From the October 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

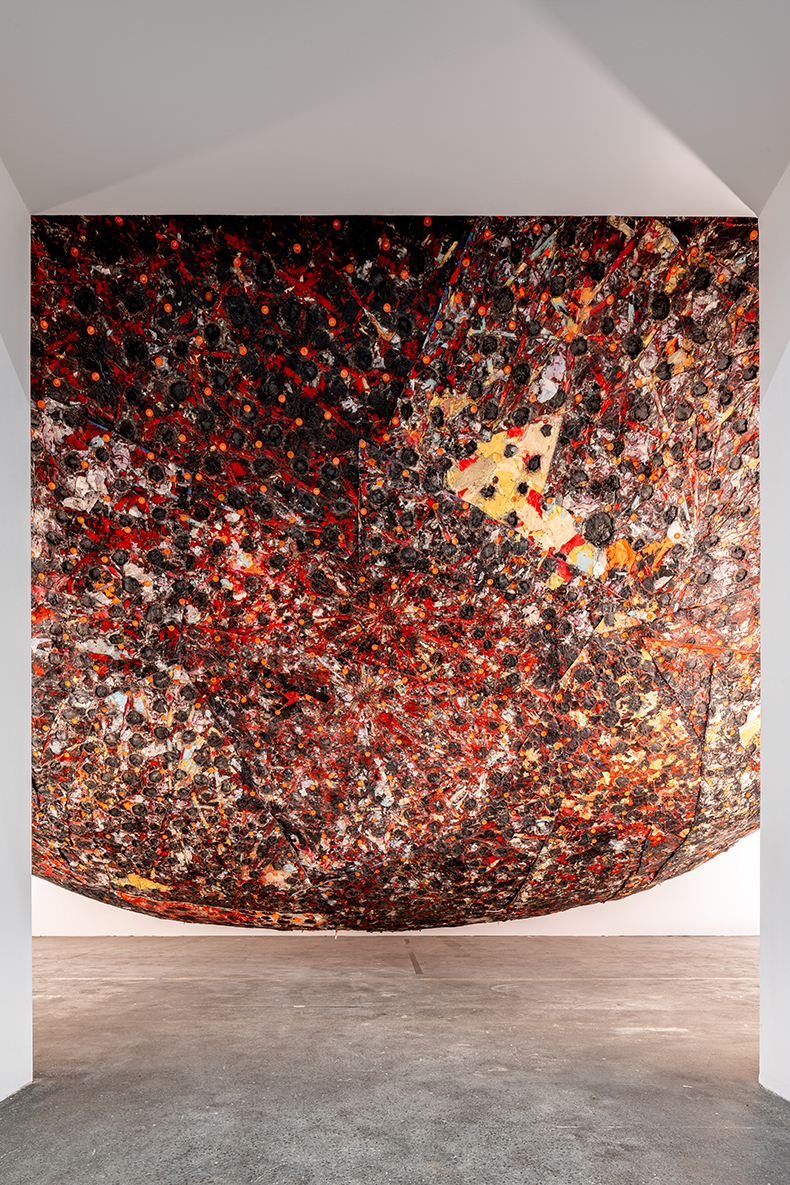

Mark Bradford has a fruitfully impatient relationship to abstract painting; its insularities are not enough for him. The majority of the 20 works (dating from 2005–24) in his first German institutional show are bedecked with paint, many hang on the wall and most recall nonfigurative styles, from Abstract Expressionism to minimalism. In the Los Angeles-born artist’s work, though, such historical aesthetics collide – hard – with the real world. His forms and surfaces often suggest bodies: bruised, damaged, at risk, resilient. Visitors to the 2017 Venice Biennale know this already; the centrepiece of Bradford’s US Pavilion, Spoiled Foot (2016), a ceiling-suspended form covered in mottled, purplish-red paint, swells within an early room here like a colossal tumour. Dating from the year of Trump’s election, it suggests something profoundly wrong and growing in the social sphere, shrinking available space for marginality, and radiating violence; its surface is repeatedly indented, as if punched or kicked.

Another para-painting, Float (2019/24), covers the floor of a later room with rough, thin rows of canvas painted in a muddy rainbow of colours, intermingled with multihued lengths of stretchy, potentially restraining tension straps. The bright surface is uneven, canvas curling up sometimes into looping wavelets; at the show’s opening, moving too fast, I slapstick-tripped and felt bodied like the minimalists wanted. That’s the beginning of Float’s kinaesthetic affect. The corollary, as so often in the work of this Black, queer, pro-basketballer-lanky artist is: what kind of body do you have? What affordances do or don’t come with it, particularly in public space, even risking danger if your body doesn’t fit? What, who, are you stepping heedlessly on? And – the work’s arcing, major-key hope – once made present in our frames, might we become conscious of those of others, the cross-identity communality of inhabiting human bodies?

Installation view of Spoiled Foot (2016) in ‘Mark Bradford. Keep Walking’ at Hamburger Bahnhof, 2024. Photo: Jacopo La Forgia; © Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; courtesy Mark Bradford/Hauser & Wirth; © the artist

The stripes of Float lead towards a video work, Niagara (2005), for which Bradford filmed, from behind, a young Black man in white vest and yellow knee-length shorts who regularly sashayed down the sidewalk outside his studio; the artist, watching, flashed back to Marilyn Monroe’s sexy walk in the thriller Niagara (1953). For a white woman that strut is coded one way; for a Black man another and, in public space, potentially dangerously. Ventriloquise the show’s title, ‘Keep Walking’, in this regard: imagine a police officer saying it to someone who, they reckon, shouldn’t linger in that area; to someone else, it might be an encouragement, as in ‘keep going’. Bridging that disparity, someone might determinedly keep walking in the face of repeatedly being told to ‘keep walking’.

Born in 1961, Bradford reached maturity right as AIDS was beginning to devastate the gay community, a crisis given a twist – often unto painful silence – by intersectionality. Pinocchio is on Fire (2010) consists of a narrowing corridor composed of two converging freestanding walls, recalling a Bruce Nauman installation, insides covered in a graphic pattern of overlapping newspaper sheets that are blacked out, leaving thin white borders, like empty frames for countless portraits. The wall text affirms that this work has its roots in R&B singer Teddy Pendergrass – who died the year it was made – getting caught with a transgender dancer in 1982 and falling into disfavour with the Black community when the news broke, at the same time as hip hop was dethroning R&B’s musical stylistics. The blacked-out newspapers dream, it seems, of a removal of constructed norms around Black masculinity (and salacious stories about transgressions), against a reality of people hiding their difference to get along.

Installation view of I Don’t Know What I Am (2024) and Spoiled Foot (2016) in ‘Mark Bradford. Keep Walking’ at Hamburger Bahnhof, 2024. Photo: Jacopo La Forgia; © Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; courtesy Mark Bradford/Hauser & Wirth; © the artist

This work’s palette, and structure of overlapping grids, finds its formal negative in a roomful of low-slung, variously titled white paintings from 2024, their wonky, toasty brown grids formed using overlapping, burnt-edged ‘end papers’ used to protect hair while it’s being waved. These works, elevating culturally specific discards, smartly converse with both Agnes Martin’s canvases and David Hammons’s work using Black barbershop hair; and, once again, blacken and make worldly the language of transcendental abstraction.

These paintings surround a figurative sculpture, Death Drop (2023), an oversized, all-white representation of Bradford – wearing a beat-up puffa jacket, splayed on the floor with arms out and one knee bent back – that speaks to subjective reception and how community makes and sustains meaning. For ‘Bradford’ might look dead, but if you know the codes of ballroom culture’s Black and queer pageantry, you recognise this as a finale move. At the same time, the work speaks urgently to the vulnerability of the Black queer body and contrasts it with the unconsidered privileges of whiteness. The gallery floor flickers; it’s a ballroom scene, it’s an inner-city pavement, it’s a park after dark. The body strobes between white and Black.

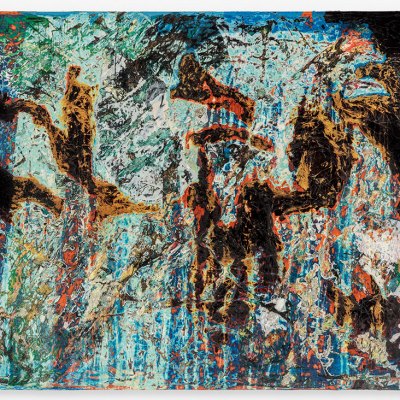

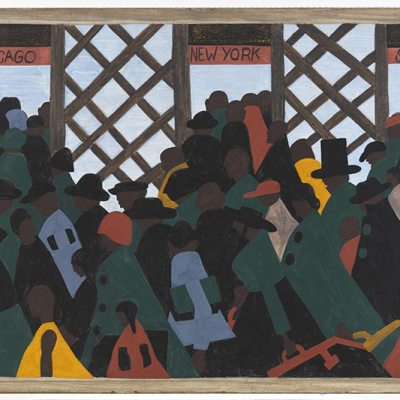

‘Keep Walking’ opens with two big paintings, festooned with rows of raised numbers, that engage with voluntary and involuntary movement (and thus chime somewhat with the various inferences of the title). They reproduce old timetables relating to the Great Migration, when six million Black Americans left the South between 1910 and 1970; swathes of black and greyish paint across them suggest maps and geography.

The Hamburger Bahnhof being a former train station (as many previous exhibiting artists have pointed out) and Nazi deportation centre, such references also do double-duty, grimly summoning another six million bodies. A lazy eye on these paintings recalls mid-century Ab-Ex painter Clyfford Still; to move in, though, is to see other narratives orbiting around that time frame, and enter a world of pain. Those of us still living, Bradford suggests, ought to remember all this and the present-day lives of others, and somehow keep walking. Art may help.

‘Mark Bradford: Keep Walking’ is at the Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, until 18 May 2025.

From the October 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.