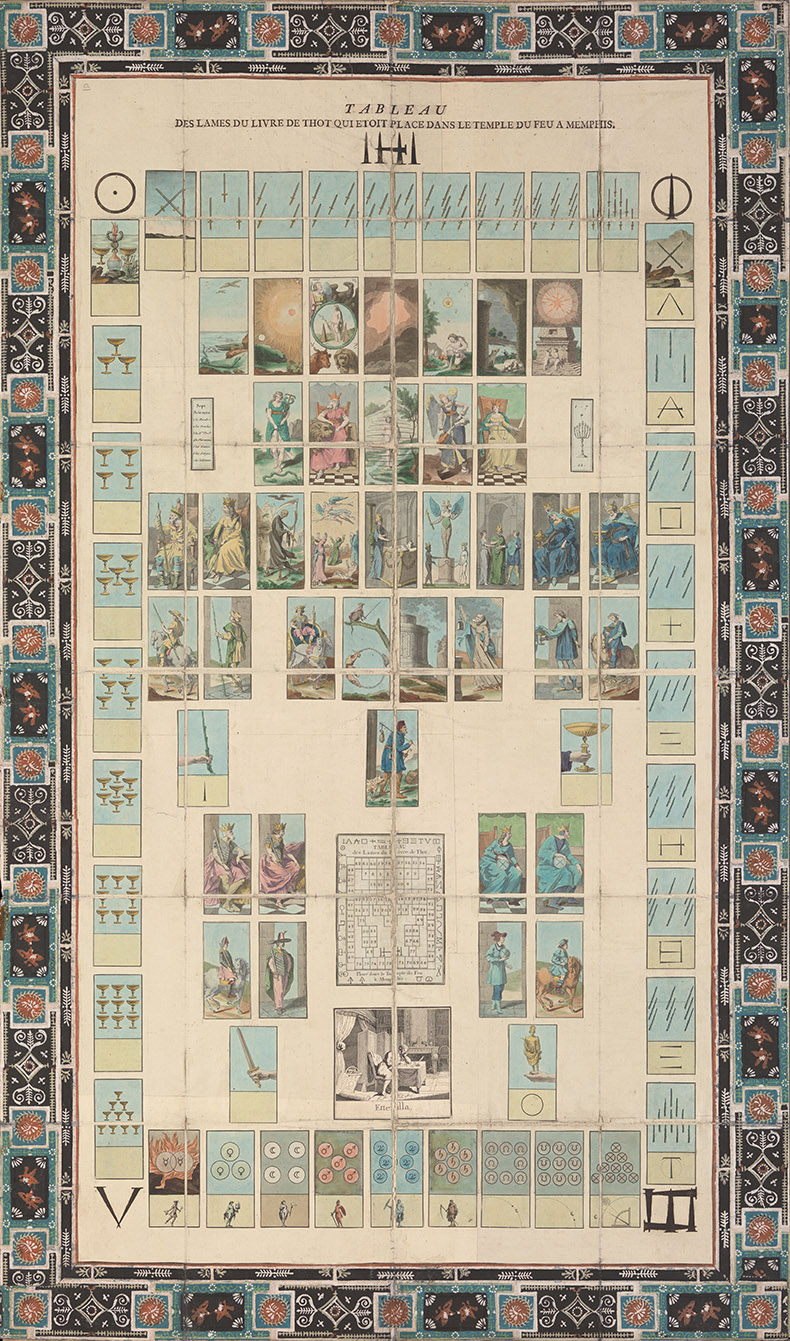

The practice originated as a 15th-century Italian card game at the Milanese and Ferrarese courts, with four suits and 22 trump cards. Early examples, such as the exquisite Visconti Tarot, were hand-painted by skilled artists and adorned with gold leaf – a selection of these will be on display in ‘Tarot – Origins & Afterlives’ (31 January–30 April). It was only in the 18th century that it took on divinatory connotations, when occultists such as Antoine Court de Gébelin, Éliphas Lévi and Jean-Baptiste Alliette (Etteilla) reimagined it as a repository of ancient mystical wisdom. This recontextualisation culminated in the creation of the Rider-Waite-Smith deck in 1909, a collaboration between the scholar Arthur Edward Waite and the artist Pamela Colman Smith. The Warburg exhibition promises to present new discoveries, physical and theoretical, explaining Warburg’s intertwined interests in astrology and tarot. With many of the objects being shown for the first time in the UK, visitors can also expect to see some of the earliest known examples of tarot cards, Etteilla’s fortune-telling deck, Austin Osman Spare’s hand-painted deck, Suzanne Treister’s HEXEN projects, and a selection of Frieda Harris’s paintings for the Thoth Tarot, a collaboration with occultist Aleister Crowley in the 1930s and ’40s.

The Tarot, in the form of leaves of the book of Thoth place in the Temple of Fire at Memphis, Egypt, c. (1780–89), J. B. Aliette/Etteilla. Wellcome Collection, London

Tarot, particularly the archetypes of the Major Arcana – the Fool, the Lovers, Death etc. – has provided rich inspiration over the centuries for artists as disparate as Dalí and Niki de Saint-Phalle, whose monumental colourful sculptures have frolicked through her Tarot Garden in Pescia Fiorentina (Tuscany) since 1998. Most evident from the Warburg exhibition, however, is the way in which tarot cards are profound carriers of symbols, often displaying the preoccupations of the age. Harris’s paintings, created to distil Crowley’s life’s work into tarot deck form, were created as Europe teetered on the brink of the Second World War. Her iteration of Death appears menacing, mechanical and martial. The Warburg exhibition culminates by transforming the Library of Exile (donated to the Institute by its creator, Edmund de Waal) into a Tarotkammer. On the shelves are recent and contemporary decks created by artists as a way of summarising, in visual form, varied important themes and socio-political causes. These include racial representation (Courtney Alexander’s melanated tarot deck), the HIV/AIDS epidemic (John Walter’s Alien Sex Club tarot that interrogates concepts of virality) and social equality (Katie Anderson’s Barrow tarot). As such the visual aspect takes on a didactic function, with each tarot deck becoming symbolic of something greater than just a divinatory tool.

Alexander’s Dust II Onyx deck is a case in point. While Alexander does give tarot readings using the deck, ‘to honour your unique spiritual and personal path’, according to her website, and has an associated guidebook to lead interested parties on their own journeys with the deck, it is also a way of challenging the traditional Eurocentric imagery often found in classic tarot decks. Representations of Alexander’s mixed-media collage paintings decorate the cards, highlighting ‘cultural myths, symbolism, history and icons within the Black Diaspora’.

The exhibitions at the Bodleian, Getty and Warburg Institute indicate that divinatory practices such as astrology and tarot have never been static, but instead are living reflections of the ages in which they operate. The visual aspect of divination offers those using it more than simply an answer – it offers a way of seeing and interpreting a world in constant flux. After all, sometimes the most profound answers lie not in what we see, but in the way we see it.

‘Oracles, Omens and Answers’ is at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, until 27 April; ‘Tarot – Origins & Afterlives’ is at the Warburg Institute, London, from 31 January–30 April.

From the January 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.