From the February 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

There are several hundred pieces of historically significant jewellery and gems in Krishna Choudhary’s family collection, so it comes as a surprise that when I ask him to name his favourite, he answers with no hesitation: ‘The star sapphire.’ His eyes gleam as he moves his palm under a lamp to show me how the enormous 150-carat blue stone he is holding refracts the light through its curved surface into several dazzling stars.

‘It’s one in 10 million stones – at least. When my father found out about it decades ago he was so excited he would wake up at three in the morning and say, “I want it,” and my mother would say, “you can’t do anything about that now.” When he finally acquired it from a family in central India, he named it Krishna Blue.’ His son’s name, of course, but also that of the Hindu god who is often depicted as having blue skin. ‘It reminded him of divinity.’

It’s not just its size and presumable worth (like most of the collection, it’s never been valued) that sparks this passion in Choudhary. ‘There’s nothing else like it. I saw another star sapphire double its size – some dealers were offering it for millions – but it was dead to me, as good as a bar of soap. Once someone who came to see our collection saw it [the Krishna Blue] and immediately started crying. And I can relate to that sort of emotion, as can my father.’

We are seated in a haveli – a traditional manor house – in the northern Indian city of Jaipur sipping coffee. The building is home to a family business that has lasted ten generations, as well as to its astonishing collection of jewellery, gems and precious artefacts. The current iteration of the family firm is Royal Gems and Arts, established by Choudhary’s father, Santi, in 1988 to encompass the house, collection and gem trade. Choudhary has added his own touch to the family legacy, designing a small collection of jewellery himself that takes inspiration from the objects housed within this building and selling them to private clients under the brand name Santi, in honour of his father (a nickname he acquired in Italy in the 1970s, when locals couldn’t pronounce his actual name, Shrawan).

The facade of the Choudhary family haveli in Jaipur. Photo: Hunar Daga

Choudhary will be exhibiting his creations this year at TEFAF in Maastricht (15–20 March), alongside a few of the family’s historical pieces that show the context behind his work. These include some of their portrait diamonds from the 17th century, which encase miniature paintings behind a flat diamond, and a jali – a lattice form often found in Mughal architecture – carved out of a single piece of jade from the 18th century. Seen on their own, Choudhary’s designs are strikingly contemporary but when set alongside these old objects, the aesthetic references become clear in the symmetry, details, repetition and clusters of stones.

Nowadays Choudhary lives mostly in London with his wife, Vrinda – with whom he runs Santi from an office in Mayfair – and their two young children. He designs only a handful of pieces each year, as well as sourcing ‘special stones’ for his clients. Alongside that, he devotes time to telling the family’s story – and therefore that of Jaipur – whether talking visitors from around the world through his collection, nurturing relationships with institutions, curators and scholars who can shed light on its history, delivering talks or working with his father and his mother, Shobha, who run Royal Gems and Arts.

The Choudhary family, he tells me, settled in Jaipur, in the state of Rajasthan – famous for its forts and palaces – around the time the city was founded in 1727 by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh. There, his ancestor Choudhary Kushal Singh established himself as a banker; the family’s website displays a document, which it describes as a grant of approval from Jai Singh himself to establish his business with the Royal House, which entailed collecting taxes and revenue and maintaining law and order across an estate of eleven villages, as well as minting coins in the state’s name and lending money to the elite. Over time, Choudhary tells me, the family also built a flourishing jewellery business, drawing on their relationships with the city’s lapidaries, goldsmiths and enamellers, as well as the royal workshops – thereby also establishing the collection of treasures that they still hold today.

The haveli, the home of Royal Gems and Arts, was built in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and decorated with gold, vegetable dyes and varnish. Photo: Hunar Daga

This continued along fairly traditional lines until Krishna’s grandfather died in 1966. Santi, only nine years old at the time, took over the family business by the age of 13 and then, aged 16, travelled to Italy on his own, where he met craftspeople and collectors in Europe and beyond. As the family’s trade became more international, Santi’s personal passions drove him to expand the collection of jewellery and gemstones he’d inherited and to open up dialogues with museums around the world. Today, the family lends items from the collection to international institutions such as the V&A in London, the Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

This scholarly element of the work is particularly important to Choudhary now, but he didn’t initially gravitate towards the family trade. ‘I wanted to go into hospitality and I also had an interest in art, so I went to study for a diploma in Islamic and Indian art history at SOAS university in London in 2010.’ Visiting museums as part of the course, he discovered objects like the ones he had grown up around being revered and handled with gloves. This gave Choudhary a new perspective on what he’d previously taken for granted and a desire to learn more. He went on to study gemology at the Gemological Institute of America in Carlsbad, California, which is the body that created the International Diamond Grading System (based on cut, clarity, colour and carat weight).

While his father worked by instinct – ‘he talks a lot with his eyes, they’re very expressive of his passion’ – Choudhary now brings a new dimension of scholarship to the collection. ‘I used to ask him, “why is this piece beautiful?” And he would say, “it just is.” Now I can put it into words.’

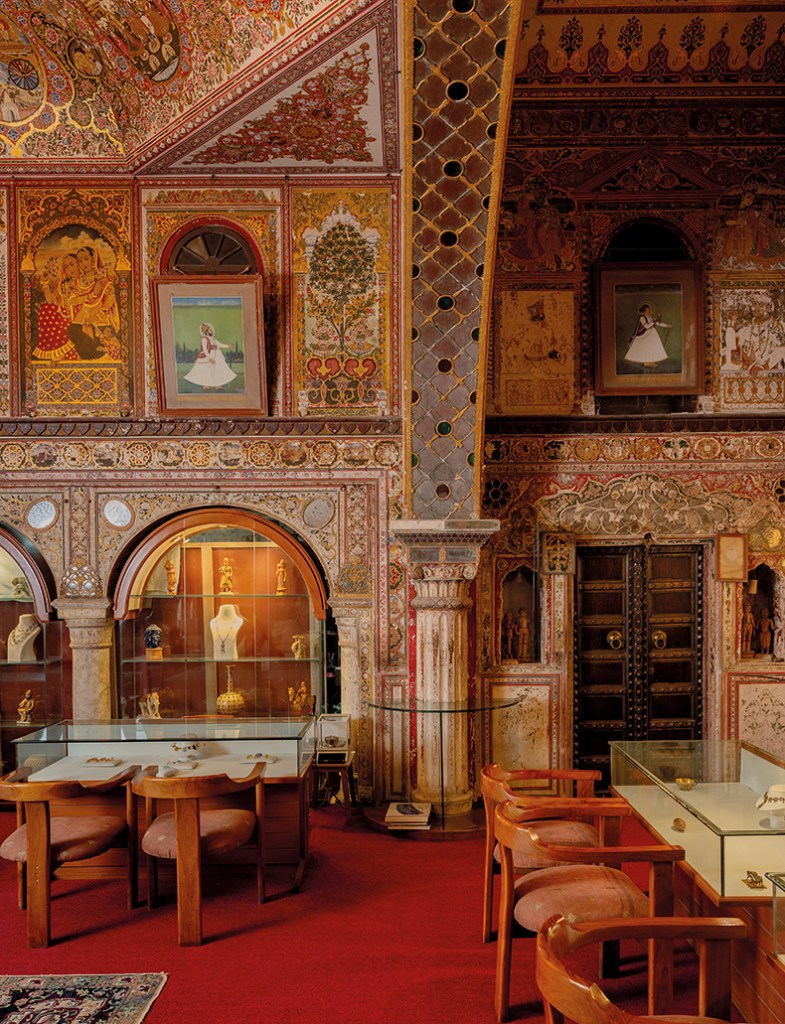

Saras Sadan Haveli, the house built painstakingly between the late 18th and early 19th century, is just as much a part of the family’s collection, a museum-like capsule of art inspired by the Rajput dynasties, which long ruled kingdoms across Rajasthan. The building’s pale front facade is painted with colourful motifs and figures. Inside the diwan-i-khas – the central hall – ornate frescos on the ceiling depict Hindu gods and goddesses, from Vishnu, the preserver, and Shiva, the destroyer, to Laxmi, the goddess of wealth and power, and Saraswati, the goddess of learning and music. Elsewhere are images of women dressed in the fashion and jewellery of the time and scenes of everyday life, including a horseman, a cobbler and a woman churning milk. The gold, vegetable dyes and varnish still gleam after 150 years, but restoration work has been essential – including waterproofing the outside of the building to stop moisture seeping in.

The restored central hall of the Krishna family haveli, which shows images of women in fashionable 19th-century dress. Photo: Hunar Daga

As a child, this heady environment seeped into Choudhary’s consciousness and now inspires his contemporary designs. ‘It seemed like an Aladdin’s cave,’ he says. ‘There are so many rooms, and you find objects sitting in corners everywhere. The mirror work and paintings resemble enamelling.’

The heritage building is open to the public, though the family encourages appointments rather than drop-ins. Visitors enter to find a circle of display cabinets around the edge of the room, each of which has a lamp and chairs around it to allow you to examine its contents. The really special items aren’t on show, though – they emerge from a more secure location behind the scenes. One by one, Choudhary shows me the goods, revealing each item and describing the materials and techniques used to make it, as well as its possible origins. The family owns about 300 pieces in total, he estimates, including jewellery, daggers and stones – with a particular emphasis on the Mughal era. I dare not touch anything, but my host dives right in without gloves. ‘They’ve survived this long,’ he says casually.

We examine a seemingly endless series of objects – each more dazzling than the last. A 19th-century diamond and red enamel chapka (head ornament) from the provincial courts of the historic kingdom of Oudh, with shapes of fish, a symbol of fertility and prosperity, on both the visible and hidden side. Earrings set with the figure of Yali, a legendary creature with the head and the body of a lion and the trunk and the tusks of an elephant, from south India – estimated to be from as early as the 13th century. A pair of 17th-century vanki armbands engraved with the face of Kirtimukha, a monster from Hindu mythology, in gold and gems. A 17th-century golden wine goblet set with diamonds, emeralds and rubies, an example of work from the early Mughal courts. A 19th-century jambiya (Omani style short curved dagger) handle ablaze with diamonds, emeralds and rubies and enamel, commissioned in India. An enamelled 17th-century sword hilt, with diamonds set and cut to protrude, rather than to be sharp and flat as has now become the fashion. A pair of 19th-century ornamental bullet cartridge boxes for royal hunting parties. An 18th-century turban ornament made of a rare flat spinel, a large red stone mined in Tajikistan and Afghanistan – with a back that depicts birds, elephants and flowers in multicoloured enamelling.

A 19th-century diamond and red enamel chapka head ornament from the kingdom of Oudh. Photo: courtesy Santi

There are many examples of the kundan technique, where gems – from Golconda diamonds to Colombian emeralds to Burmese rubies and sapphires – are mounted on and set between pure 24-carat gold, as well as enamel work (meenakari). In many cases, the side that’s not visible when worn is as elaborate as the other. ‘It’s a beautiful concept – a dialogue between the craftsman and the owner; your own little secret,’ Choudhary says. ‘It’s always fascinated me that somebody would put so much effort into something that would be hidden for its lifetime.’

The exact provenance, dates and details must be taken with a pinch of salt, he is careful to say, his scholarly training shining through. ‘It’s stupid for anybody to say anything is exact.’ All he will say is that the workshops of the royal courts – in particular, Mughal rulers such as Jahangir and Akbar, who prided themselves on nurturing craft, culture and beauty, and received precious stones from traders from as far afield as Europe and South America – produced an abundance of jewellery and precious objects in their workshops. The pieces in their collection, he says, resemble ones pictured being worn by important figures of the time.

A 19th-century jambiya curved dagger with diamonds, emeralds, rubies and enamel. Photo: courtesy Santi

Far from being a frustration, this element of the unknown appeals to him. ‘The beauty of this field is that there’s always some sort of mystery, and you have to connect the dots with a sense of history and some common sense – for example, the jade being polished or stone cut in a way that was done in a particular century, or the geographic origins of the colours used in the enamel. I love the speculation.’

Having inherited a love of collecting from his father, Choudhary continues to acquire new pieces. ‘It’s like an addiction,’ he says. ‘I can relate to my father waking up at three in the morning to think about stones.’ A recent stand-out acquisition of his own was a Mughal spittoon, with an incredibly thin rim – again, carved out of a single piece of jade – which he bought based on a photo alone. ‘I was afraid to tell my father because I thought he’d be mad that I bought something of such significance [without seeing it in person], but he said it was the best jade piece in our collection. It’s phenomenal to have carved it from one block of jade, which is the second-hardest stone after diamond.’ Choudhary has also branched out into collecting contemporary art – he sits on the Tate’s South Asian acquisition committee – though similar sensibilities are visible in these acquisitions, including paintings by Korean artist Minjung Kim, whose ink on paper works depict abstracted, repetitive shapes that resemble dreamy landscapes and natural forms.

Pair of disc earrings designed by Krishna Choudhary for Santi, each centred on a round old-mine diamond, pavé-set diamonds in platinum. Photo: courtesy Santi

Today, Choudhary says, the skills involved in making works of such high quality as his historical pieces have largely been lost, as nobody has the patience to wait as long as it takes. Surprisingly, his own designs are made in Italy, in the workshops with which his father first built relationships. Choudhary’s collectors are also mostly outside India, and he says that many are regulars. His own works strive to take influence from the Mughal era, and to use the kind of heritage gems that he has always been fascinated by, but to infuse them with a new aesthetic. For example, a titanium bracelet, designed to resemble the pattern of an abstracted Mughal carpet, is set with ten historical spinels, surrounded by baguette diamonds – and is inspired by an early 20th-century turban ornament. A ring set with an 18th-century pyramid-cut emerald resembles one worn in a painted portrait by the last Maharaja of Indore. Meanwhile, a pair of flat round earrings, each with a round old-mine diamond in the middle, are covered in a repetitive chevron pattern.

TEFAF will be an opportunity to reach new buyers for his own work, as well as introducing a whole new set of people to the family’s collection. When it comes to the latter, though, commerce is not in play – particularly when it comes to the precious star sapphire. ‘For my father, this object is like a son. We have promised never to sell it: it’s in our permanent collection, never to be touched.’ It isn’t even lent out to exhibitions. What is the reason for collecting these things that never get seen? ‘It’s like they are your children – you admire them every day,’ Choudhary says. There’s no need for anyone else’s validation.

Krishna Choudhary photographed in his family’s haveli in Jaipur in December 2024. Photo: Hunar Daga

From the February 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.