If you’re watching Wicked this weekend, starring Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo as student witches Glinda and Elphaba, you’ll be stepping into a familiar, if fantastical, scene. The screen adaptation of the hit stage musical is a prequel of sorts to The Wizard of Oz (1939), drawing on that film’s Technicolour world to tell a story that unfolded long before Dorothy set her ruby-clad foot on the Yellow Brick Road.

This is hallowed cinematic ground. The classic film was no picnic to make: there was a revolving door of writers and directors, a giant cast – including scores of actors dressed as Munchkins – and a budget approaching $3m (around $68m today). But once seen, the gleaming heights of the Emerald City, the sheer scale and intense hues of Oz, are never forgotten. Watching the film is like walking into a work of art.

The man who painted Oz was a Scottish artist named George Gibson (1904–2001). At the time, he received no credit for his work on the film, but his designs define some of Hollywood’s most beautiful movies. Born in Edinburgh in 1904 and raised in Moray in the north of the country, he trained at the Edinburgh College of Art and the Glasgow School of Art while doing part-time work as a scenic painter in theatres. After moving to the United States to find work in 1930, he got his first film job at Fox Studios, where he worked on the historical epic Cavalcade (Frank Lloyd, 1933). He was hired by MGM as a storyboard illustrator in 1934, and by 1938 he was running the studio’s scenic design department.

A still from Brigadoon (dir. Vincente Minnelli, 1954). Photo: Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

Which is how he found himself creating the backdrops for Oz, including the Emerald City, which he later claimed was inspired by childhood memories of Edinburgh Castle. His job was a feat of organisation as well as visual flair. Gibson built his department from scratch and oversaw the construction of a special building that allowed several artists to work together on one backdrop, often at least 150ft wide and 60ft high, each one a gigantic trompe l’oeil. There was no room for artistic ego. At work, Gibson believed in ‘the sacrifice of personal creativity in the interest of a uniform creation; the blending of various and differing degrees of talent […] in the interest of the whole’.

Gibson’s department exemplified the efficiencies of the studio system, the ‘assembly-line’ business practices that allowed Hollywood to produce tremendous films at scale throughout its Golden Age. Such rules, however profitable, are made to be broken. One of Gibson’s greatest achievements was An American in Paris (Vincente Minnelli, 1951), the MGM musical starring Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron. Though audiences would end up loving it for its imaginative splendour, the film’s climactic 17-minute ballet was a risky $450,000 sequence, for which Gibson’s team created a series of 300ft by 40ft backdrops. These gave depth to the film’s dioramic recreations of paintings of Parisian streets and nightclubs by 19th- and early 20th-century French artists, with the actors often impersonating specific figures from works of art – Toulouse-Lautrec’s dancing clown Chocolat (1896), for example, or the subject of Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Girl Gathering Flowers (c. 1872). According to Kelly, when Raoul Dufy – whose paintings of the Place de la Concorde inspired some of Gibson’s set design – saw a preview of the ballet scene, he wept with joy and immediately asked to see it again.

A publicity still from An American in Paris (dir. Vincente Minnelli, 1951), with a painted backdrop inspired by the work of Vincent Van Gogh. Photo: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Despite providing Gibson with such grand outlets for his creativity, Hollywood was a six-day-a-week paycheque job for the artist, who continued his own practice throughout his movie career. ‘It put a big crimp in my artistic activities in the 30s,’ Gibson told the Los Angeles Times in the 1990s. ‘But I still managed to paint and get exhibited.’ Gibson was one of the California Regionalists, a school that also included the painters Ralph Hulett and Emil Kosa Jr.; together they captured the majestic landscape of the Golden State as well as the slowly encroaching urban infrastructure, with tiny figures for scale.

Gibson was not the only Hollywood scenic artist of the group. Hulett was the art director on some of Walt Disney’s most popular animated features, and started out painting watercolour backgrounds for films such Pinocchio (1940) and Bambi (1942). Kosa Jr. was the art director of 20th Century Fox’s visual effects department – he won an Oscar for his work on Cleopatra (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1963). It is not difficult to see where the two disciplines overlap. Several of their watercolours have a depth of field – the palpable swell of hills receding into the distance, the generous proportions of sky – similar to that needed in a studio backdrop.

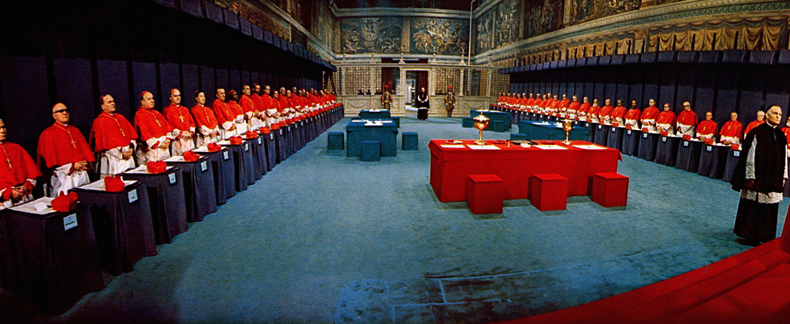

Gibson valued artists in his department who had studied weather and cloud formations. ‘Utter realism’ was something he strove for in both his landscape painting and his studio work. The enormous panoramic backdrops, 600ft wide, of the Scottish landscape that Gibson created for the fantasy musical Brigadoon (Vincente Minnelli, 1954) were so convincing that confused local birds flew into the soundstage, certain they were making for the hills. For the climax of the Hitchcock thriller North by Northwest (1959), Gibson recreated the vastness of Mount Rushmore on a studio backcloth. Michael Anderson’s Cold War epic The Shoes of the Fisherman (1968) was set in the Vatican, but Anderson did not have permission to film there – so in just three months Gibson and his team in Hollywood produced full-scale replicas of the Sistine Chapel frescos, which were transported at great expense to the Cinecittà studio in Rome where the film was being shot. Reportedly, Catholic clergy attending the film’s premiere were completely taken in, declaring themselves shocked that the film-makers had been granted access to the Chapel.

A still from The Shoes of the Fisherman (dir. Michael Anderson, 1968), set in the Sistine Chapel. Photo: Film Publicity Archive/United Archives via Getty Images

When Gibson died in 2001, at the age of 96, few people realised the scope of this artist’s contribution to Hollywood history. But it is no exaggeration to say that his beautiful illusions were loved by millions. Gibson’s tricks of the eye seemed, for the duration of a movie, even more tangible than the world outside the cinema. ‘Art and painting is life itself,’ he once said. ‘I can’t imagine life without painting.’