From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

A recorder and a bow carefully balanced across the neck of a rebec. A stone parapet. Three singers, two of whom beat time, fingers tapping on the ledge, while a central shaggy-haired singer plays the lute, his eyes downcast as he reads from an open score. The man on the right looks to the lutenist, but the woman on the left looks out beyond the parapet, engaging the viewer with a direct gaze. She is richly dressed with jewels at her neck and a delicately woven hairnet, with one hand resting on the lutenist’s shoulder. This painting in the National Gallery by Lorenzo Costa is today known as A Concert (c. 1488–90), but this scene does not record a public performance as such. Rather, it commemorates the rise of a new pursuit at the courts of Renaissance Italy in the last decades of the 15th century: cantare al libro, or sight-singing from a book. Indeed, while its subject has notable precedents in earlier relief sculpture by Luca della Robbia, the painting is generally recognised as the earliest example of a new genre of ‘concert’ paintings that emerged in northern Italy – particularly the Veneto – in tandem with the increasing popularity of this leisure activity.

A Concert (c. 1488–90), Lorenzo Costa. National Gallery, London

First recorded in a private collection in Bologna in the 18th century, A Concert has long been connected to the musical interests and artistic patronage of the Bentivoglio court in Bologna, where Lorenzo Costa lived and worked from around 1483 until 1507. At that time, Giovanni II Bentivoglio was the de facto ruler of the city, a position he held for nearly half a century, until he was expelled by Pope Julius II’s sack of Bologna in 1506. After the fall of his patrons, Costa moved to Mantua, where he replaced the recently deceased Andrea Mantegna as court painter to Isabella d’Este. Though the original Palazzo Bentivoglio was destroyed and its treasures dispersed, Costa’s extraordinary paintings for the Bentivoglio family chapel at San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna, including the altarpiece of 1488 that is his earliest dated work, go some way to conveying both the intellectual ambitions of patron and artist, and the relationship that Costa enjoyed with Bologna’s ruling family.

Costa’s Concert was almost certainly part of the largely lost decorations at the Palazzo Bentivoglio, probably in a studiolo or a music room. Surviving decorations from such interiors in palaces at Urbino, Gubbio and Mantua convey how these spaces were conceived, with painted or intarsia images in series. Costa’s painting would have been open to interpretation as an allegory of Harmony or Concord. As expressed in the writings of contemporary humanist Pietro Bembo, the form, metre and accent of music, like poetry, was considered representative of harmony. Whether accompanied by other representations of music-making, musical instruments or the liberal arts, the painting may have been part of a set of decorations. Musicians often performed from a high gallery, in church as well as in secular contexts, so the subject would have been appropriate set high up on a wall, or perhaps have functioned on its own as an overdoor – though the painting lacks a low vanishing point.

Virgin and Child Enthroned with the Family of Giovanni II Bentivoglio (1488), Lorenzo Costa. San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna. Photo: © Photo Scala, Florence, 2025

The new pursuit that Costa represents in his painting, however, was essentially private in its nature. Cantare al libro gained popularity with the rise of the frottola. These three- or four-part secular songs, often with instrumental accompaniment, were collected and copied in manuscripts commissioned by patrons such as Ercole d’Este at the court of Ferrara, or Isabella d’Este at the court of Mantua. Isabella’s canzioniere is a particularly beautiful surviving manuscript of this kind, which originally contained 100 three-voice pieces, with more pieces added later on folios that had been left blank. The book is designed to serve a group of performers playing and singing directly from its pages, with gilded voice-rubrics (symbols indicating instructions) and spaced-out staves, so that it would have been legible from several feet away. While the earliest frottole are found in manuscripts, they also appear in later printed anthologies, such as the Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, published by Ottaviano Petrucci in 1501, which was arranged so that four musicians could read from the book at once.

Frottole are also recorded in one of the most important manuscripts to survive from Renaissance Bologna, known as Codex Q 18, today in the Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale, Bologna. It attests to the musical interests and patronage of the Bentivoglio family (and can be heard in a recording made by the Speculum Ensemble in 2010). At just slightly smaller than A4 in its dimensions, the manuscript’s well-thumbed pages, smudges and corrections to errors in the score indicate its frequent use. Its contents were probably copied at around the same time by four different scribes, who may have included Giovanni Spataro, a choirmaster and composer whose hand is found in choir books associated with the Bolognese church of San Petronio, and, significantly, Ermes Bentivoglio, the youngest son of Giovanni II. More than half the manuscript’s compositions are unique and anonymous, but others can be attributed to known composers such as Josquin des Prez, a Franco-Flemish composer who worked throughout Europe, including at the Sistine Chapel and the court of Ferrara. Notably, eight compositions from Codex Q 18 have titles that allude to Bologna or the Bentivoglio family. ‘Deus fortitudo mea’, for example, a motto of the Este family, may record a piece associated with the marriage between Lucrezia d’Este and Annibale Bentivoglio, one of the major social events of late quattrocento Italy, while ‘Spes mea’, the motto of Ginevra Sforza Bentivoglio, is given as the title to a song without words.

The musical activities of the Bentivoglio family are further attested by another painting often attributed to Lorenzo Costa, which appears to commemorate members of the family making music together with professional singers and courtiers – including, it would seem, with Lorenzo Costa himself, whose name is inscribed on the hat of the long-haired man on the far left of the composition. Further inscriptions at the top of the painting purport to identify the singers. In the upper row, from left, are Bianca Rangona (née Bentivoglio), Antongaleazzo Bentivoglio, two professional singers and a woman named here as Caterina Manfredi, but possibly intended as Francesca Manfredi (née Bentivoglio). Below, the figures are identified as Lorenzo Costa ‘pitture’, a priest called Pistano, the youngest Bentivoglio brother, Ermes, in red, Bonaparte dalle Tovaglie, the maestro di cappella of the cathedral of San Pietro, Bologna, and Alessandro Bentivoglio, the third brother of the family, who holds the sheet of music. The appearance of the named Bentivoglio siblings broadly tallies with their likenesses in Costa’s altarpiece of 1488.

The Bentivoglio Family (1493), Lorenzo Costa. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

The presence of three Bentivoglio sisters here is particularly striking. A moral and cultural framework for judging musicality, particularly that of women, can be understood through The Book of the Courtier (1508) by Baldassare Castiglione, whose close relationship with Isabella d’Este, Costa’s future patron, makes his view particularly relevant here. Noblewomen received instruction in singing and playing, and at least some of these women were taught to read from notation: theorist and composer Pietro Aron recorded a list of women known for their musical talents, some of whom were noted for their ability to sight-sing as well as to accompaniment by a lute. Castiglione’s ideal noblewoman sang and played only on request, and with modesty. She did not use flamboyant ornamentation, a preserve of courtesans and professional musicians. The Bentivoglio sisters who sing with courtiers and professional musicians in the family portrait might be joined by their brothers, but ensemble music-making could still be a controversial activity for women at court.

The status of the painting remains mysterious. Whether it is a very damaged or incomplete work by Costa himself, or a copy after a lost painting or paintings by the artist, remains unknown. The purpose of the inscriptions is also unclear. The Bentivoglio family would have had no need for inscriptions to identify their relations and courtiers and they may have been added to record a memory of the sitters’ identities. Nonetheless, the painting seems to be significant as one of the first known Italian group portraits, as a visual record of cantare al libro at the Bentivoglio court – and as visual evidence of Lorenzo Costa’s participation in the social music-making of his patron’s family. Regardless of when the upper inscriptions were added, the text on the left-most singer’s hat would seem to confirm this as a likeness of Costa himself.

View of the studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, made in c 1478–82. Metropolitan Museum of Art

A comparison with the National Gallery’s Concert suggests that Costa painted himself singing in this painting too. A compelling likeness has been observed between his appearance in the family ensemble and the shaggy-haired central singer who accompanies the Concert group on the lute. It has also been suggested that this was not intended as a self-portrait as such, but rather as a convenient way to capture the expressions made while singing. With the painting displayed in the studiolo or music room of the Palazzo Bentivoglio, however, Costa’s presence in it could not have gone unrecognised by the Bentivoglio family and his fellow courtiers. Various attempts have been made to identify the other members of the Concert’s trio by comparison with the Bentivoglio family portrait. Most recently observed is the likeness between the young woman and the singer named as Bianca Ragone, and that between the young man and the singer named as Ermes Bentivoglio – whose hand is also identified as one of the scribes in Codex Q 18, the Bentivoglio’s music manuscript. Costa’s presence in two paintings so closely associated with Bolognese music-making proclaim his importance as a musician as well as a painter at the Bentivoglio court.

It is not known how or when Lorenzo Costa received his instruction in music. His artistic origins can be traced to Ferrara, where he was influenced if not trained by Ercole de’ Roberti, one of the leading painters of that city in the later 15th century. At that time, Ferrara was a centre of musical innovation. Ercole I and Alfonso I d’Este encouraged the intertwining of music with other arts. Music at the ducal chapel was led by Johannes Martini, a singer and composer who served the Este family for almost 25 years. Musical invention was by no means limited to the court, but took place in churches, monasteries and confraternities – as well as the city streets, where travelling musicians performed. Costa’s paintings also attest to his familiarity with the latest advances in the making of musical instruments. Indeed, he is recognised among musicians specialising in historical performance today for the unusual accuracy of his representation of instruments. In A Concert, the lute itself is a faithful representation of a five-course lute of the late 15th century, with its frets and decorative rosette painted with great attention to detail. The angels playing viols in his 1497 altarpiece for the church of San Giovanni in Monte in Bologna and his representation of lire da braccio in his paintings for Isabella d’Este’s studiolo attest to his familiarity with these instruments and how they were played.

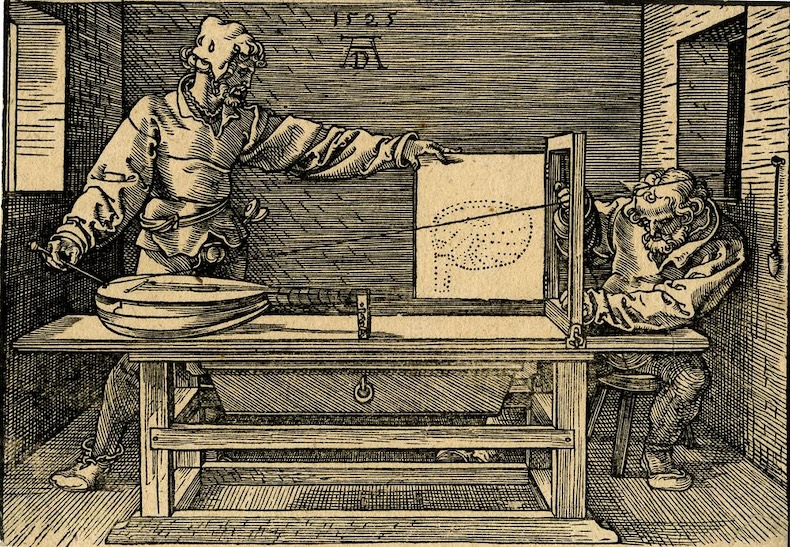

Illustration of an artist drawing a lute from Treatise on Measurement (1525) by Albrecht Dürer. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum

Whether Costa received his musical as well as artistic training in Ferrara, or whether this was a courtly skill he picked up later in Bologna, his ability as a sight-singer would certainly have been appreciated in the Bolognese court. One could even speculate that Costa’s musical abilities may not have been overlooked when he joined Isabella d’Este’s court in Mantua. Isabella was an excellent singer, and musical performance was certainly part of court life. Ensemble music-making was described by writers as an intimate and discreetly competitive game. A courtier’s ability to acquit himself well under pressure, in the company of his social superiors, would have enhanced his status, propelling him into new social settings with his musical patrons. For Lorenzo Costa, his musical talents may have raised him above the status afforded to a court painter, as his presence on the periphery of the Bentivoglio family portrait would seem to show. Such was the case for Leonardo, who was valued for his abilities as a lutenist at Ludovico il Moro’s court in Milan.

Costa’s portrayal in A Concert presents further evidence of his unusual standing as a painter-musician-courtier. While the painting is most probably intended as a decorative allegory, not a portrait, the inclusion of Costa’s own likeness would nonetheless have been recognised by his patrons and fellow courtiers. His eyes may be downcast to read from the open score, but here he is at the centre of the ensemble. There is also an extraordinary frisson in the presence of the young woman’s hand on his shoulder. The index finger of her left hand is slightly raised: she does not just beat time on the ledge; she drums it on the lutenist’s shoulder too. This physical intimacy may pass beyond the kind of contact permissible between a noble lady and a painter, however courtly. For Costa to use his own likeness in this way, his participation in this kind of court music-making must have been a relatively regular occurrence. This would perhaps not be so surprising if he was indeed very accomplished. As any chamber musician knows, one reliable singer or player can carry less confident participants with them and vastly improve the experience of every member of the group.

Intriguingly, the lutenist at the centre of A Concert once played an even more prominent role in the painting. Small adjustments were made during the painting process to achieve the composition that we see today. Most notably, the female singer was once turned further towards the lutenist, with her eyes directed towards him, mirroring the gaze of the young man on the right, who looks to the lute-player for his lead. In this earlier version of the painting, the lutenist was presented as the ensemble’s leader. In the changed composition, however, Costa directed the woman’s gaze outwards, asserting her authority within the group and diminishing that of the lutenist that he himself modelled. The ensemble in the painting as we see it today has no leader as such. Each member of the trio – including the lutenist – holds their own. This might be an allegory of harmony, but it is also a radically equal music, in which a painter might, through his ability as a musician, achieve momentary harmony with his noble patrons through song.

Music (1470s), Justus of Ghent. National Gallery, London

From the March 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.