From the November 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1939, the psychiatrist Walter Maclay found eight coloured drawings in a Notting Hill junk shop. They all show cats. A sepia tabby presents its profile against a background of softly coloured leaves; another with long hair and saucer eyes is apparently suspicious of something just out of sight. The third, more firmly outlined, is on the prowl, against a jagged, electrical force field that seems to emanate directly from its dark orange fur. The remaining five, densely patterned, symmetrical, and coloured with the luminosity of stained glass, are virtually abstract – except that they all coalesce around a pair of pointed ears, a grinning mouth, and two twinkling eyes.

Maclay quickly recognised these drawings as the work of Louis Wain (1860–1939), a popular but financially unsuccessful commercial illustrator, who had died in July of the same year. Wain is played by Benedict Cumberbatch in a biopic released in January 2022 in the UK, which explores his scandalous marriage to his sisters’ governess, her early death from cancer, his subsequent rise to fame as a ‘cat artist’, and the overwhelming and increasingly violent delusions that ultimately led to his admission to the pauper ward of Springfield mental hospital, Tooting, in 1924. The eight drawings found by Maclay, popularly dubbed the ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’, were probably produced after Wain was institutionalised. They are now in the collection of the Bethlem Museum of the Mind and remain, for many, emblematic of ‘asylum art’. At the end of the film, The Electrical Life of Louis Wain, they appear in a Hitchcockian dream sequence, melding and metamorphosing into one another, reflecting Cumberbatch’s own comment, in Chris Beetles’ new book on Louis Wain’s Cats (2021), that, with Wain’s story, ‘everything seems to blur in a kaleidoscopic mess of electricity, cats, love, loss of control and chaos’.

Kaleidoscope Cats I–VIII (1920s/30s), Louis Wain. Bethlem Museum of the Mind, London. All photos: © Bethlem Museum of the Mind/Bridgeman Images

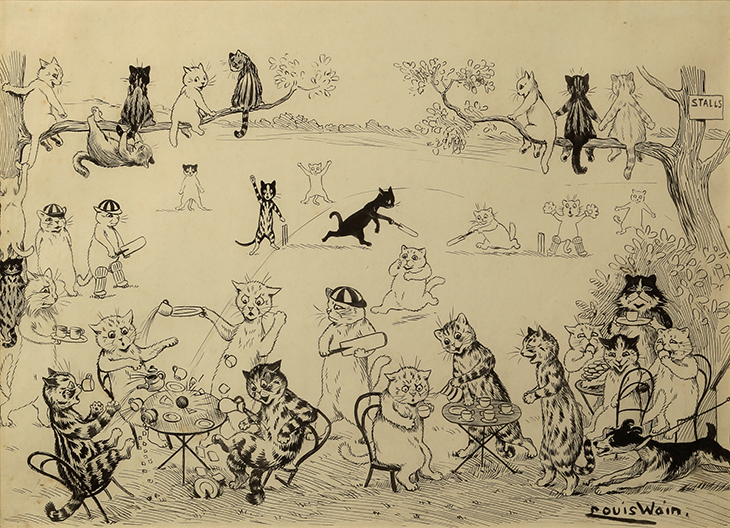

Wain was at his peak from the 1880s until the early 1900s. His anthropomorphic cats, often brightly coloured and usually engaged in fashionable contemporary activities – at the seaside, playing golf, going for a drive, taking tea – were widely circulated in annuals, illustrated newspapers, postcards and magazines. Their popularity coincided with the expansion of the commercial print market and development of colour reproduction, and it is estimated that during this period Louis Wain regularly painted some 600 cat pictures a year (along with occasional dogs and birds). Unfortunately, his father’s death in 1880 had left Wain the main breadwinner for his mother and five sisters – and he had neglected to copyright his images. As a result, the family remained in near penury even as Louis Wain’s Annuals were becoming ubiquitous in family homes. It was only after Wain was ‘discovered’ in the Springfield paupers’ ward in 1925 that a national campaign raised the money to transfer him to the more salubrious Bethlem Royal Hospital, then in Lambeth, south London, and finally in 1930 to Napsbury, near St Albans.

Even before his breakdown, Wain’s delusions and obsessive theories – including the belief that cats’ fur generated electricity, and that, like magnets, the creatures habitually faced north – marked him as an eccentric. In 1896, as part of a profile in The Idler, the journalist Roy Compton watched in amazement as Wain, ‘too true an artist to have professional affectations or conceits’, dashed off a cat with ‘marvellous […] rapidity and ease’, all the time spouting the conviction that ‘our English cats are slowly but surely developing into stronger types […] the face becom[ing] condensed, as it were, into a series of circles’. Compton’s piece was accompanied by a composite photograph showing Wain’s head, in profile, emerging out of a crescent moon. The Idler imagines him as a dreamer with his head in the clouds, but Compton’s description of Wain’s genial peculiarities also seems designed to echo the ancient idea that creativity is cousin to madness – Shakespeare’s characterisation in A Midsummer Night’s Dream of ‘the lunatic, the lover and the poet […] of imagination all compact’.

Louis Wain at his drawing board in the 1890s. Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

In this vein, 19th-century readers might also have thought of the painter of fairies and fantasies Richard Dadd (1817–86). In 1843, this young artist of promise had precipitously disappeared from the art scene when, apparently in a fit of ‘monomania’, he had murdered his father whom he believed to be the devil in disguise. ‘No living artist possessed a more vivid or delicate imagination,’ the monthly journal Art-Union had pronounced, ‘and there is no doubt that the excess of this quality predisposes to the disease which has triumphed over him.’ Like Wain, Dadd was resident for a time at Bethlem Royal Hospital, though as a murderer he was confined to its wing for criminal lunatics. He continued to paint for the next 40 years: intricate oils and watercolours such as Contradiction: Oberon and Titania (1854–58), an illustration to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Sketch of an Idea for Crazy Jane (1855), in which a young woman driven mad by love (apparently modelled by a fellow inmate) stares intently at the viewer from beneath a birds’ nest crown of twigs, flowers, feathers and flyaway hair.

Over the course of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the concept of the artist-visionary was solidified and increasingly cultivated by artists themselves, both within and outside the mainstream. Many Romantic and post-Romantic artists such as Eugène Delacroix and Benjamin Robert Haydon, defining themselves in opposition to the rationality of the European Enlightenment, looked back to the visionary William Blake. At the same time, the elevation of the artist outsider coincided with a dramatic increase in the number of possible places where outsiders might be confined. Between 1800 and 1900, some 120 asylums were founded or enlarged across England and Wales. This was accompanied by an expansion of the medical profession, which in turn triggered a proliferation of new illnesses and diagnostic categories. Both Bethlem and Napsbury exemplified what was known as the ‘moral treatment’ for insanity, predicated on rest, routine and light manual work (including some types of art-making). Napsbury in particular was imagined as a rural retreat, its extensively landscaped setting, which included a cricket ground and several small garden pergolas, allowing patients access to fresh air and exercise. By the final decades of the 19th century, though, a new ‘degenerationist’ theory of madness was in the ascendant. Insanity was increasingly understood not through ideas of inspiration or possession, but as a physical deterioration of the brain: as disease, no more, no less.

When Wain came to the attention of the medical establishment in the 1920s, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. This condition had been discussed in medical circles since the 1890s, but acquired its name (which literally means ‘split mind’) only in 1908. Defined by the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, who was working at the Heidelberg asylum, schizophrenia involved the irreversible breakdown of a patient’s mental faculties. In this sense it was opposed to ‘manic depression’, whose effects were understood to be cyclical. As doctors sought to conceptualise it in subsequent decades, the ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’ became a useful reference point. They offered a window into the mind of the schizophrenic – despite being, at least in one sense, a psychiatrist’s creation. It was Maclay who first grouped them together and it was Maclay who organised them into a numbered, chronological series, writing to a friend that, though they had all been produced by the same hand, they ‘showed such contrasting styles that I feel that some were done before his illness and some afterwards’. In 1950, Francis Reitman, of the Netherne Hospital in Surrey, argued that the ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’ sequence demonstrated the loss of psychic ‘unity’ and organisation characteristic of schizophrenia. Describing how, in patients he had observed, ‘a conceptual deterioration takes place and the organisation of pattern disintegrates’, he contrasted the cats Maclay had put earlier in the sequence (‘well organised as a whole’) with the abstract ones at the end (‘lost in a maze of parts’).

Three Cats and a Plum Pudding (n.d.), Louis Wain. Bethlem Museum of the Mind, London.

Like Maclay, Reitman had spent time at the relentlessly experimental Maudsley Hospital, a psychiatric facility specifically designed for teaching and research which had opened in 1923. The Maudsley actively sought new curative approaches, moving away from ‘moral treatment’ to explore shock therapy, leucotomy and chemical intervention. In the final decade of Wain’s life, Maclay and a colleague, the German emigré Eric Guttmann, were running a series of studies at the Maudsley using the hallucinogenic drug mescaline. It was widely believed that the temporary state of mind triggered by mescaline was comparable to psychosis, and so could allow doctors to experience schizophrenia for themselves – an ‘empathetic’ approach that apparently endured well into the mid century (Reitman recalled ‘ask[ing] people irritably to leave me in peace, so that I could enjoy my hallucinations undisturbed’). However, Guttmann and Maclay were particularly interested in the effects of schizophrenia – and therefore mescaline – on artists. When he found the ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’ Maclay was already seeking out examples of work by artists known or believed to have suffered from mental ill health. His collection included artists as disparate as the Royal Academician-turned-spiritualist Charles Sims and the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, both of whom had breakdowns during the First World War.

For psychiatrists, the luminescent colours, geometric, fractal-like forms and jagged force fields in the ‘final’ images in the ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’ series corresponded, usefully, to the mescaline experience. They therefore confirmed schizophrenia as a state of altered consciousness, and the art produced under its influence as partly the result of a broken and disorganised mind. (A more positive assessment of the ‘trippy’ quality of Wain’s art would later assist his reclamation as a counter-cultural hero by artists and musicians in the second half of the 20th century.) At the same time, Guttmann and Maclay’s experiments coincided with other developments in painting generally, many of which were directly compared (for better or worse) with ‘asylum art’. A selection of Wain’s paintings was exhibited in 1925 in London at Twenty-One Gallery, Adelphi, which also championed the work of William Nicholson, Jacob Epstein and Graham Sutherland; in the following decades, the painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet began assembling his collection of so-called Art Brut – work, as he put it, ‘emanating from obscure personalities, maniacs […] animated by fantasy, even delirium’. This positive strand of re-examination was in part a reaction to events elsewhere. In the 1930s, Nazi exhibitions of ‘degenerate art’ juxtaposed work by contemporary modernists with work from the art collection of the psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn, primarily produced by patients at the Heidelberg asylum. The suggested equivalence between mental and artistic ‘degeneration’ turned on its head the celebratory concept of the artist-visionary. However, it also, conversely, suggested that in the works of some of these patients, there might be more to see.

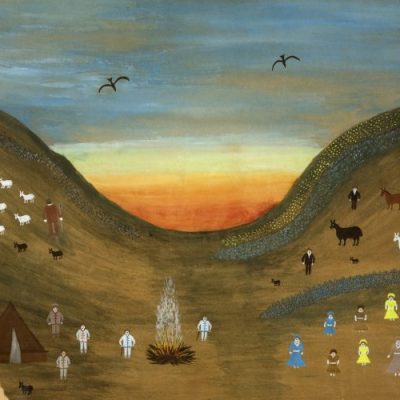

A Cricket Catastrophe (n.d.), Louis Wain. Bethlem Museum of the Mind, London

Far from indicating a loss of his powers, Wain’s ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’ are among his most seductive works. They are intricate, tightly controlled and almost perfectly symmetrical – his biographer, Rodney Dale, points out that Wain was ambidextrous and suggests he may have worked on them with both hands simultaneously. The paintings he produced after 1924 are abstract and figurative in equal measure, neither mode predominating. In many of them, cats ramble in sweeping gardens, in front of fantastical buildings, half thatched and half Italianate, dimly reminiscent of the architecture of Napsbury. Though they do recall the intricate reflections of the kaleidoscope, his densely patterned pieces are also reminiscent of the kind of decorative work produced by his mother – Compton noted that she was responsible for the designs of ‘the finest Turkey carpets’ – or even his sisters, several of whom made ornamental paintings along the edges of book pages and on glass. This is indeed how his sisters seem to have understood them. They continued to visit every week, and to collect any artwork that could be sold, but (according to one of the nurses) they rejected ‘that wallpaper rubbish’, which could not. In the asylum, the unworldly Louis Wain seems to have found comparative freedom from such constraints – able, at last, to experiment and explore.

From the November 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.