From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The fact that the Imperial War Museum has one of the largest collections of modern British art in the country will come as a surprise to those many people who think of it principally as a place to take children to look at tanks, guns, aeroplanes and trenches. Although in the past the museum has mounted exhibitions dedicated to such artists as Wyndham Lewis, Eric Ravilious and Henry Moore, and a few paintings feature in other displays devoted to individual conflicts, most of the collection remains hidden away. A programme of digitisation has made much of this material available online, but the new Blavatnik Galleries, which open this month, provide a long overdue space in the museum for a permanent show of artworks.

The IWM’s collection originated with the war art schemes initiated in 1916. The War Propaganda Bureau, established in 1914, was already making use of photographs and film taken at the front, but it had noticed that independent exhibitions of paintings by serving soldiers such as Eric Kennington, Paul and John Nash and C.R.W. Nevinson had attracted large crowds. This prompted the government to send Muirhead Bone to the Western Front as the first official war artist. Bone was merely tasked with providing illustrations for the magazine The War Pictorial, and it was not until the following year that artists were sent to the front in order to produce actual paintings. In 1918 the scheme became the responsibility of the British War Memorials Committee, formed under the auspices of the Ministry of Information with the intention of commissioning work that, rather than acting as propaganda, would create a permanent record of the war. The original intention was that the resulting artworks would be displayed in a large purpose-built Hall of Remembrance, and painters were instructed to conceive works on a grand scale in imitation of Uccello’s Battle of San Romano and other large Renaissance works. This resulted in such huge canvases as John Singer Sargent’s Gassed (1919) and Paul Nash’s The Menin Road of the same year, but in the event plans for the Hall of Remembrance were abandoned in favour of what would become the Imperial War Museum, first located in the Crystal Palace and opened to the public in 1920.

Art was, therefore, an essential part of the museum from its very founding, and in November 1939, as Britain once again found itself at war with Germany, the director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, was employed by the Ministry of Information to set up a new war artists’ scheme. Clark privately declared that his job was ‘simply to keep artists at work on any pretext, and, as far as possible, to prevent them from being killed’, but the real aim of the War Artists Advisory Committee was, like its predecessors, to assemble a pictorial record of life in all theatres of war and on the Home Front. Clark’s reputation for championing modern art raised concerns in the press that his taste was ‘so unequivocally advanced that it seems doubtful whether any painter whose technique and vision combine to interest, please or inspire ordinary people will be chosen’. In fact Clark recognised that ‘pure painters who are interested solely in putting down their feelings about shapes and colours, and not in facts, drama, and human emotions generally’ might not be suitable for the task and, although he gave work to Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland, the majority of the artists commissioned were more conventional. The first four artists to receive salaries rather than individual commissions were Barnett Freedman, Edward Ardizzone and Edward Bawden, all principally known as illustrators, and Reginald Eves, a well-known society portraitist. While the first three produced some extremely vivid records of life on several battlefronts, Eves spent his time in Arras painting wholly unremarkable likenesses of army leaders. Alongside the outstanding examples of 20th-century art in the IWM’s collection are hundreds of similarly uninspired paintings of generals, battleships and aircraft. For every work by Ravilious there are twice as many by John Hamilton, the kind of artist whose pictures of ships remind one of the most boring kind of 1940s jigsaw puzzle. In commissioning war art there has often been this tension between creating a properly representative visual record of conflict and encouraging work of lasting artistic merit.

Over the Top. 1st Artists’ Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917 (1918), John Nash. Imperial War Museum, London. © IWM Art.IWM ART 1656

The Blavatnik Galleries have to perform a similar balancing act and deciding which of the museum’s 16,000 or so paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, films and other artworks should be shown must have been an unimaginably difficult process. The four galleries occupy around 1,000 sq m on the third floor of the museum, in a space previously occupied by the old Holocaust Galleries. (The new Holocaust Galleries, which opened in 2021, are on the second floor.) The selection of artworks in the Blavatnik Galleries is admirably wide-ranging, both in subject and aesthetic response, without too much obvious box-ticking. A few of the most famous and popular paintings in the collection are here, including Gassed (which has recently undergone a lengthy conservation process), John Nash’s Over the Top (1918) and Laura Knight’s Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-ring (1943), but these take their place among many much less familiar works and a generous sample of recent and contemporary depictions of, or reactions to, warfare. The arrangement is thematic rather than chronological, which not only suggests the grim continuity of warfare during the last hundred years or so, but gives rise to some stimulating juxtapositions. An introduction and overview is supplied by the first gallery, which includes examples of work from all periods and in all mediums, from Walter Sickert’s Tipperary (1914) – in which a soldier leans out of a window beside a mirror that reflects a woman at the piano playing the famous marching song – to a poster issued by the Stop the War Coalition during the Iraq War in 2004 demanding ‘End the Torture. Bring the Troops Home Now’. These two items neatly encapsulate very different public attitudes to warfare involving British troops over a century of change, while at the same time illustrating how the IWM’s current remit to collect artworks has changed significantly from that of war artists’ schemes in the past.

Not that earlier, more traditional war art avoided controversy: a gallery devoted to the ‘Power of the Image’ juxtaposes two First World War paintings by C.R.W. Nevinson and William Orpen. As with film and photography, in the interests of national morale restrictions were placed on what artists could depict, and one subject strictly off limits was dead Allied troops. Orpen’s Dead Germans in a Trench (1918) was deemed completely acceptable, but that same year Nevinson was forbidden by the War Office to exhibit Paths of Glory (1917), in which dead British soldiers were shown face down in the mud. The painting’s title was of course provocative, and Nevinson responded to the ban by exhibiting the picture with a strip of brown paper bearing the word ‘CENSORED’ pasted across it. Other artworks in the ‘Power of the Image’ gallery include a selection of posters from other conflicts, as well as several paintings of the Nazi concentration camps, all by women who had either visited them when they were liberated or, in the case of Edith Birkin, had survived incarceration in them. Given that no paintings are included in the museum’s Holocaust Galleries, their inclusion here, alongside films and photographs, is particularly welcome.

Roll Call – Belsen, 1944 (1990), Edith Birkin. Imperial War Museum, London. © IWM Art.IWM ART 17440

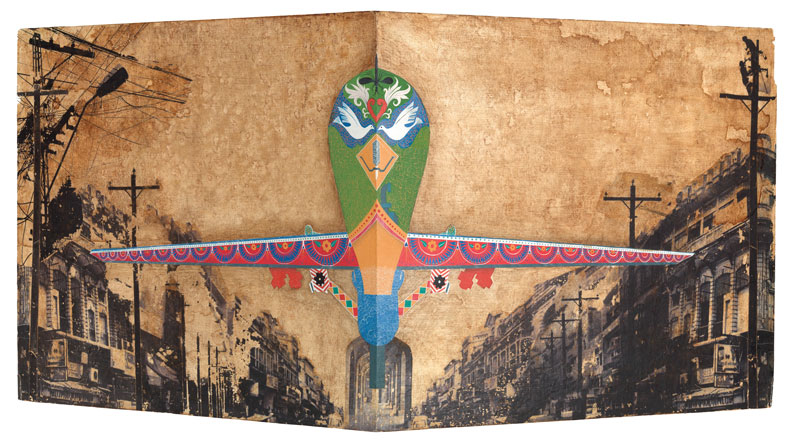

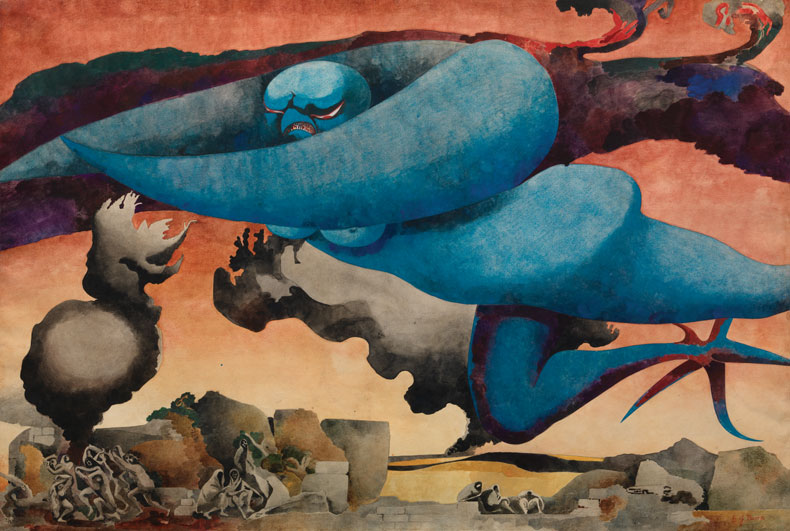

The gallery devoted to ‘Perspectives and Frontiers’ shows many of the different ways in which artists have responded to the environment of war, both as participants and observers. On the ground, newly mechanised warfare not only brought death and destruction from afar, but changed landscapes out of all recognition, while aeroplanes provided a new viewpoint from which to depict and map the world. The aerial bombardment of civilians during the Second World War produced some unusual Surrealist artworks, notably Julian Trevelyan’s Premonitions of the Blitz (1940), in which gun barrels protrude from the eye-sockets of a luridly coloured human face, and Edward Burra’s extraordinary Blue Baby, Blitz Over Britain (1941), where the monstrous and pneumatic figure of the title looms over smoking ruins and fleeing civilians. Here too are works that expand our notion of what war art might mean. Diana Matar’s Evidence XIV (2012) records in stark black-and-white photographs sites of political violence in Libya under the Gaddafi regime, during which her father-in-law disappeared and is presumed to have been murdered. In Mahwish Chishty’s three-dimensional By the Moonlight (2013) the silhouette of a Reaper drone painted with the kind of folk-art decorations one sees on trucks in Pakistan and India spreads its wings over the image of a Lahore streetscape.

By the Moonlight (2013), Mahwish Chishty. Imperial War Museum. © IWM Art.IWM ART LD 2740

The ‘Mind and Body’ gallery deals with the physical and mental impact of war. Alfred Thomson’s A Saline Bath, RAF Hospital (1943) emphasises the sudden vulnerability of wounded servicemen by depicting a naked airman being treated for burns by a fully clothed nurse. This might be compared with David Cotterell’s Gateway II (2009), a triptych of large-scale photographs of seriously injured men, surrounded by medical equipment and the hard industrial surfaces of aircraft as they are flown out of Camp Bastion in Afghanistan. Comparisons might also be made with a large painting of a forge in the national projectile factory on Hackney Marshes by Anna Airy, one of the very few women artists in the scheme during the First World War. The luminous red of the shell casings brilliantly conveys the oppressive heat of the forge and the potential dangers to the figures working there – not least Airy herself, who reported that the floor became so hot that ‘it burnt a pair of shoes right off my feet.’

A Saline Bath, RAF Hospital (1943), Alfred Reginald Thomson. Imperial War Museum, London. © IWM Art.IWM ART LD 3629

Showing alongside this curiously beautiful painting is Work Party, a cheery film about women working in an armaments factory made by Len Lye for the Ministry of Information in 1942. While the script leaves something to be desired – ‘Eight months ago these women knew nothing more mechanical than a kitchen stove; now they know the recipe for making guns’ – Lye manages to get in some shots of whirring mechanisms that suggest the lifelong interest in motion he explored in his more familiar experimental films and kinetic sculptures. Short films and extracts from longer ones are run on screens throughout the galleries, but there are also two cinema spaces in which programmed films will be shown. Among these are The Battle of Arras (1917), for which a new score has been specially commissioned, and the absurd Advice to Householders (1964), in which civilians are shown how to protect themselves against ‘the hazards of a nuclear attack’ by, for example, pushing heavy cupboards against their windows and filling them with earth or books.

An often overlooked aspect of the two World Wars is the huge number of Empire and colonial troops, who are well but not insistently represented here. It seems odd that none of Edward Bawden’s beautiful watercolours of Iraqi forces from the early 1940s are on show, nor anything from the IWM’s large collection of paintings Anthony Gross made in the Middle East at the same time. It is, however, good to see Leslie Cole’s energetic and beautifully composed painting of Basuto mail sorters in Malta (1943), in which the khaki-clad figures are almost overwhelmed by stacks of grey mailbags and an apparently rising tide of parcels. Nearby Cecil Beaton’s photographs of ‘native’ troops in India, Burma and China during the Second World War, which are among his finest works, are exhibited alongside Tim Hetherington’s haunting photographs of the victims of Sierra Leone’s long-running civil war (1991–2002). There was an attempt during the Second World War to commission works by artists from Africa, Jamaica and what was then Ceylon that expressed their own aesthetic rather than imitating European art. While a painting of the King’s Africa Rifles in action in the Western Desert by an artist named as Katongole (no further information is given) looks as modernist as anything by the more advanced of the British war artists, what strikes one most about John Wood’s ARP in Jamaica (c. 1940s) is the racial mix of the nurses surrounding the supine body of a Black man.

Portrait from the series Cecil Beaton in India, Burma and China, December 1943–August 1944 (c. 1943–44), Cecil Beaton. Imperial War Museum, London. © IWM IB 281

Since the Second World War, the nature of conflict has changed, as the large-scale battles familiar from the world wars have given way to smaller but equally murderous skirmishes, guerrilla actions, street fighting, ‘ethnic cleansing’ and terrorist attacks, all of which the IWM has a mission to represent. While some artists still go to front lines, others create installations, soundscapes and more conceptual forms of art from a distance. Steve McQueen was sent to Basra in 2006, but found conditions there impossible for making a film. Instead, back in Britain, he created Queen and Country (2006), a large cabinet containing sliding panels on which are displayed sheets of imitation postage stamps bearing portrait photographs of 160 British military personnel killed in the Iraq War. Effective as this piece is, it is perhaps harder now for artists to create work that adds anything to the often shocking images of contemporary warfare that are part of everyday news-feeds. Albert Adams’ drawings of the notorious abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, for example, are a good deal less powerful than the original photographs taken by American troops. At present there are no official war artists, though the museum says that there will be in the future. It continues to add to the collection through commission, purchase and donation, keeping a close eye on the contemporary art scene for any work that engages with conflict. As well as purchasing new work, such as Diana Matar’s, there is also the need to fill gaps in the collection: support from The Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund allowed the museum to buy Burra’s Blue Baby in 1993, for example.

Blue Baby, Blitz over Britain (1941), Edward Burra. Imperial War Museum, London. © IWM Art.IWM ART 16500

Artists have for centuries been intermediaries between the general public and those who fight wars on its behalf. If in both 1916 and 1939 the purpose of ‘war art’ seemed clear, this was largely because the lines of conflict were themselves clearly defined, and artists in the various schemes were deemed to be contributing to a war effort in which most of their fellow citizens firmly believed; the job of the war artist was to make a record of conflict rather than ask questions about how or why it was conducted. But this is no longer the case: war now knows no boundaries, with conflicts often involving foreign forces or fighters whose stated mission is ‘world order’ rather than the defence of their own territory, and this kind of military involvement can no longer rely on automatic public support. Protest and dissent have eroded once widely held notions of ‘patriotism’, while weapons such as the drone depicted by Mahwish Chishty have added a new dimension to discussions about the morality of warfare. These circumstances clearly affect the brief of the war artist, whether officially commissioned or simply drawn to warfare and its consequences as a subject, and the IWM sees the need to ‘reflect the wider cultural and social contexts’ in which war art is created. It is easier to raise questions about the ever-evolving meaning and purpose of art that takes conflict as its subject than to answer them; but in addition to putting on show some superb and little-seen works, the Blavatnik Galleries will provide a stimulating forum for the continuing debate.

The new art, film and photography galleries at the Imperial War Museum, London, open on 10 November.

From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.