From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The objects are the stars at the Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. Glittering, glistening, perfectly lit. Glinting and gleaming, sparkling and shimmering. The museum loves its luminous collection and wants its visitors to love it, too.

Inevitably, for some of those visitors, the new setting is a loss. The Guggenheim Hall of Minerals and the Morgan Memorial Hall of Gems that displayed this collection from 1976 to 2017 did so under a radically different aesthetic. Tucked away in the recesses of the museum, the main room was dark, circular, carpeted, and stepped like an amphitheatre. A refuge from the intensities outside, the galleries formed a cul-de-sac, intimate and womb-like, though increasingly frayed as the decades passed.

The new halls, designed by Ralph Appelbaum Associates – who previously revamped the museum’s beloved dinosaur halls and the giant Hall of the Universe and planetarium wing that overlooks 81st Street – display the collection’s quality, range, and depth, and are another major step in the updating of the venerable institution and its exhibition spaces. The emerging museum not only looks but also feels contemporary: uncertain in its response to the legacies of provenance and display targeted by indigenous and decolonial activists; assertively democratic in its expansive vision of the 21st-century science museum as an engine of education and research; at ease with the accommodations demanded by the reliance of public goods on private money.

Like all great natural history museums, the AMNH draws on a double inheritance, the popular tradition of generalist inquiry and collection persisting alongside the modern disciplinary specialisations that long ago banished amateur enthusiasts from the formal sciences. In the new Gems and Minerals Halls, the collection is arranged to stimulate curiosity among visitors of all ages and levels of expertise and to reveal the fundamentals and advances in the forbiddingly technical work of professional geology. It’s a challenging task. (Consider, by contrast, the much more modest commitment of most metropolitan art institutions to conveying the rudiments of art history or aesthetic theory through their galleries.) And it’s why, on entering the new halls, we’re greeted by a towering Uruguayan amethyst geode right next to a label introducing the unifying theme of mineral evolution. This is the pairing that anchors the project: nature’s wonders as the gateway to an understanding of the physical and chemical processes that give them their astonishing properties and form.

There are, in fact, two enormous, twinkling 135-million-year-old amethyst geodes positioned back-to-back at the entrance to the galleries. And they are wonders, catalysts to the poetic as well as scientific imagination, doorways to the infinite vastness of the universe, depth-defying portals through which to drift through space and time. One entire side of the cavernous room is a Systematics Wall on which thousands of specimens, organised by chemistry, are laid out in sequence, all grounded by an introductory video, a large-scale animated periodic table, and brief object labels (‘Calcite. Harz Mountains, Lower Saxony, Germany.’ ‘Diopside. Orford, Quebec, Canada.’ ‘Fluoride. Minerva Mine, Cave-in-Rock, Illinois, USA. Gift of Fred Gardner.’). The regular, grid-like spacing of the specimens encourages comparisons while highlighting variation. The minerals float on discreet mounts; against the neutral background, they pop – a thrilling parade of colour, texture, structure, and dimensionality.

Throughout, the hall features spectacular and exemplary free-standing specimens, including a giant block of labradorite with unusually large crystals; the massively psychedelic, azurite and malachite Singing Stone from Bisbee, Arizona; the cranberry-coloured Tarugo elbaite tourmaline from Minas Gerais (‘one of the largest intact mineral crystals ever found’); and a show-stopping stibnite resembling an enormous metallic bird’s nest. Around these are large cases with independent displays on key geological forms and processes (igneous, metamorphic, hydrothermal, pegmatitic, weathering, fluorescence) and on geology specific to the New York region. These, too, include significant objects such as the deep-blue Newmont azurite from the Tsumeb mine in northern Namibia, considered by many collectors to be among the world’s finest mineral specimens, as well as the famous jewels and gems (the star sapphires!) which, ultimately, are likely to be the halls’ main attraction.

There are the stones that we pick up on the beach or in the woods or the park and there are the ones we might place on graves or present to a friend. Maybe we’re drawn to them by individual detail – something idiosyncratic, mimetic, or associative about the shape, surface, or colour; something telling about the way they hold or return the light; just something. Those stones might speak to place, to the moment of encounter, perhaps to a larger cosmic story of personal connection, perhaps of endurance or change. For many of us, such instinctive and impulsive objects become an archive of experience, perhaps of travel, of remembered – or forgotten – days. But the Museum draws a sharp geological line between those souvenirs and the specialist objects of its collection. These are minerals, distinct from rocks and stones, crystals, and fossils. They are, rather, the compositional foundation of rocks, stones, and fossils, each one ‘a naturally occurring solid with a regularly repeating crystal structure and defined chemical composition’. There’s no hint here of the controversies over what gets counted among the 5,700 minerals recognised by the International Mineralogical Association. (Should the scores of distinct biominerals created by living organisms be included, for example? And if not, why?) Still, the taxonomic wall this definition generates is so impressive that the simplification feels justified – even if it gives the impression of science as a domain of certainty rather than of exploration, experiment and speculation.

Across the Atlantic, in Paris, the Mineralogy and Geology Gallery at the Jardin des Plantes site of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle was also renovated in the last decade. But here, rather than a massive amethyst, visitors are greeted by glowing specimens from the collection of the Surrealist writer Roger Caillois (1913–78). Many of these are polished slices – of agate, chalcedony, jasper, onyx – and, as Caillois revealed in The Writing of Stones, his guide to the collection, each is an occasion for philosophical reflection. ‘The vision the eye records is always impoverished and uncertain,’ he wrote. ‘Imagination fills it out with the treasures of memory and knowledge.’ Caillois was the exponent of what he called ‘diagonal science’, a method of taxonomy based on associative, often morphological, connections between animals, plants, and objects, and he was especially drawn to the pictorial qualities of stones – the often uncanny resemblances between apparently unconnected phenomena – and the ways in which they stimulated his associative faculties, provoking his investigations of the sources of culture, the significance of symbolism, and the nature of dreams. Surveying his collection, Caillois stops at a striking black Brazilian onyx with angular white veining, now included on the middle shelf of the Paris display: ‘Suddenly you wonder whether this might not really be writing instead of images of a thousand other things.’

Within the Paris gallery, Caillois’s collection is followed by a geological presentation that is smaller but otherwise similar in quality and style to the one at the AMNH. It, too, wants the stones to serve as a gateway to science. But the tone of reflexive philosophical inquiry is already established and the definitions invite contemplation: ‘A mineral is a natural solid, usually organic, resulting from geological processes. It is defined by its chemical composition and orderly crystalline structure, that is to say by the repetitive and intermittent arrangement of its constituent atoms in three-dimensional space. As always, there are exceptions: native mercury is a liquid; opals do not have an orderly atomic structure…’

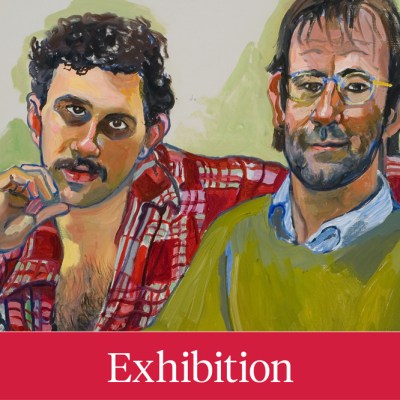

Geological specimens from the collection of Roger Caillois (1913–78). Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. Photo: Hugh Raffles

Caillois’s relationship with his collection was shaped by Chinese and Japanese traditions of stone appreciation. He came to believe that certain rocks and stones ‘reduce space, they condense time’, and that geological explanation only partly explains their meaning and power. Classical and contemporary East Asian collectors and scholars might draw on Confucianism to describe how a stone provides a model of an upright life, unyielding to the winds of political change, as well as on Daoism, that likewise proposes self-cultivation but in the pursuit of transcendence, of the dissolution of self through meditation and other techniques of spiritual discipline. The rocks, stones, and minerals in a Chinese or Japanese museum, classical garden, private collection, or auction house are likely to be valued for their form, texture, patina, colour, energy and, of course, resemblance – a range of graduated and overlapping criteria that can deepen the connection between a particular stone and its sympathetic and informed viewer.

If you happen to be in Manhattan, you can bridge these epistemological and aesthetic divides in an afternoon. The new halls of gems and minerals at the American Museum of Natural History include outstanding examples of some of Caillois’s favourite stones – ‘ruin marble’ from Tuscany, Mexican and Brazilian agates, jasper from the United States – objects from which we all might develop our geological knowledge and also conjure unexpected association and meaning. Across the park, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Astor Court is a meticulous recreation of a Ming garden courtyard from Suzhou, China, that includes several Taihu limestone rocks, tall and tapered with their characteristic perforations, creators and conduits of the energy that flows between biological and mineral life, simultaneously marking and eroding the distinction.

Among the specimens now on display at the AMNH is a large book of muscovite that I used to visit in the old Guggenheim display. To me, even in its newly bright surroundings, the dull-coloured object seems to brood and throb. This is because whenever I see musco- vite I think of the year my great-aunt spent as a forced labourer in the Nazi concentration camp at Theresienstadt, using a razor to cut blocks like this into impossibly thin slices for use in aircraft production. The heavy-looking object concentrates history with a dark power that resonates through the glass of the vitrine. I wonder how and from where the museum acquired it and how many other people react as I do when they see it. I wonder how many other objects here with different stories have comparable resonance for other visitors. This is without doubt a formidable geological specimen and it’s interesting to learn more about its pegmatitic origins and the qualities that made it so essential to the Luftwaffe. But it is, of course, also more than this. And that surplus, which manifests in many ways, is part of the power of the collection – the capacity of these objects to open themselves to disparate, not always overlapping, interpretation, to exceed explanation, and to compel and reward extended and repeated encounter.

From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.