From the January 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

One of the first dishes cooked on television was an omelette. On the evening of 21 January 1937, for the first episode of Cook’s Night Out, the restaurateur and food writer Marcel Boulestin went live on the BBC for 15 minutes with a supporting cast of eggs and butter. Early broadcasts were not recorded, but Boulestin’s style is easily inferred from his 78rpm recording of the same cooking process: precise, punctilious and deadpan. ‘The omelette which is like scrambled eggs wrapped up in a pancake is not a good omelette,’ he says.

That pitfalls lie in wait for anyone boiling, poaching or scrambling eggs, or indeed making an omelette, has long been a touchstone of cookery writing. In 1942 the American writer M.F.K. Fisher instructed her readers ‘How Not to Boil an Egg’. Forty years later came Delia Smith’s Complete Cookery Course, with its author at once beckoning and admonishing the home cook with the egg that she is bran- dishing on the cover. Elizabeth David sent a friend instructions for scrambled eggs in the guise of a free-verse poem. Eggs are rarely as simple as they seem.

‘In cooking – as in almost everything else – it all starts with an egg,’ writes the chef Ruth Reichl in the foreword to The Gourmand’s Egg. A Collection of Stories & Recipes (Taschen), the first in a series of single-ingredient volumes devised by the editors of the eponymous food magazine. This is neither a straightforward cookery book, although about half of its pages are given over to recipes, nor a social and eco- nomic history in the manner of recent books about, say, herring, mustard or yoghurt (all in the Edible Series from Reaktion Books). Instead, through its abundance of illustrations, The Gourmand’s Egg celebrates the egg as form, image, symbol – and above all as an inexhaustible cultural reference point.

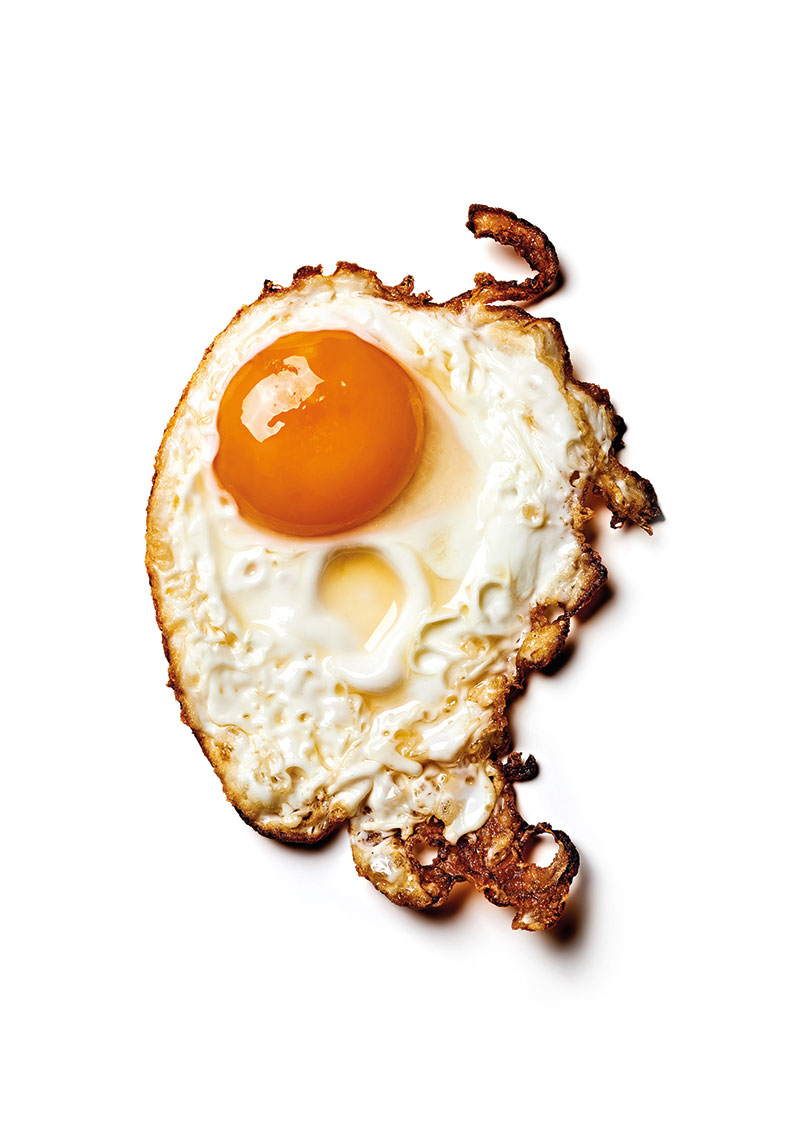

The Gourmand is one of a number of independent magazines, among them Gather Journal and Luncheon, which have over the past decade or so brought the high production values of fashion magazines to bear on food culture. More than its peers, perhaps, this title goes in for stylised photography that playfully reimagines ingredients as installation art, promoting kitchen staples to cover stars. The blown-up fried egg that graces the cover of the book makes for a grotesque but compelling image: it looks like an aerial photograph of some island that Gulliver might one day wash up on.

Fried egg, photographed by Bobby Doherty, and featured in The Gourmand’s Egg. A Collection of Stories & Recipes. Courtesy Taschen; photo: Bobby Doherty

The Gourmand’s editors-in-chief, David Lane and Marina Tweed, have clearly relished their egg hunt through art history. They give us full-page illustrations of eggs by Andy Warhol, Agnes Martin, Urs Fischer and others. An introduction by Jennifer Higgie dashes from antiquity to contemporary art, taking in eggs as symbols of purity, fertility and mortality or, for painters from Velázquez to Cedric Morris, as prompts for adventures in realism and representation. Higgie reminds us that for artists, through the techniques of tempera painting and albumen print photography, eggs have served not only as message but as medium. That versatility is no doubt part of their fascination: a quiche shares a common ingredient with The Birth of Venus.

In the series of short, unsigned essays that follows, the book turns its attention to everything from Fabergé to ‘Feminist eggs’, and from ‘Basquiat’s eyes and eggs’ to the provenance of eggs Benedict. The prose is insistently breezy and often list-like – the perfect conditions in which to hatch dan- gling modifiers, it turns out – but these essays are nevertheless rich with curiosities and diversions. We learn that egg-cup collectors are known as pocillovists; that the Beastie Boys ‘had a reputation for egg pranks’; that Alfred Hitchcock was scared of eggs. There is an entire section on the egg-cup finials that crown Terry Farrell’s Breakfast Television Centre building in Camden.

Contemporary photography punctuates the book. Most striking are the images by Bobby Doherty (who shot the cover), often showing giant, broken eggs, or the textures of shell and unctuous, oozing yolk in unnervingly sharp definition. The egg has a pristine form that invariably threatens chaos – which makes it perfect for tossing at politicians, perhaps, but always brings a touch of risk as the cook cracks one into the frying pan.

Gentler, but in their way stranger, are the photographs by Matthieu Lavanchy that illustrate the recipes. These show dishes from oblique angles, on tabletops set to evoke specific places: a scotch egg on the formica tabletop of a pub; a stack of pancakes accompanied by motel room keys in an American diner; a bowl of zabaglione in a trattoria, with a lipstick-smeared napkin alongside it. With their nostalgic palette, long shadows and sharp crops, these images thrust their egg dishes into narratives we can only guess at. The Gourmand’s Egg is full of terrible egg puns (‘Eggtymology’, ‘Eggcessories’ and so on) but these photographs make a more rewarding one: they are a quiet homage to William Eggleston.

From the January 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.