From the October 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

On the hottest day of the year so far, in a cool studio that feels like a refuge from the humidity outside, Liliane Lijn is turning up the heat. One half of the former warehouse in Harringay is full of small industrial machines, large work tables and any number of crates stacked on shelves up to the ceiling. But the other half, a shady space before we get to the artist’s office and the courtyard outside, is much emptier than usual. Most of the whirring poem machines, revolving cones and the other forms of motorised sculpture that normally live here are in Munich for the rest of the summer in ‘Liliane Lijn: Arise Alive’, a show at the Haus der Kunst, which moves to Mumok in Vienna in November (15 November–4 May 2025) and to Tate St Ives after that.

Here in north London in July, Lijn is trying to find switches and remote controls to wake the creations that have been left behind. We stop in front of a plinth for a bronze bust comprising a torso and head attached to each other by an armature. The torso, which emerges from a stack of mica fanning around it like a spiral staircase, is split vertically down the middle. Above a ruff of a stabilising collar sits a cracked head with expressionless slits for eyes. Expressionless, that is, until Lijn turns on a gas flame that shoots up the centre of the bust and exits via the eyes and cracks in the skull. The bust is made of patinated bronze, the central section matte black because of the flame: ‘It’s what we’re all made of – carbon – and it’s what we’re all trying to get rid of,’ Lijn says. Literally so here, since the carbonised material accumulates before eventually dropping off. Lijn moulded Lilith (2001), a ‘selfportrait with fire’, when she became interested in looking at herself, she tells me, in the late 1990s. With Lilith and other works like it, ‘The main thing is that they’re not moulded in one piece, because they’re moulded in fragments, I had to put them together almost like a puzzle.’ If we don’t speak of the significance of Lilith – a sexually voracious demon of Mesopotamian origins who figures in Jewish and Christian mythology as the unbiddable first wife of Adam – this is because I suggest to Lijn that the bust is like a human Bunsen burner. I seem to be letting both of us down, but her reply is brisk and matter-of-fact: ‘Well, we are hot inside. We do develop heat.’

Although we have begun with matter rather than meaning, it soon becomes clear that Lijn, who is now 84, is as interested in testing materials as exploring myths and archetypes. The version of ‘Arise Alive’ I saw this summer, curated by Emma Enderby and Teresa Retzer, presents works made between 1959 and 2009 and conveys the range of Lijn’s interests while suggesting, not too didactically, how they cohere. By the entrance to the exhibition at the Haus der Kunst was a work called Vibrographe (1962), which consists of two metal drums fitted with motors, covered in Letraset lines and mounted in a box. As the motors move the drums in opposite directions, the lines start to blur, creating coloured patterns and after-images. Lijn is often credited with being the first woman to put a motor into an artwork, a curiously narrow commendation for an artist whose interests are so various. But if an art-historical pigeonhole were needed, Vibrographe and the Poem Machines Lijn made in Paris in the early 1960s make her a member of the kinetic art movement. In Munich, however, once the visitor was past Vibrographe – an isolated work on a wall – the exhibition restarted with a drawing called The Beginning (1959), which represents a real turning point in Lijn’s life.

Get Rid of Government Time (1962), Liliane Lijn. Collection of Stephen Weiss, London. Photo: Maximilian Geuter; courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London/Piraeus; © the artist

Lijn was born Liliane Segall in New York in 1939, four months after her Russian-Jewish parents left Germany and settled in the United States. Her upcoming memoir, Liquid Reflections, which will be published by Hamish Hamilton in the spring, begins with an acknowledgement of luck: ‘I am alive because in 1923 my grandfather bought a Cuban passport.’ When Lijn was 14, her by then divorced father and mother moved back to Europe – to Geneva and Lugano, respectively. Lijn went to the liceo classico in Lugano but was already determined to be an artist, which meant moving to Paris. In 1958, she began studying archaeology at the Sorbonne, but studying in French for her degree, even if she spoke it fluently, was daunting. ‘The interesting thing for me about that period was that, although it was short, it influenced my work as an artist.’ Lijn says. She lasted only six months at the Sorbonne, but her brief studies left her with a lifelong love of ancient art and myth.

By the time Lijn made The Beginning, she had ‘spent quite a long time drawing’. (At first she took up painting, but ‘the minute I saw what people were really doing, I realised that I needed to learn how to draw’.) A meticulously executed crayon-and-ink composition that unfurls across the page, the drawing looks like a mappa mundi with the place names left off. For Lijn, it was an inner map: ‘I was creating a cosmogony and that was the world, my world. In a sense I was recreating myself. I’d been through quite a tempestuous love affair that was […] mainly abusive to my ego; I was totally deflated, and so when I did that drawing I felt that I was beginning.’ It was the sub-optimal boyfriend (Jean-Jacques Lebel) who first introduced the 18-year-old Lijn to Takis, a 33-year-old Greek artist who spoke poor French and resembled, she writes, Prince Myshkin, the ‘idiot savant’ hero of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. The parallels didn’t persist in her mind for long: it was Takis, she writes, who was the first person in Paris to take her art seriously. They would later marry and have a son, though not live together, and then divorce in 1970.

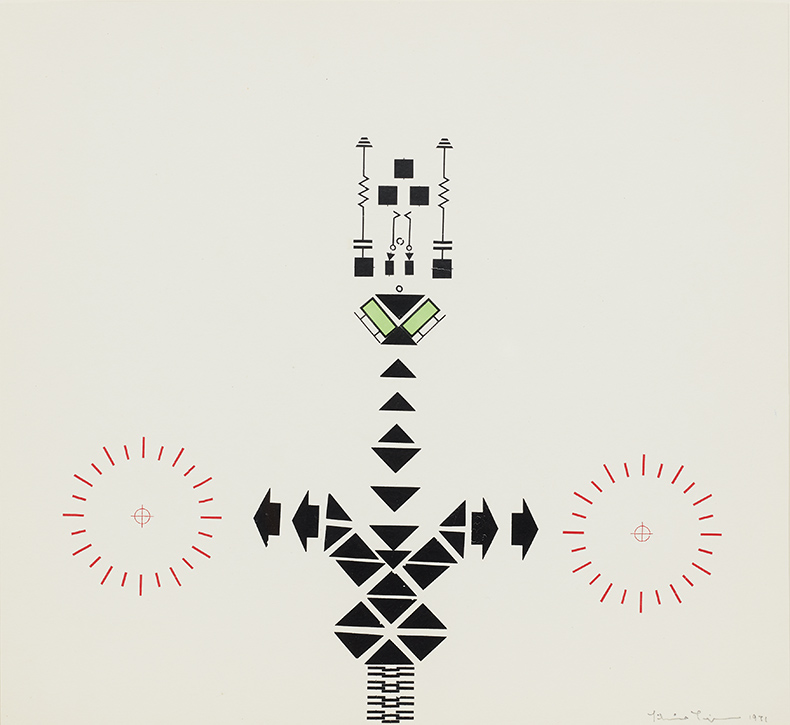

Neurographs: Electronic Goddess (1971), Liliane Lijn. Photo: Maximilan Geuter; courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali; © the artist

Lijn has spoken, more than once, about what it was like to be a very young woman in Paris in the late 1950s. Through the mother of her best friend, Nina Thoeren, she met André Breton, who was still holding court among those members of the Surrealist Group he hadn’t excommunicated. It’s no surprise that she and Nina ‘got very bored’ listening to the internal politics of an artistic groupuscule. (Poets, the Beats in particular, were much more interesting and a good deal friendlier.) Throughout Lijn’s memoir, which covers her life from ages 18 to 27, the sexism of avant-garde artistic circles is never far from our minds. (When she first moves to Paris, a painter friend of her father says, ‘For a woman, this is no career. What does she want to be an artist for?’) In such a hostile environment, it’s not surprising that the women who do succeed aren’t friendly, either. As Lijn tells it, when she met Meret Oppenheim, the Swiss Surrealist more or less ignored her. And so it generally went: ‘Not always but generally,’ Lijn writes, ‘when I was introduced to a woman they smiled and, with a tilt of their heads, turned away to speak with the man. It was quite different when I was introduced to a man.’

There is nothing so remote as the recent past. As I read the book after our first meeting, I wonder if I am reading other encounters too negatively. But when I ask Lijn why she is publishing this memoir of her early life now, her reply is blunt: ‘I feel that younger generations of women who are just coming up and are seeing a lot of younger women artists out there, […] they should remember that it wasn’t like that.’ There’s more to the book, of course, than this – and Lijn has deeper motivations. She has been writing the book, based on the diaries she kept in her twenties, for a long time. It can be seen as a much more literal sequel to Crossing Map (1983), an autobiographical work narrated through poems and drawings.

Although ‘Arise Alive’ is her biggest institutional show so far, Lijn is in no need of being discovered. She has always had well-reviewed exhibitions at the most forward-looking galleries and been valued by curators whose influence can still be felt in museums. Among the latter was Harald Szeemann, who in 1966 included her work in his ‘White on White’ show at the Kunsthalle Bern. ‘Your work is experimental and that’s interesting, Liliane, but for group shows, never bring small works,’ Szeemann advised her. Lijn tells me that she hasn’t always listened. Nor did she let the lack of interest shown by the career-making critic Clement Greenberg deter her. In the memoir, she passes on his advice, if it can be called that, ‘to come back to him after I turned forty, at which age he could take me seriously as an artist. As a woman, I realised, I would always be too young.’

What comes across at the Haus der Kunst is Lijn’s openness to new techniques, materials and influences, and to accurate information about the physical universe. After Vibrographe and before we get to other kinetic works, there are more drawings: small, meticulous ones in pen and ink (The Beginning) and larger ones in wax crayon, gouache and ink that hint at fantastical creatures and cloud formations (Sky Scrolls, 1959–61). In this first room we see Lijn leaving paper behind, at least for a time, to experiment with plastic. To make Fire Lines (1960), for instance, Lijn melted Tefonstift – a plastic stick used to wax skis – and drew coloured lines on to Perspex before burning them in with a small torch; for the Cuttings series (1961) she sawed lines into Perspex that cast shadows on to the back of the plastic sheets and appear to the eye as solid shapes.

Liquid Reflections/Series 2 (48″) (1968), Liliane Lijn. Photo: Maximilian Geuter; courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali. London/Piraeus; © the artist

It may seem, looking at Lijn’s work, that she is two different artists, representing two seemingly incompatible aspects of the 1960s. The first is inspired by Buddhism, by Jung, by Jung’s disciple and collaborator Marie-Louise von Franz (best known for her work on fairy tales and mythical archetypes) and by Robert Graves’s theories of ‘the white goddess’ in his book of the same name.

The second is a technical pragmatist, a dedicated reader of Scientific American who has followed developments in physics and collaborated with NASA and the Space Science Laboratory in Berkeley. In the early 1960s, what allowed her to move from drawing on paper to drawing on Perspex, for example, was a lucky discovery in New York: ‘This plastic company on Canal Street gave me part of their warehouse to work in and they said, “You can use all our machinery and help yourself to the materials,” so I just had this wonderful playground for a few months.’ This second Liliane Lijn was just as open to other kinds of chance encounters: the Tefonstift discovery came from convalescing at the same Swiss hotel where the French Olympic ski team were staying and befriending one of the skiers. (The memoir ends with Lijn preparing to leave Greece, where she has been supervising the building of a house and where Perspex is either impossible or too expensive to obtain.)

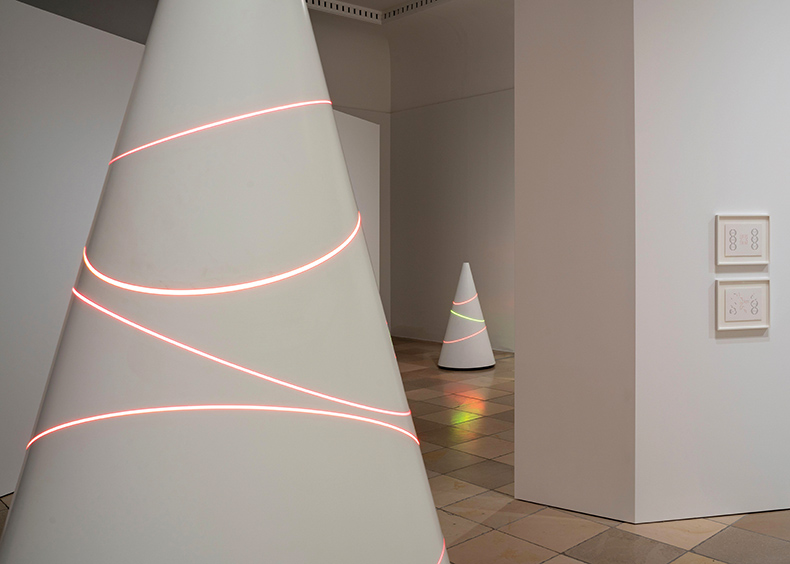

But, as Lijn says of the cones, columns and the work called Liquid Reflections (1968) for which she may be best known, ‘I actually make things at the same time, I don’t move on. I remember thinking that I was some kind of general, because I had all these different things I had to think about, and different people I worked with.’ If the sculptures have taken wildly different forms, Lijn’s preoccupations have remained the same: ‘I’m always interested in shadows and reflections. Most of my work is an interplay of shadows and reflections, colour, the spectrum is important.’

Installation view of (left) Lost Koan (2007) and (right) Three Line Koan (2008) by Liliane Lijn at the Haus der Kunst in Munich in 2004. Photo: Maximilian Geuter; courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London/Piraeus; © the artist

Both sides of the artist are expressed by cone-shaped sculptures called Koans. It was Lijn’s reading of The White Goddess that introduced her to the idea of a white conical mound of ash that was, according to Graves, sacred to the early Greeks and later domesticated by the Romans as the hearth. ‘I thought that was a very beautiful thing, because not letting the fire go out is not letting life go out.’

But as Lijn freely admits, she also just loved highway cones and how they varied from country to country. After her first attempt, Hiway Cones (1966), she started making them in Perspex and adding intersecting lines or applying words in Letraset, carrying on her cut-up experiments with the cylindrical Poem Machines and putting them on revolving record turntables.

If Lijn didn’t have enough in the way of preoccupations and obsessions, a third artist might be present: one who is interested in performance. The most striking works in this vein are the large-scale installations Woman of War (1986) and Lady of the Wild Things (1983), which comprise a performance piece called Conjunction of Opposites. In a darkened space, a nearly three-metre-high figure made of steel and aluminium begins to sing (it’s Lijn, who has a very expressive voice, singing) and opens her wings to reveal black, red and yellow plumage. As the wings of a second sculpture light up in response, dry ice begins to rise around Woman of War, who shoots a red laser beam towards it, thus ending what Lijn calls a six-minute-long ‘cosmic drama’, until the sequence begins again.

Installation view of Conjunctions of Opposites: Woman of War and Lady of the Wild Things (1986) at the Haus der Kunst in Munich in 2024. Photo: courtesy Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London/Piraeus; © the artist

It’s the culmination of the exhibition at the Haus der Kunst, but there are moments of theatre throughout the rooms. To spare their mechanisms and, perhaps, focus the visitors’ attention, the cylinders and cones all come on at set times. I double back several times to catch a particular one, though somehow miss Fidel Prism (1964) each time and can’t tell what effect the dematerialisation of Castro’s first name might have on me.

But the best example of what Lijn calls ‘art theatre’ is a private, impromptu performance the artist inadvertently gives me as I am on my way out of her studio. Passing a plinth covered in small cones, or Koans, of many colours covered in symbols – to some eyes, they look like party hats that witches might wear, but I keep the thought to myself – I am rewarded by Lijn turning the cones on. The symbols are Sumerian glyphs, she says. As they revolve, Lijn recounts the adventures of the goddess Inanna, known in other mythical systems as Ishtar, who keeps changing roles, outwitting her enemies, saving her friends and acquiring new knowledge. I ask Lijn if things end well for Inanna. ‘Things end well,’ she says, ‘though she goes to the underworld towards the end, because she’s kind of bored and wants to find out more.’ As I reluctantly leave Lijn’s realm, I find it hard to imagine her ever getting bored.

‘Liliane Lijn: Arise Alive’ is at Mumok, Vienna, from 15 November–4 May 2025. A memoir, Liquid Reflections, will be published by Hamish Hamilton next year.

From the October 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.