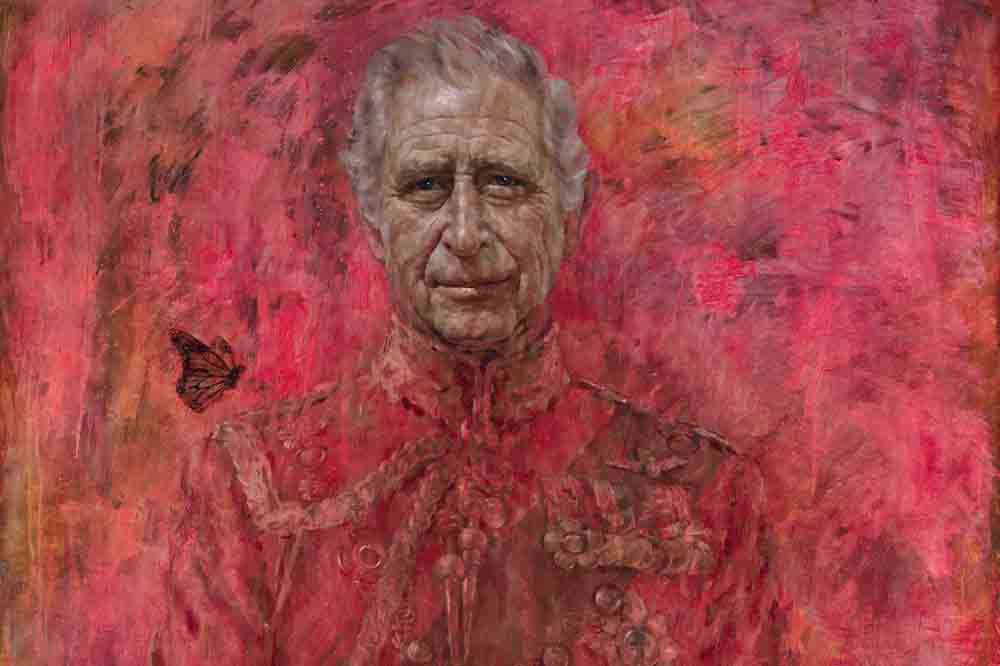

There are two things you can reasonably hope for from a contemporary portrait: one, that it look like the person it represents; and two, that it not be unbearably naff in doing so. Does Jonathan Yeo’s newly unveiled portrait of King Charles III look like him? Yes, it does. Charles’s face is there in all its benign, constitutionally limited glory: a gentle smile at the corner of his mouth and, if you will permit me, a little something deeper behind the eyes – the burden of the role, perhaps? Fans of the king’s generously proportioned digits may also approve of the way these have been rendered, gently curved around the hilt of his sabre. The whole thing is almost as like him as a photo – but the clever thing is, it’s not a photo. Viewers of a certain persuasion will see both the immediate likeness and whatever depth they wish to perceive.

Portrait of King Charles III (2024), Jonathan Yeo. Courtesy Philip Mould & Company; © the artist

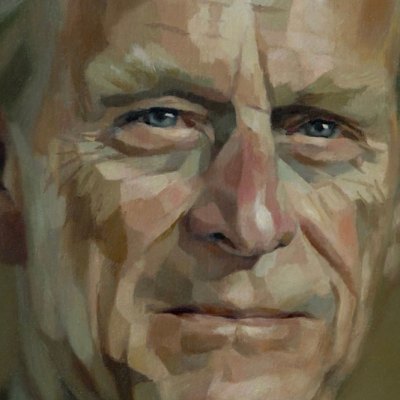

It would be churlish to deny that Yeo is a rather brilliant portraitist. When it comes to faces, his stock in trade alternates between glossy photorealism and neutered Lucien Freud, Yeo’s blunt gestural strokes housebroken until they resemble an early 2000s Photoshop ‘paint’ effect applied to a photograph. For the former, see his glassy vision of Nicole Kidman; for the latter, look no further than his take on the late Duke of Edinburgh – a painting that comes complete with the illusion of a portrait lens’s bokeh and shallow depth of field. Yeo is very, very good at both styles. Don’t Philip’s eyes just twinkle; doesn’t Rupert Murdoch look rather affable, avuncular even?

Whoever his subject, Yeo inserts two things into every painting: first, a standing reminder that this is all just paint, you know; and second, a little something that, with all the cognitive force of a brick between the eyes, will make you think.

For the painterliness, you are never left searching. Yeo is fond of leaving the artefacts of composition in there – gridlines and outlines – and of leaving things artfully unfinished to remind the viewer just what blankness these illusions must be summoned out of. Ostentatiously worked-over, the grounds strain towards Abstract Expressionist emotional depths via Monet-ish watery reflections.

For the thinking, here is Yeo himself with a head literally full of gears, calling himself Dr Futurity. Here is the unrepentant Tony Blair, with a look of non-specific mournfulness and a scarlet Remembrance Day poppy leaping from his monochrome suit. In effect it is not unlike extremely high-end fan art. There is another world in which a parallel Yeo is not paid at all, but sends his work unrequested to his favourite celebrities. Dear Cara Delevingne, please accept this steampunk portrait of you looking melancholic as a token of my admiration.

In the royal portrait, abstraction-Yeo and makes-you-think-Yeo have gone into overdrive. Much has been made of the redness from which Charles emerges. Social media currently seems split over whether it looks more like the blood spilled over centuries of British imperialism or the fires of hell – with one conspiracist contingent claiming that if you duplicate and mirror the painting you can see the face of Satan. In reality, it is all rather pink – less likely to make the multitudinous seas incarnadine than decorate someone’s nails, and, despite all the appearance of work, slightly thin and flat. But it does the job: ‘Look at all the brushstrokes … wow,’ said one of the small group of admirers inspecting the portrait beside me at Philip Mould’s showroom on Pall Mall. Painterliness, tick.

Philip Mould standing with Portrait of King Charles III (2024) by Jonathan Yeo. Courtesy Philip Mould & Company

Thinking, meanwhile, is covered by the appearance of a butterfly – a monarch butterfly, as a symbol of kingship and the king’s dedication to environmental causes. While the ceremonial medals and military dress uniform fade beneath the welter of brushwork, the butterfly leaps out. Do not get distracted by the fact that monarch butterflies do not actually inhabit Britain – just go with it.

If this all sounds snobbish and dismissive, it should not. Is this a good royal portrait? The question is immaterial. It is neither good nor bad: it is perfect. The truth is that this is precisely what royal portraiture gets to be in the 21st century. This is a portrait that is to art what a constitutional monarchy is to kingship. Hollow, vital, powerless, anchoring, dreadful, lovely, outrageous, vaguely reassuring; quite nice if you are into that sort of thing.

Jonathan Yeo’s portrait of King Charles III is on display at Philip Mould & Company until 14 June.