From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Given that the artist is so interested in finding new languages – visual, verbal, experiential – there is something surprisingly provocative about finding Julie Mehretu unable to take part in our scheduled interview because she has lost her voice. It isn’t Covid or illness, it seems, that disrupts our plans, but exhaustion. She is in the midst of preparing for an exhibition at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, which, as anyone who has visited its huge galleries will know, is not a small proposition. Fittingly, when we do finally speak, she is in Frankfurt airport: Mehretu is an international artist in every sense.

Born in Addis Ababa in 1970, to an Ethiopian father and a Jewish-American mother, she moved with her family to East Lansing in Michigan in 1977. This was not the end of her travelling (Mehretu has also lived in Zimbabwe, Senegal and Europe), which she credits with having given her a different perspective on both her work and the world. ‘Having been raised elsewhere, having travelled a lot from a very young age […] I just have a very different engagement with these places,’ she says. At one stage during our conversation Mehretu pointedly remarks, ‘I’m talking about the multitude of histories of painting that are out there.’ Both her attitude and her work – paintings that combine layers of different kinds of image and fuse abstract marks with more literal pictures – give the sense of expansiveness and inclusivity.

A large retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 2019 confirmed that Mehretu is considered one of the foremost artists of her generation in America. The Whitney, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Walker have all also held major exhibitions of her work: this roll call suggests an artist who is, if not at the heart of the art establishment, then certainly well integrated within it. Mehretu wryly points out that all her big exhibitions in the United States have taken place in rooms designed by the same man: Renzo Piano. The Grassi, owned by fashion magnate François Pinault – who also happens to own Christie’s auction house – should be a different experience.

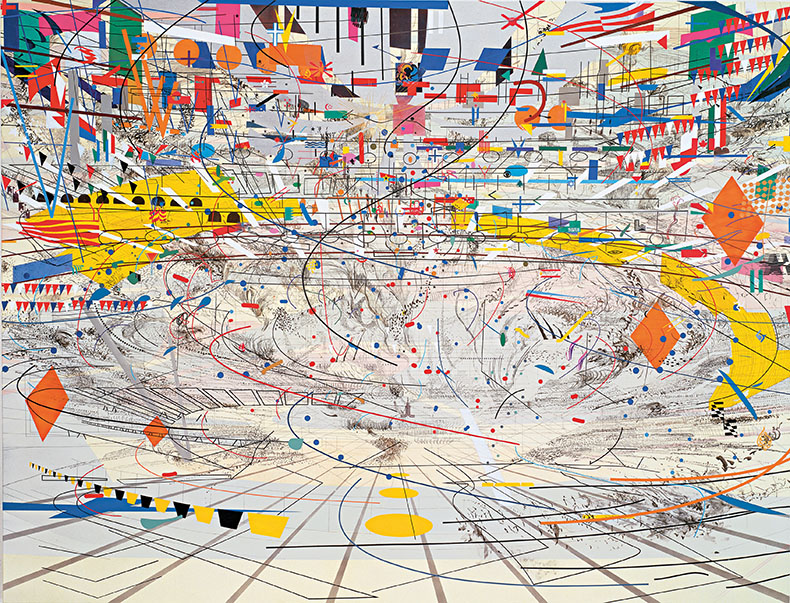

Transcending The New International (2003), Julie Mehretu. Photo: © Cameron Wittig; courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and White Cube; © Julie Mehretu

Mehretu’s art came to wider attention at the start of the millennium, a time when brash conceptual work (the inescapable Damien Hirsts) and bright paintings (the relentless Richard Princes) were in vogue. Mehretu’s detailed, muted works struck a different note. She wanted the viewer, she says, ‘to have different perspectives with the work’. This demanded a certain sort of commitment on her part. ‘The paintings had to get large, so that you could see them from up close [from where] they look like these intimate drawings and the painting fractures into all these intimate realities […] but when you pull away, you have a very different image of the painting as a whole, and it coalesces into something else.’

It was an almost gratuitously intellectual approach for the time – restructuring realities is a bold philosophical proposition that might appeal to an art lover yearning for seriousness. Mehretu’s credentials were further bolstered by the materials she deployed, using architectural plans as the background for abstractions over which she painted or drew. She painstakingly erased elements of the plans and merged them with other maps to create very specific social commentaries.

Transcending: The New International (2003) took Mehretu back to the city of her birth with a map of Addis Ababa as the ground. Over this, she placed maps of other African political and economic centres, along with architectural drawings of colonial buildings and modern, post-liberation landmarks. The marks on the canvas operate as a sort of palimpsest of experience from across the continent: a map of power and control. But playing across the surface are gestures drawn by Mehretu that stand for a freedom absent from the rigid plans and buildings of history.

Only a year later, Mehretu completed her Stadia triptych. The plan that underlies these works is not the detailed, distanced plan of a city but a drawing of a stadium. Curves and grids come together to imply the forced organisation of a structure that is usually seen as a centre of pleasure and sport, but which takes on a more shadowy meaning in other contexts. No building is more useful for bringing people together, whether that’s for laughter or a political rally. Hovering over the lines of the stadium in Mehretu’s paintings are blocks of colour that invite comparisons to other forms and other artists.

Stadia II (2004), Julie Mehretu. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. Photo: © Richard Stoner; courtesy White Cube; © Julie Mehretu

Mehretu describes the gestures that expand the background material beyond the merely archival as ‘neologisms’. They started ‘much smaller’ than they are now, ‘the marks of a little rapidograph pen’. As they have evolved, they have become an invitation to see not only references to the wider world but also the many art histories that there are. ‘You can have something that looks like a Guston eye, then pushes into a handprint and [then] feels like a weird kind of Louise Bourgeois breast,’ she says. ‘I’m not looking at [the marks] and trying to do these intentional things, but as you work, [references] are always coming up – you know, it can make you think of a particular artist.’

This lack of intention is something Mehretu finds, in her word, ‘liberatory’. In her hands, the novelty and the freedom of the gestures becomes political. ‘The language at hand is not enough,’ she says, ‘when you need to build something on the periphery, or to have some way of speaking, to invent something else.’ For Mehretu, the abstract marks take her away from what she calls ‘the power of the dominating culture’.

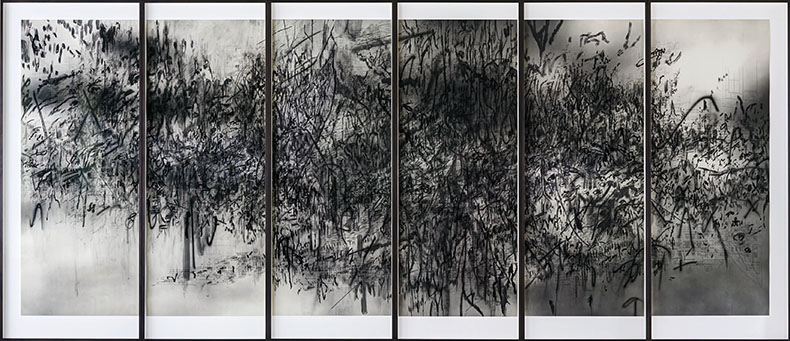

In her more recent work, the abstract mark-making has become freer both in appearance and in the way the marks are made. A lot of the marks are made not with a brush but with ‘airbrush and with my hand or with towels,’ she says. ‘It’s just this atomising of paint through air, a very different kind of gesture-making.’ But then the basis for these works is less rigid now, too. The architectural plans have receded and in their place are images of current affairs: the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the wildfires of California, the burning of Grenfell Tower. They don’t appear in crisp, recognisable versions of themselves but as blurred images, a layer of abstraction that immediately questions how these photographs are read.

TRANSpaintings (hand) (2023), Julie Mehretu. Photo: © White Cube/Theo Christelis; © Julie Mehretu

Mehretu, who collects images and projects them on to paintings, was prompted to shift her style partly by accident. Seeing one picture through an unfocused projector ‘really arrested me’. With the help of her long-time assistant Damien Young – ‘an amazing painter’ – she started working out how to recreate the blurred image on the canvas. An experiment with Photoshop resulted in something too technical, so they turned to the airbrush. It offered a light and a colour that became ‘interesting’ to Mehretu, but it also offered a ‘social ground’ for the work. In Mehretu’s terms, what results is ‘almost like the capturing of, the haunting of the image’.

With that haunting comes the ghost of the event itself – a spooky reincarnation of something that once captured the world’s imagination. This technique was deployed most recently in an exhibition at White Cube, Bermondsey, where the spectral presence even appeared in the title of the show, ‘They departed for their own country another way (a 9x9x9 hauntology)’. Images of the war in Ukraine and the events in Washington, D.C. on 6 January 2021 formed the background to the works.

The abstract marks are, in a sense, in dialogue with the image beneath. Collaboration at a more literal level is also part of Mehretu’s practice. While she goes into her ‘own space’ to paint, her way of working demands looking outside herself as well, whether that’s through travelling and conversing with other artists, or working together on projects. Her works at White Cube were shown alongside sculptures by the Iranian-German artist Nairy Baghramian, who even made special sculptures to hold and suspend Mehretu’s paintings. ‘I think that’s the space that I find really interesting: what happens when you put Nairy Baghramian holding, facing, hanging or dangling near one of my paintings, and what does that bring out in the paintings?’

Set designs by Julie Mehretu for Only the Sound Remains (2015) by Kaija Saariaho, commissioned by the Dutch National Opera, Finnish National Opera, Opéra national de Paris, Teatro Real in Madrid and the Canadian Opera Company

In keeping with this, when the show opens at Palazzo Grassi it will not be a monographic exhibition. Rather, it will include ‘other artists who were influential and important to me: very dear friends, and people that I have had a history of working with in some way, or a desire to do so.’ Artists appearing alongside Mehretu at the exhibition will include Tacita Dean, who filmed Mehretu in the act of printmaking; Paul Pfeiffer, with whom she runs a collective in the Catskills; and Baghramian again. When we speak, Mehretu is on her way to Venice, to go through the gallery space with the chief curator of the Pinault collection, Caroline Bourgeois.

One of the most moving encounters I had with a work by Mehretu was seeing Epigraph, Damascus (2016) as part of ‘W.G. Sebald: Far away – but from where?’ at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich in 2019. Seen in the context of Sebald’s photographs, which capture the intoxicating drabness of Europe and the intersections of complicated histories in brazen ordinariness, Mehretu’s work was compelling in a new way. It earned its right to insist on looking both up close and from a distance. The work traces the effects of war on the Syrian capital from many perspectives, inviting the viewer to hold the whole in mind at once.

Epigraph, Damascus (2016), Julie Mehretu. Courtesy Niels Borch Jensen Gallery & Editions, Berlin/Copenhagen; © Julie Mehretu

Mehretu’s collaborations have gone beyond the purely visual. Like her friend Tacita Dean, she has created backdrops for opera productions. An audience has a very different relationship with a work on stage than it does with a work on the wall of a gallery. ‘I feel like they’re slow, time-based experiences,’ says Mehretu. ‘The way that someone can sit in front of them longer and experience them differently – that’s something that fascinates me, and what can happen to the painting through that.’ But it also raises another sort of question. Mehretu declares ‘a steadfast commitment [to] and interest in abstraction’. While I was revisiting her work, however, I began to wonder just how abstract the paintings are. They use a language of abstraction but it’s never fully free of references to the world around it. Could this be about a different way of looking, as much as a different way of painting?

Mehretu upends my question. ‘I think that there isn’t this binary between representational work and abstraction. It’s much more blurry and messy […] I’m interested in that blurry part.’ I realise that’s the bit I like too, moving between the different registers as a viewer and seeing an artist taking on the different registers of the world we live in. To do it properly is a collaboration between viewer and artist that requires each to know what they are doing. Maybe then they can find a way through that makes sense.

‘Julie Mehretu’ is at Palazzo Grassi in Venice from 17 March to 6 January 2025.

From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.