From the May 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It’s a little after 10pm on a Saturday night and I’m standing in half a foot of water at the bottom of a medieval cistern in Coimbra in Portugal. I’m drinking a maple syrup mai tai and leaning against a makeshift tiki bar festooned with bamboo sticks and coloured lights. From a speaker on the side of the bar, Elvis is singing ‘Hawaiian Wedding Song’, his voice quavering around the high stone walls and vaulted ceiling, stretched by the echoes into phantom trails of vapour. There’s a hole in the roof like a ruined basketball net. A couple slowly dance, arm in arm, their rubber boots sploshing with each step. Reflections from the lights draw kaleidoscopic streaks in the water round my feet. Rarely has a work of art felt quite so much like stepping into another person’s dream.

The first time Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller showed their Blue Hawaii Bar it was in 2007 in Darmstadt. At the time, their exhibition at the German city’s Institut Mathildenhöhe was billed as the couple’s largest retrospective to date. But ‘The Factory of Shadows’, their present show at Coimbra’s monastery of Santa Clara-a-Nova, may be an even more ambitious undertaking. Featuring some of the oldest works in their catalogue, from the early ’90s, right up to more recent installations such as The Instrument of Troubled Dreams from 2018, and including several rarely seen works, the exhibition spreads across the vast 13,000 square footage of the late 17th-century former nunnery.

The 17th-century former monastery of Santa Clara-e-Nova, now home to the Coimbra biennial. Photo: ©Jorge das Nevas; courtesy Anozero – Bienal de Coimbra, 2025

It is a huge and at times bewildering space, in which multiple layers of history jostle for attention: decorative blue-and-white azulejo tilework rubbing up against starker remnants from the building’s military occupation in the 20th century. The army abandoned the place in 2006, leaving it more or less in ruins. But since 2017, it’s been the principal venue of the Bienal de Coimbra, and in the odd years the organisation behind the biennial arranges solo shows here, of which Cardiff and Miller’s is the third.

The first time I was really moved by a work by Miller and Cardiff was about eight years ago on an island called Teshima in the middle of Japan’s Seto Inland Sea, where the Benesse Corporation has spent the last couple of decades converting old fishermen’s cottages into permanent installations. I had seen Cardiff’s The Forty Part Motet (2001) prior to that, in the tanks at the Tate Modern, and liked it. I was somewhat familiar with the Thomas Tallis piece Spem in alium already and hearing the parts split into 40 different speakers, all in a circle, was lovely. But it was the Storm House the couple created on Teshima that hit me. Outside the sun shone, but inside the house, water dripped in buckets, lights flickered and rain poured down the windows to the sound of thunder and storm-force winds. It felt like I had stepped into another world, like a ghost drifting through someone else’s reality.

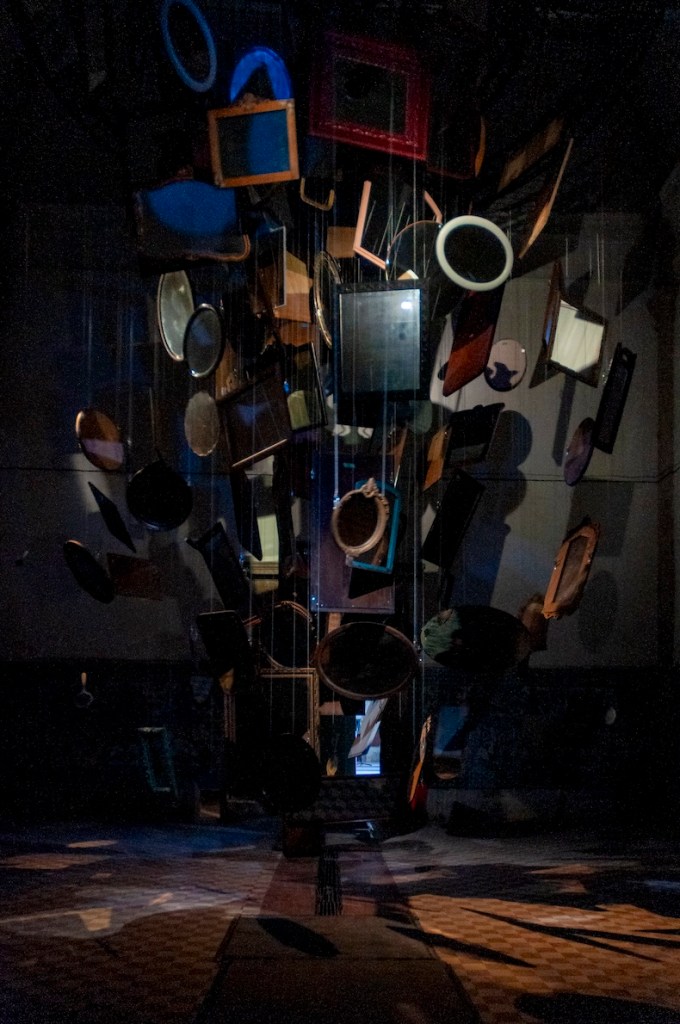

Installation view of The Infinity Machine by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller in ‘The Factory of Shadows’ at the former monastery of Santa Clara-a-Nova in Coimbra. Photo: courtesy Anozero – Bienal de Coimbra, 2025

Seeing The Forty Part Motet again in Coimbra, I was much more impressed. Something about the monastery’s ecclesiastical architecture suited the sound – not to mention the vibe – of the piece. There’s a moment in every Cardiff-Miller work where the deftness of the initial idea gives way to something deeper, more affecting. In The Forty Part Motet it’s the moment, previously missed among the crowds at the Tate, when after 14 minutes of singing the music stops and we hear all sorts of other little noises: the singers cough and clear their throat or take direction from the conductor, winding down from one run-through and preparing for another. Suddenly, you’re dragged right out of the ideal space of the music and shoved into another: immediately real, but somehow obscure, a little uncanny.

Wandering through ‘The Factory of Shadows’ is a haunting experience, full of spectral voices and disinterred histories. As soon as you come through the door, you’re confronted with Miller’s Curtain (1990–2024). It’s a simple conceit: just a ragged piece of black cloth suspended from a stand with a set of four spots directed at it, flashing out of sync. Somehow it’s enough to create the vivid impression of a fire through the flickering shadows cast on the wall. But every curtain hides a secret. In a striking confluence of work and site, set into the wall directly behind Miller’s floating veil is a forbidding metal contraption called the roda dos enjeitados (‘foundling wheel’), once used to shuttle abandoned infants to the nuns cloistered in the floors above.

In a darkened room upstairs, a work called To Touch (1993) invites tactile participation. When you do pass your hand across the heavy old carpenter’s table sitting at a jaunty angle across the room, sounds emerge, as if out of nowhere: a woman’s voice reciting the alphabet, birdsong, a ringing phone, knives sharpening with a satisfying shwink, fragments of stories. As with Curtain downstairs, there’s a certain sleight of hand here: the sounds are triggered not by touch but by a light sensor from above. But it’s good that the work encourages you to lay your hands on the table itself: it has its own histories, written in every scratch and streak of old paint, in the knots and rings of the wood.

Throughout the exhibition, it feels as if the building itself adds depth and richness to the work being shown. It is a feeling made more poignant by the threat currently hanging over the monastery to transform it into a five-star hotel ready to serve Coimbra’s burgeoning tourist industry – a project that would undoubtedly have to erase all character from the place. There are similar processes at work in town, where the city’s traditional communal student houses are being bought up by developers, whitewashed and leased back to the students who once collectively owned them, now at eye-watering rents. At its heart, so much of Cardiff and Miller’s work is about what it means to inhabit a place.

‘The Factory of Shadows’ is at the Santa Clara-a-Nova monastery, Coimbra, until 5 July.

From the May 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.