The American artist Larry Bell is best known for his glass sculptures that range in scale from the small to the monumental, employing colour, light and shadow to play with our sense of perception. Since 1969, he has used a machine known as the ‘The Tank,’ which allows him to coat the glass in specific ways, altering how absorbent, transmissive, or reflective it appears. ‘Although we tend to think of glass as a window, it is a solid-liquid that has at once three distinctive qualities: it reflects light, it absorbs light, and it transmits light all at the same time,’ he has said of his primary material. Over the course of his career, he has also created paintings, works on paper and furniture designs. A solo exhibition of his new sculptural works is at Hauser & Wirth, London, until 30 July.

You have two studios, one in Los Angeles and one in Taos, New Mexico. Why those places in particular?

Well, part of it is greed. The other part is that I spent half of my early life in Los Angeles and I met my mate and had children in Taos. I should say, however, that it’s not really Los Angeles, it’s Venice Beach, which is quite different from the rest of the city. I like the air there. When I first lived in Venice [Beach] it was inexpensive and kind of dangerous: there were a lot of gangs. But it has changed a lot, since then. It has got a lot more expensive.

The reason I went to New Mexico in the first place was to see a friend of mine, a great artist called Ken Price, who was a sculptor and a great source of inspiration to me. He had moved there and I missed him greatly. When I went to see him, I fell in love with the place and by chance, acquired an old house that Ken had bought but decided not to keep. I took over the renovation, as a sort of favour to him and the person he was buying the house from. When I decided to stay, I locked the doors to my Venice Beach studio and kept it that way until the landlord said he didn’t want to have tenants who weren’t on the premises so I was obliged to leave. I hadn’t been working at that point and I didn’t really have any income except sales of work. What I did have, however, was the house I owned in Venice Beach so I sold that and it paid for the acquisition of a studio in Taos – a former commercial laundry. A huge space. All of the relics of the laundry business were still there, all the old washing machines, even though the building had been vacated for years. The ceiling was falling in. I bought it for nothing, as a joint purchase, with a friend of mine, with the intention of making both of our studios there and that’s what we did. We’re still partners. He is a photographer and uses half of the property, I use the other half.

No Entry (2021), Larry Bell. Photo: Alex Delfanne

How do you split your time between the studios?

I used to drive between the studios every three weeks. It’s roughly a thousand miles, a 14 hour drive, but I loved it. I don’t like driving in Los Angeles because there’s so much traffic and I worry I’m not such a good driver anymore, so I tend to get to Venice Beach and stay there, but the drive from Los Angeles to New Mexico is beautiful and nourishing: the vastness of the mountains, the desert.

Why every three weeks?

I don’t know. It just happened to work out that way. I began a new series of works on paper that became very addictive, but I couldn’t do the entire process in one place. I had to prepare the materials that I was going to work with in Taos and then drive to Venice [Beach] where I assembled and finished them. That was my routine. It was a very productive time and the pieces were wonderfully interesting: I found imagery coming out of all parts of my brain that were representative of my very personal passions. For example, I collect guitars. The works weren’t pictures of guitars, but they had the shapes of guitars in them, which isn’t something I planned, it just developed. But then, Covid happened and that was the end of that.

Do you think the drive itself influenced the work you were making?

I don’t think so. The drive was a cleansing period for me. When I got in my car in Venice Beach to drive home to Taos, Los Angeles slowly drained out of me. And when I got back, I would be exhausted from both the drive and the fact that the air was thinner (Taos is about 7,000 feet above sea level). Driving the other way was a completely opposite experience. I always felt great when I got to Venice Beach. I might be tired and sleep very well, but I woke up feeling terrific, whereas when I arrived in Taos I’d go to bed exhausted and wake up still tired. It took a few days to acclimatise to the altitude.

Deconstructed Cube SS (2021), Larry Bell. Photo: Jeff McLane

Is there anything that frustrates you about your studios?

No. Nothing has ever frustrated me about my studios. Every studio I’ve ever had has been successful in terms of what I’ve used it for.

You own a very unique piece of equipment: a 14-ton vacuum chamber known as The Tank, which you had specially made to produce your cubic works. What’s the story behind that?

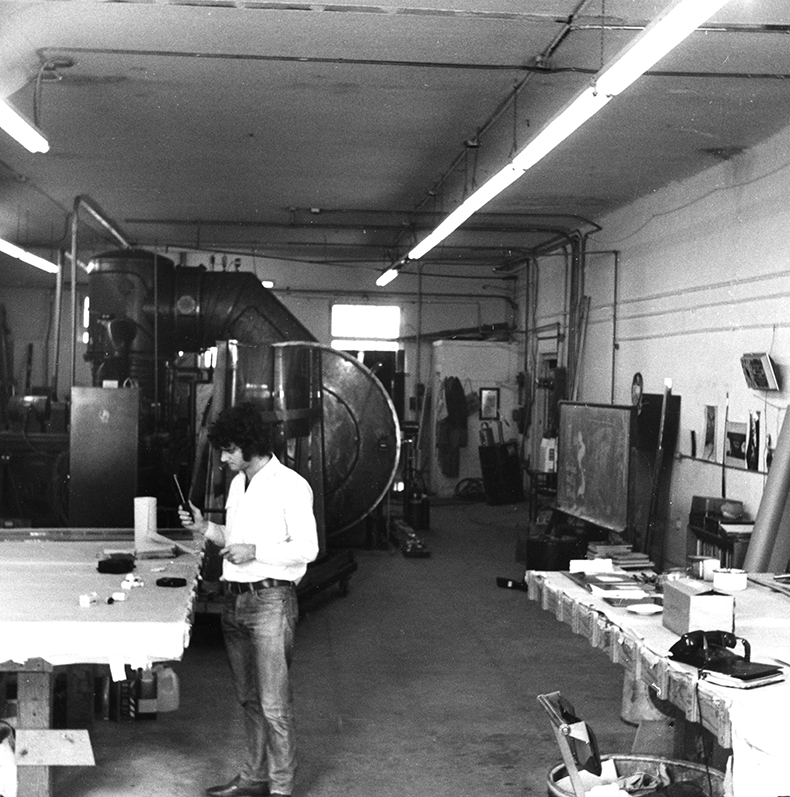

The Tank has been my friend for a long time. I ordered it to be built in 1968 and it arrived in 1969. We’ve used it ever since. It was originally delivered to Venice Beach, but when I got evicted from my studio I had to move everything to Taos and it just sat on the floor while we assembled the building around it.

Bell in his Venice Beach studio with The Tank in 1969 © Larry Bell. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

You mentioned you were inspired by your friend Ken Price’s work. Do you pin up work by any other artists?

No, I don’t. Ken was a ceramicist and he made very small, beautiful things. He also made coffee cups, some of which had animal figures on them, snails and things like that. I still have some of his pieces around in the studio. I drink my coffee out of one of his cups. Interestingly, even though they are vessels that you physically use, the way they sit on the table is quite unusual. The little creatures grab the platform. I’d say that his influence on how I made my sculptures presentable was quite profound, purely in the way the piece is set.

What’s the most well-thumbed book in your studio?

I have a big library. I get tonnes of books sent to me. I think the last art book I actually purchased is Codex Seraphinianus, which is by the Italian architect Luigi Serafini who drafted an encyclopaedia of the next species. I don’t read too much fiction anymore, but I used to collect the writings of HG Wells.

Do you follow a particular routine to prepare yourself to work?

It has changed as I’ve grown older. In the beginning, I did just about everything myself and then in the late sixties, I started working with an assistant who I met in New York. I’d gone to New York for a show, which was very successful and I decided to stay for a while because I was charmed by the place and the artists that I met. I was fortunate to become very good friends with a lot of people whose work I admired, but while I was there, there was the blizzard of 1966 and the blackout across the city which made me realise I am definitely not a New Yorker. But New York is where I met my first assistant: a French guy named Guy de Cointet, who was quite a good artist in his own right. He spoke no English and I spoke no French.

The Blue Gate (2021), Larry Bell. Photo: Alex Delfanne

How did you communicate?

[Laughs] I don’t know, but we did. We got along very well and when I moved back to Los Angeles, he came back with me. He passed away about fifteen years ago, but he was an extraordinary person. He influenced a lot of artists. He wrote plays and made these very strange drawings. There are a couple of books on his work available. In fact, some of his work just sold at auction in Los Angeles. One little piece, a wall thing with letters and stuff on it, sold for $84,000. I was very impressed. He would have been impressed too.

How many assistants do you have now?

I have seven – and I think of them as my family. The people I have working with me are really fantastic. I don’t think I deserve to have people of this calibre working with me, but I try to pay them well, to do what I can for them.

Who’s the most interesting visitor you’ve ever had to the studio?

Marcel Duchamp came to my studio once. A surprise visit. I didn’t know who he was. Three people showed up knocking on the door and I didn’t answer because at that time the only people who came to the front door were building inspectors (you weren’t allowed to live in a commercial space). So, everyone I knew came to the back door. Anyway, they were out there gently rapping on the door, continuously for about twenty minutes so eventually I answered it. They were wearing suits so I was convinced they were inspectors but the first thing one of them said was, ‘Walter Hopps sent us.’ Walter Hopps was my dealer in Los Angeles so I knew I didn’t have to worry. I was born with a very severe hearing loss and this was before I got hearing aids so I didn’t understand their names. As it turned out, one of them was a Surrealist painter called William Copley, one was the British artist Richard Hamilton and one was Marcel Duchamp.

‘Larry Bell: New Works’ is at Hauser & Wirth, 23 Savile Row, London, until 30 July 2022.