Making abstract paintings about political or philosophical questions is one of the trickiest tasks an artist can set themselves. Paint can do a lot, but marks on canvas can only be so specific when trying to investigate something like the nature of being. Yet a retrospective at MoMA shows that Jack Whitten spent his whole life doing so, torturing and transforming paint to satisfy his boundless curiosity.

The earliest paintings in the show, from the mid to late 1960s, are influenced by de Kooning (a friend) and comprise a mishmash of darting strokes full of energy and enthusiasm – even if they lack an overall coherence. In the King’s Garden series, for example, streaks of almost every primary and secondary colour compete for control of the canvas, resulting in messy paintings a touch overwhelmed by their own excitement. Whitten, however, seems to have come into his own as a painter once he gave up any attachment to his own dexterity.

NY Battleground (1967), Jack Whitten. Museum of Modern Art, New York; © Estate of Jack Whitten

In 1970, he created a tool called ‘the developer’: two pieces of wood joined to form a ‘T’ taller than he was, which he wielded like a beach umbrella in a storm. He laid multiple layers of acrylic paint on canvas, and while each was at a different stage of drying, he would rake this contraption across the surface, making a whole painting in one gesture. The colours would bleed and cut into each other as he was ripping the face off reality – tearing through the top layer of skin to unveil the gory, sinuous tissue underneath what the naked eye can see.

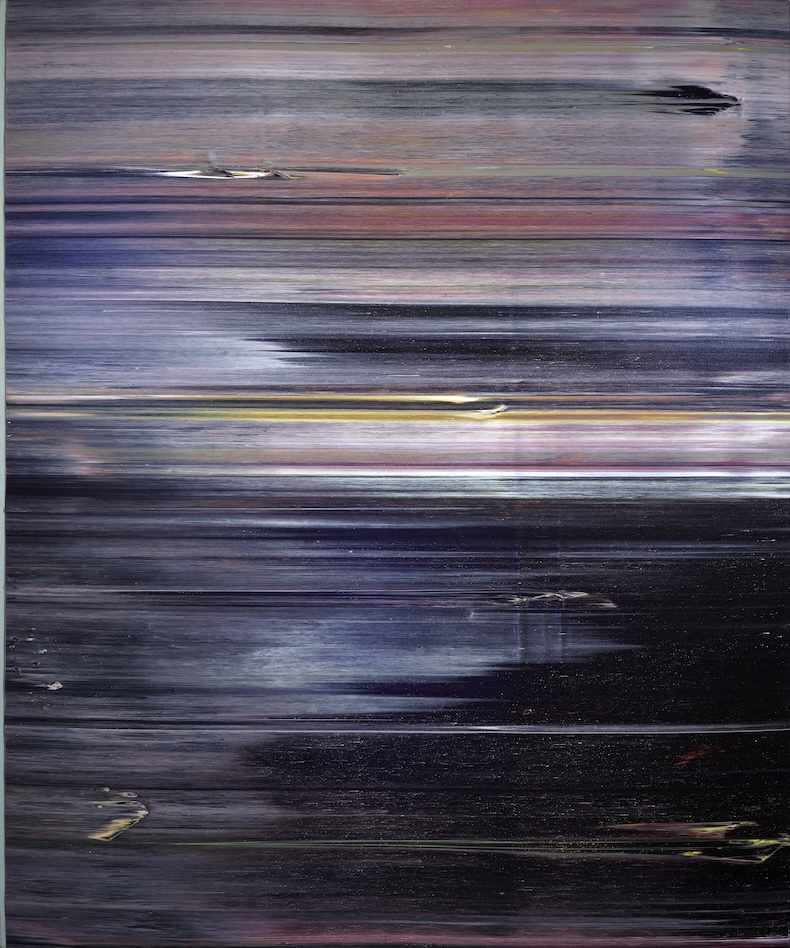

Whitten’s most successful paintings show few, if any, signs of human touch. Chance seems to be the operating factor here. He gives up control of the painting – either by letting the ‘developer’ do what it does or, in his more collage-like works, letting the materials (which included ash, molasses, copper, salt, hair, and more) speak for themselves. MoMA nudges them to talk, however, by playing jazz through overhead speakers in the galleries. Looking at Black Table Setting (Homage to Duke Ellington), I followed a yellow streak shoot and disappear across a background of purple and black while listening to a piano melody slowly merge with the bass and drums of Ellington’s ‘In a Sentimental Mood’.

Black Table Setting (Homage to Duke Ellington) (1974), Jack Whitten. Birmingham Museum of Art. © Estate of Jack Whitten

Whitten was inspired by quantum mechanics and Zen Buddhism, disciplines that challenge basic notions about how the world works by suggesting that we’re less in charge than we think. In the presence of Whitten’s paintings I wondered how paint pushed around randomly can be so full of verve. But perhaps Whitten does not give life to his materials so much as reveal a pulse that’s already there.

Not all of Whitten’s inspirations were so abstract. He grew up in the segregated South, and helped organise civil rights demonstrations as a student. He respected Martin Luther King’s philosophy of non-violence, but couldn’t commit to it. After less than a year of activism, he realised that he needed to leave the South, he said, because either ‘I would be killed or I would end up killing somebody.’ Whitten moved to New York to study at Cooper Union, through which he met other Black artists, such as Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence and Melvin Edwards. He started with gestural abstraction as a pure expression of feeling, but later moved towards a cooler geometric style with no loss of rawness. Much later, in the 1990s, he invented a tessellation technique that involved pouring deep pools of acrylic paint (and sometimes even his own blood) on to a surface, letting the viscous mixture dry and then snapping off hardened chips, which he would fix to the canvas like a mosaic. The resulting ashy, fractured surfaces – as in Totem 2000 IV: For Amadou Diallo, made in remembrance of a Guinean student killed by New York police in 1999 – suck the energy out of the room, as they are meant to.

Each work in the Black Monolith series, which began in the 1960s and continued alongside other projects until his death, pays tribute to a figure who made significant contributions to culture, sport or politics. Black Monolith X (The Birth of Muhammad Ali) comprises two misshapen black ovals, one larger than the other, surrounded by shining shards of different coloured paint. It all coalesces into a grey mess that looks like maggots crawling around the surface. All the Black Monoliths likewise feature distinct oblong shapes that take form against a chaotic background of fragments.

Black Monolith VII (Du Bois Legacy: For W.E. Burghardt) (2014), Jack Whitten. Courtesy Charlotte and Herbert S. Wagner; © Estate of Jack Whitten

Towards the end, Whitten turned his attention to digital technology. His puzzling, though mesmerising, painting Apps for Obama resembles an iPad home screen with app icons that look like bejewelled planets suspended in light-blue space. Obama may have presided over great advances in technology, but it’s hard to see his direct connection to the iPad. Either way, I take it as evidence that Whitten never stopped examining the world around him.

In 1972, Whitten wrote in his studio log, ‘I’ve done so much. I’ve tried everything […but] I still come back to surface. Please I am trying hard not to be confused. This shit is complicated! To be as clear as possible without getting confused. I JUST WANT A SLAB of PAINT.’ Many of the log entries alternate between plaintive and assertive exclamations in all caps. His slabs of paint – whether cracked, pushed, dragged or reassembled – gave voice to his troubling thoughts. The resulting paintings are monuments to ambiguity and unrest, animated by Whitten’s relentless resolve to question everything.

Mirsinaki Blue (1974), Jack Whitten. Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University; © Estate of Jack Whitten

‘Jack Whitten: The Messager’ is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 2 August.