The first thing you encounter in ‘Action-Reaction: 100 Years of Kinetic Art’ is a full-size version of Heinz Mack’s Mechanisches Ballett (1966–2015). Six chrome towers, capped with crowns, revolve ponderously in a mirrored room. Visually austere but nodding to Fernand Léger’s altogether more zany Ballet Mécanique (1924), the piece – which was conceived in 1966 but until 2015 existed only as a model – is indeterminate in its playfulness. It sets the tone for the rest of this dense, enjoyable and slightly chaotic show.

On the evidence here it is apparent that the category of ‘kinetic art’ suffers from something of an identity crisis. Is such work best exemplified by grand, physically interactive pieces (installations like Jesús Rafael Soto’s Pénétrable de Lyon [1988]: long strands of what looks and feels like half-cooked spaghetti through which you are invited to walk, or the calming, colour-flooded rooms of Carlos Cruz-Diez’s Chromosaturation [1965]; or Yayoi Kusama’s Invisible Life [2000–11], a corridor of mirrors which distort your reflection as you pass between them) of the kind beloved by urban developers and museum curators intent on promoting user participation? Or is it, as in the work of Bridget Riley and her many imitators, a more cerebral, restrained endeavour: a way of drawing attention to the sometimes vexed relationship between the eye and the wider world?

This confusion is reflected in the origins of kinetic art itself. The earliest use of the term was in Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner’s constructivist Realistic Manifesto (1920), in which they called for a new ‘Great Style’ in which ‘kinetic rhythms’ would be used ‘as the basic forms of our perception of real time’. A less acknowledged antecedent is the work of the horologists and automata makers of 18th-century Europe, who were able to render in mechanical forms the organic movement of birds, fish and heavenly bodies.

Le Prisme (1965), Nicolas Schöffer

The best-known pioneers of 20th-century kinetic art – László Moholy-Nagy, Marcel Duchamp and Alexander Calder – were, like Léger, influenced by the possibilities provided by the cinema, but also by popular optical illusions and puzzles. Along with Walter Ruttmann and Kurt Schwerdtfeger, some of whose films are shown here, Moholy-Nagy was quick to recognise the potential of the cinematograph to create moving abstract works. Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs – small patterned discs designed to be animated on a turntable – have a more homespun feel: they look like Edwardian optical curiosities (it is a great shame that those on display in the Kunsthal are left un-animated).

Calder spoke grandly of ‘composing motions’ just as one might compose with colours and forms, but he also was enthralled by the sheer fun of automata. During the 1920s he toured Europe and America with Cirque Calder (1926–31), a model circus whose performers were made of wire and rubber and animated by turning little handles. But it is now his mobile sculptures – one of which is on display in the Kunsthal – that most people still think of when you mention kinetic art.

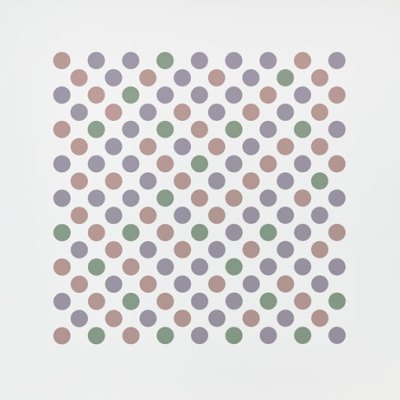

What might be termed the ‘second wave’ of the movement emerged during the 1950s and ’60s, resulting from a growing interest by artists in optical science and the psychology of perception. In the work of Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley and Wolfgang Ludwig, kinetic art was stripped of its mechanisms, and a divide opened up between those works that depended for their effects on real physical movement – animated sculptures using light, clockwork or electricity to achieve their effects – and ‘virtual movement’: paintings and sculptures that generated a kinetic experience in their viewers through optical trickery.

Those artists associated with Op art, in particular, ditched the Heath-Robinson homeliness of their predecessors in favour of stripped-down canvases which demonstrated kineticism on a flat plane by confusing the eye with contrasting colours and lines. Palettes became monochrome; effects depended not on the workings of gonzo machines cobbled together in studios, but on the relationship between the individual viewer and the canvas, mediated by visual phenomena alone. This retreat into minimalism is evident here in works by the Op art artists, but also by contemporary painters like Philippe Decrauzat, whose Slow Motion (2011) pays homage to the mainly monochrome palette of Bridget Riley, and Iván Contreras-Brunet, whose three-dimensional canvases, dressed in textured wire, invite you to look but never to touch.

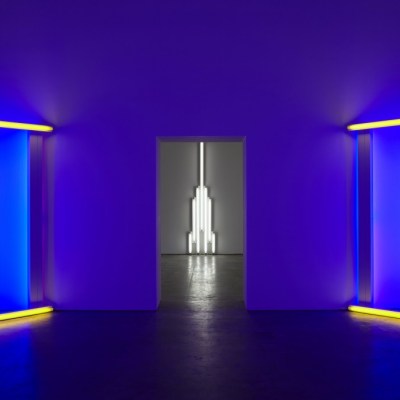

Untitled (in honor of Harold Joachim) 2 (1977), Dan Flavin. Collection FRAC Grand Large – Hauts-de-France, Dunkerque. © ADAGP, Paris

‘Action-Reaction’ does not pretend to offer a comprehensive history of kinetic art, or even of its last 100 years (perhaps such a thing is impossible). Instead the show is organised into 12 sections with titles such as ‘Light’ ‘Rhythm’ and ‘Immaterial’, some of which are more coherent than others. Sometimes the comparisons are illuminating: pairing Giacomo Balla’s Compenetrazione iridescente n. 7 (1912) with Dan Flavin’s Untitled (in honor of Harold Joachim) 2 (1977) in the ‘Light’ section tells a coherent story about how an interest in isolating colour from the bodies that might emit it developed through the century. The ‘Cosmos’ section, bringing together work by Liliane Lijn, Yaacov Agam, Gyula Kosice, and Julio Le Parc is less successful, and jarring in its kitschiness. Hugo Demarco’s Structure animée à déplacement continuel (1959–67) is like a cheap planetarium of rotating spheres highlighted by ultraviolet light, where Le Parc’s intensive and immersive work, with traces of filigreed light revolving on a wide circular screen, is astonishing in its overwhelming delicacy.

It is individual works rather than groupings that linger in the mind. My favourites were those pieces where movement and mechanism become part of an integrated whole: Roger Vilder’s wonderful Triangulation (1969), six white springs fixed to a slowly moving bicycle chain which winds slowly around a black board, stretching and compressing the springs to draw geometric shapes as it goes; or Nicolas Schöffer’s Le Prisme (1965), a scaled-up kaleidoscope where the play of light and shape is accompanied by a frantic whirring and rattling; or Pe Lang’s Moving Objects nº 1753–1754 (2015), a series of taut white strings stretched between a frame along which small black discs dance like birds on a telephone wire, or ants walking along a branch. In these it is a delight in making things, and in making the world animate through them, that is celebrated.

‘Action-Reaction: 100 Years of Kinetic Art’ is at the Kunsthal, Rotterdam, until 20 January 2019.

From the November 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.