Perhaps artist Jacqueline Humphries is coming back. She left her shovel, Sign (2019), by the door. Maybe she will return from her travels with more driftwood to hang next to Driftwood (2019) and Driftwood Brown (2019), more shells for Collection’s (2019) table. The objects in her show at the Dia Foundation’s Dan Flavin Art Institute on Long Island seem to have been included in this way, encountered on the shore and brought to shelter in the museum, a former fire station less than three miles from the beach. For now the works remain as Humphries left them: in a cellar-like ground floor gallery with the doors closed, letting in few outside disturbances, least of all light.

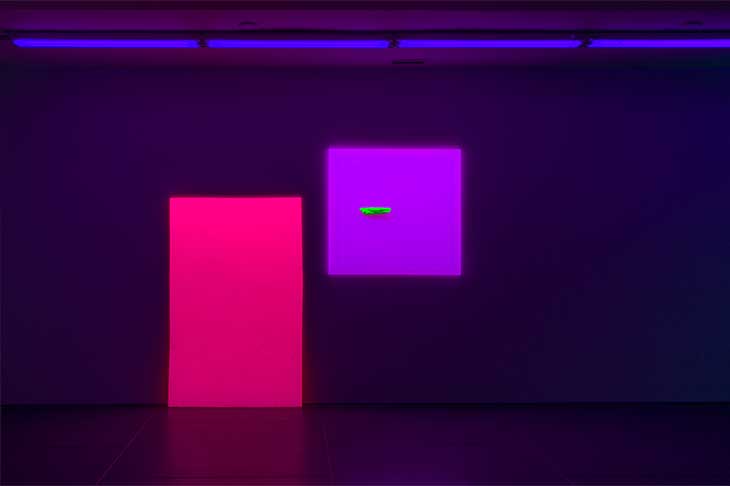

Installation view of ‘Jacqueline Humphries’ at the Dan Flavin Art Institute, Bridgehampton, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York; © Jacqueline Humphries

Speculation about the artist’s methods is understandable in a show in which reality itself is almost taboo. None of the objects were ‘found’ at all but, rather, they are cast or 3D-printed resin versions of driftwood, sea shells, and Humphries’ earlier paintings. Humphries leave clues about the fabrication process, magnifying the grain of the driftwood to make it uncanny. She exaggerates the artificiality through the fluorescent pigments she adds to all her objects; lit by overhead UV panels, the paint glows in a spectacular manner. Although the naked eye cannot perceive colour past violet, having only in the past few millennia caught up to blue, humans have made good use of what’s otherwise invisible to them, turning ultraviolet into a tool for exposure and detection. In art conservation, UV is used to detect the fake and the real: phosphors from newer paint glimmer under its focus while older paint does not. Humphries’ shining objects are not forgeries of another artwork but they confuse the eye in other ways: is the neon green driftwood that protrudes from Painting (2019) a hologram, 3D or 2D? Visitors ask the attendant if they can touch the work to check. The attendant apologises and says no, please don’t touch the art.

Installation view of ‘Jacqueline Humphries’ at the Dan Flavin Art Institute, Bridgehampton, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York; © Jacqueline Humphries

The works can’t be touched because they are as susceptible to dirt and oil as any art object. The forgery will also age. Humphries’ motif of driftwood is perhaps helpful, an example of how an object’s origins – real or fake – are not the same as its essence, and that the journey can create a new reality. What deceased wood driftwood did or did not degenerate from is less relevant than the time it may have spent marooned on a wave, beaching itself finally on the Long Island shore or in a Long Island gallery, where in either case it ended its travel in collapse – the driftwood in Collection is just a few inches off the ground – at the visitor’s feet. Another piece of driftwood, dried like a fish, is caught in the planks of the scaffold of Billboard (2019), the grimiest piece in the show, crusted and opaque. In advertising, a lot of things that claim to be honest are obfuscations – is art so different? Lest art become a false idol, free from owners or affiliations, Humphries etches the name of her sponsor into half of the works: DIA, DIA, DIA.

The exhibition requires open-mindedness. Yet these are strange times for the open mind. Information can be false and even our senses can betray us, corroborating the fake and smearing the real. Humphries understands this confusion. The exhibition’s failure to confirm 3D or 2D, real or fake is most tolerable in the pursuit of more questioning, as unraveling as that can be. If a visitor were to touch Painting they would draw evidence from a show meant entirely to invite speculation. It may or may not confirm the reality the visitor is looking for, but their fingerprint will have changed the work completely.

‘Jacqueline Humphries’ is at the Dan Flavin Art Institute, Bridgehampton, New York, until 17 May 2020.