From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

There’s a memorable passage in Samuel Beckett’s Molloy (1951), in which the vagrant narrator of the novel’s first section ruminates on his method of sucking stones. The process of transferring 16 pebbles between his two pockets and mouth and back again, so as to suck each stone in a consistent order, is a puzzle that proves irresolvable, inevitably defeating him. ‘They all tasted exactly the same,’ he finally admits. He determines to keep only one stone, ‘which of course I soon lost, or threw away, or gave away, or swallowed.’

Holding pebbles in the mouth is not as outlandish as it may sound. People from many cultures have done so, particularly in hot, dry climates, as they have sought to quicken their saliva glands in order to fend off thirst. Swallowing stones is a bad idea, of course. Like many bad ideas, Western medicine has a name for it: lithophagia, a type of pica, which is the predilection for chowing down on stuff that you are not supposed to eat.

The folly of eating stone has not stopped people from seeing food in it. The suggestion has long been there in cipollino marble, its name taken by turns to evoke the colour of onions, the stratified composition of the stone or its particular frailty (John Ruskin wrote of ‘the intended sense of a stone splitting into concentric rings, like an onion’). No doubt the potential was there, too, in the cube of jasper that a Qing dynasty artist carved, drilled and dyed to create the celebrated ‘Meat-shaped Stone’, now in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei: a little lithic altar of pork belly, hardstone rendered as soft fat.

Transforming substance into familiar forms is part of the business of sculpture; discerning those forms in geological matter might imply that the Earth, whether by accident or design, is a vast sculpture in its own right. (In fact, as Fabio Barry describes in Painting with Stone, until the advent of modern geology it was often conceived in terms of a divine painting.) And when the patterns or formations of stone resemble food, we are readily corralled into the realms of comedy and curiosity. In a recent exhibition at Cromwell Place, London, the dealership Oliver Hoare displayed a wedge of white chalcedony, threaded with dark-green pyrolusite, as ‘A Slab of Stilton’. Its verisimilitude baited this viewer, at least, into sniffing the stone in a bid to disqualify its appearance.

The late Jimmie Durham revelled in this sort of false identification. In a series of installations called The Dangers of Petrification, begun in the mid 1990s, the American artist placed pebbles and rock samples in vitrines, with handwritten labels spelling out the fossilised foodstuffs that the objects resembled: ‘petrified pecorino’, ‘petrified melon’, ‘petrified poppy-seed dinner roll’. The effect was somewhere between a geological display and a buffet, with some of the rocks presented on plates or chopping boards. A few were accompanied by knives, their blades taunted by food they could never hope to cut.

For Durham, I sense, this was mischief with a serious intention. Many of his works satirised prevailing classificatory systems – in this case, those of natural history museums – in an openness to alternative modes of organising of the world. The title, The Dangers of Petrification, suggests that risk is inherent as things harden up, not so much as the slow time of geology turns them to stone but in a metaphorical sense, as their definitions become fixed in place. Durham drew further attention to this through the inconclusiveness of some of his labels: a slice of red marble described as ‘petrified pizza or Portuguese sausage’, a small flint as a ‘petrified bon bon of indeterminate flavour’.

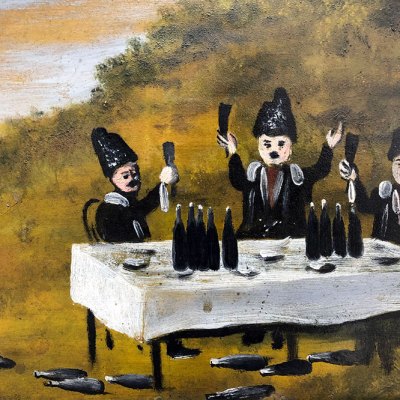

Part of the stony spread at the ‘Rock Food Table’. Courtesy Julia Toombs/East Texas Gem and Mineral Society

In one of the two vitrines of The Dangers of Petrification II (1998–2007), a note reads: ‘[Al]most anything, given the proper conditions and enough time, can turn to stone.’ For all their irony, these works also propose wonder, of the magic of durational natural processes that may be apprehensible but are hard to comprehend. They let us dream that even what is eminently perishable may be preserved. From that perspective, Durham’s vitrines have close kin in the Rock Food Table, a display owned by the East Texas Gem and Mineral Society (ETGMS). Starting in 1983, the Texan ‘rockhounds’ Bill and Lois Pattillo gathered samples of rocks and minerals that resembled items of food, displaying them to fellow enthusiasts on a table set for dinner. Touring the table to specialist shows across the United States, through donations, acquisitions and their own finds they amassed hundreds of objects: cheese in honey calcite, slug-pearl hominy, alabaster bacon, agate bubble gum. There are now more than 30 potatoes, club secretary Julia Toombs tells me, and nearly two dozen eggs.

In practice this collection is organised into three tables, laid respectively for dinner, dessert and breakfast. Each table represents meals for which individual diners are served different dishes – as though catering for a large, fussy family of stone eaters, in which one sibling insists on hamburger, another on chicken, a third on pork chop. The whole thing is deliciously exuberant, a monument to both the wit of its creators and the geological plenitude that fascinated them. It will next be displayed at the society’s annual show at the Tyler Rose Garden Center, Texas, from 21–23 January. Visitors are not permitted to touch the rock foods, let alone taste them.

From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.