Many women artists have been reappraised in the last decade and exhibitions and books have sought to remove some from the shadow of the men with whom they were involved romantically (Lee Krasner; Dora Maar). But what are we to make of a woman who was desperate to disappear? A figure who further complicates the feminist endeavour of rescuing overlooked artists because she was in a relationship with another woman who took the spotlight? Meet Dorothy Hepworth, whose paintings and drawings were accredited to her romantic and artistic partner Patricia Preece until they both died.

Who doesn’t like an exhibition laced with intrigue? The question of why Hepworth would do this hangs, unanswered, over this slim but fascinating retrospective, the largest of its kind since their deaths, which includes many newly discovered works. Neither Hepworth nor Preece give a definitive explanation in their joint diary entries or in the letters that line the vitrines.

Photograph of Dorothy Hepworth (left) and Patricia Preece (right), taken in the early 1920s. © Dorothy Hepworth Estate

Time to play detective. From their years at the Slade at the end of the First World War (when more women were admitted to the school due to conscription), we compare Preece’s hazy, derivative figure studies with Hepworth’s confident, sharp lines and consider their degree certificates (a pass for Preece; first-class honours for Hepworth). One Hepworth sketch stands out: a sophisticated self-portrait in which Hepworth’s eyes warily dart to the side, her face humming with anxiety. Meanwhile in a photograph of the pair, Preece is posing nonchalantly, her arm resting on Hepworth’s shoulder while Hepworth clasps her hands in front of her.

After four years at the Académie Colarossi in the 1920s, Hepworth’s signature is replaced by that of Preece’s and when Preece later presented ‘her’ paintings to Roger Fry, and received his endorsement, there was no turning back. As other members of the Bloomsbury circle began to champion Preece, did it become too difficult for Preece and Hepworth to reveal their hoax? Or did the arrangement suit both of their characters: the outspoken Preece provided the charisma and the letter-writing, marketing, negotiating and organisational gusto. Meanwhile, the more reserved Hepworth painted. Afterall, how could a woman in the early 20th century survive as an artist without a knack for self-promotion as well as talent?

Still Life (n.d.), Dorothy Hepworth. Courtesy Court Gallery; © Dorothy Hepworth Estate

After the Wall Street crash deprived Hepworth of her father’s financial support, the pair, living in the Berkshire village of Cookham, depended on income from their work together and any other sources they could find. One such was Stanley Spencer, whose obsession with Preece led to paid sittings and later marriage. The pair never lived together and Hepworth even accompanied Preece on the honeymoon. The marriage may have provided financial security but Spencer, after realising Patricia was deeply attached to Hepworth, spread word of their relationship (and in a letter to a friend remarked that he’d never seen Preece paint). Unsurprisingly the art establishment rallied around Spencer and, after the Second World War his reputation grew, while that of ‘Preece’ declined. In the 1980s and ’90s, as Spencer’s work was canonised, there was even a play about the love triangle between him, Preece and his first wife Hilda Carline – with Preece cast as an exploitative lesbian. In the ’90s, Hepworth’s work was championed by Spencer expert Michael Dickens with an exhibition titled ‘The Art of Dorothy Hepworth, a.k.a. Patricia Preece’.

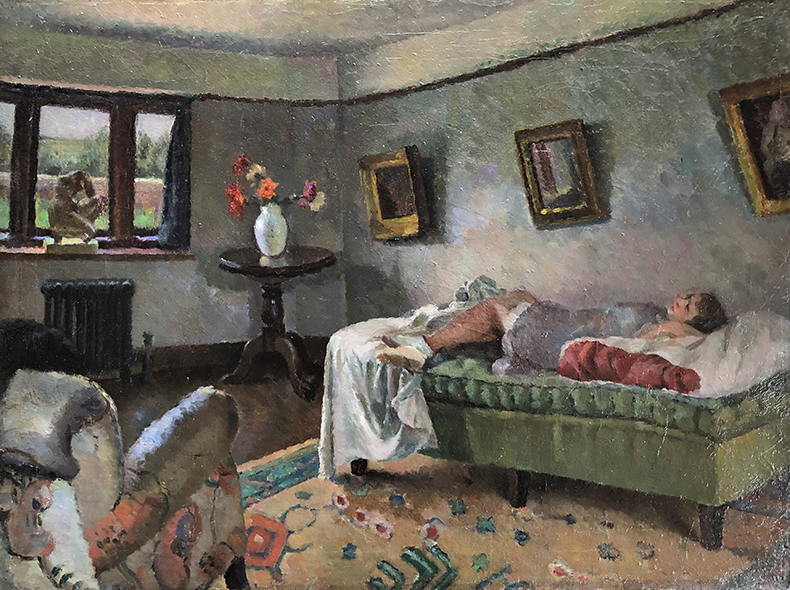

The Charleston show isn’t interested in soap opera, but if anyone is rescued from the villain/victim dichotomy that most accounts so far have favoured, it is Preece. Throughout the exhibition, the art is presented as that from a partnership and wall texts credit both as artists. Hepworth’s studies of Preece attest to a mutual love and eroticism between the two that is missing in Preece’s gaze in the fleshy contemplation of her by Spencer that is also on display.

The Green Divan (n.d.), Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece. Private collection. Courtesy Court Gallery; © Dorothy Hepworth Estate

Did Hepworth have any regrets? Preece’s talent was celebrated with solo exhibitions in 1936 and 1938 and, Hepworth couldn’t paint acquaintances or famous people (letters show that Virginia Woolf was keen for Preece to paint composer Ethel Smyth), who would have discovered who really held the paintbrush in the relationship. Hepworth did paint commercially-friendly still lives (Vanessa Bell urged her to paint more of them, in brighter colours, in order to sell more), but her strength lay in portraiture. There her muted, sombre palette and her unusual compositions, with her subjects captured deep in thought, created an intense and uneasy atmosphere. As Clive Bell remarked in 1938 of Hepworth’s painting style: ‘She is Nordic rather than Latin, psychological rather than decorative.’ However Hepworth could paint only Preece or local villagers who didn’t care who was behind the canvas or know anyone in artistic circles to tell if they did. But, as a wonderful collection of Hepworth’s portraits of Cookham resident’s shows, she was more interested in capturing ordinary lives in a dispassionate and detached manner.

Photos of Hepworth by Preece posing with her paintings are one of the highlights of the show – and perhaps proof that they both wanted a record of Hepworth’s artistry to be known one day. In the 12 years after Preece’s death, however, Hepworth continued to sign her paintings as Preece – a bond that joined them even as they were separated. Together, Hepworth and Preece created a room of their own, one that allowed for art and love to thrive, which was no insignificant feat for two women of their time.

Girl in Blue (n.d.), Dorothy Hepworth. Private collection; © Dorothy Hepworth Estate

‘Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece: an untold story’ is at Charleston, Lewes, until 8 September. An accompanying book, The Secret Art of Dorothy Hepworth AKA Patricia Preece, by Denys J. Wilcox is published by Court Gallery.