Amid the tableau of increasingly anodyne skyscrapers jostling for supremacy in the City of London, Minster Court sticks out gloriously. ‘Monster Court’ or ‘Munster Court’, as it has become known (after the spoof horror series from the 1960s) is a modern Gormenghast or Neuschwanstein. Lavishly adorned with turrets, balconies and mock buttresses in the style of a classic villain’s lair, it served as Cruella de Vil’s headquarters in the 1996 live-action remake of 101 Dalmatians.

Conceived in the late 1980s, when the City was on a high after the Big Bang, the building attracted a mixed critical reception when it was first unveiled. Its architects, Gollins Melvin Ward (GMW) pulled all out the stylistic stops to contrive a corporate Gesamtkunstwerk featuring a 16-storey cat’s cradle of escalators suspended from a rooftop ring beam, and a trio of bronze horses (nicknamed Sterling, Dollar and Yen) by the sculptor Althea Wynne in its central courtyard. Resoundingly of its time, Minster Court is one of the few buildings to translate the frenetic, deal-doing energy of the City into a uniquely expressive kind of architecture. It has since become a cherished landmark within the Square Mile, a camp interloper amid a sea of metaphorical grey suits.

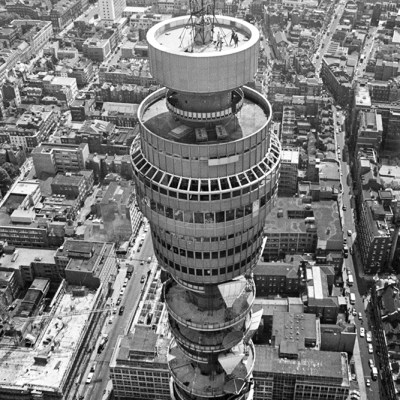

Minster Court as seen from the junction of Mark Lane and Great Tower Street, in the City of London. Photo: View Pictures/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Now comes the dire news that it is due for a makeover – one that stops short of outright demolition but is akin to an architectural lobotomy, aspiring to smooth down its sharp edges and elide precisely the things that give the building its wayward charm. The developer M&G Real Estate seems determined to transform it into a more marketable proposition. The architecture firm Wilkinson Eyre has been hired to add extra floors and generally spruce it up, but after these ministrations, Minster will be more or less unrecognisable, its neo-Bavarian quirks sternly ironed out.

Money talks, of course, and the trick these days is to shoehorn as much lettable floor space as possible into insipid extrusions of capitalism and give them chummy nicknames, such as the Walkie-Talkie and the Scalpel. The impetus to conserve architectural character – regardless of stylistic era – seems to count for very little. It’s a familiar pattern, illustrated not just by the emasculation of Minster Court, but also by more drastic removal tactics. Recently, the death knell was finally sounded for Bastion House, a 17-storey modernist monolith on London Wall; and the neighbouring Museum of London, both designed by Powell & Moya and both fine buildings that epitomise their respective eras. They are due to be replaced by a trio of office buildings designed by DS+R, in a scheme which attracted nearly 1,000 objections at the planning stage. As well as the loss of character, demolition invariably involves the squandering of resources and energy, so it seems reasonable to ask why new uses could not be found for both buildings.

View up from the atrium of 3 Minster Court, showing its many storeys of suspended escalators. Photo: Historic England/Heritage Images via Getty Images

It seems that Minster Court’s villain’s lair vibe was thought to be too disconcerting, so the revamp attempts to address this by the inclusion of a public roof terrace ‘where people can get away from the hustle and bustle of life in the Square Mile’ and a ‘Basement Box’, which will apparently function as a new cultural venue. Consultation documents describe the existing site as having an impervious street level frontage which ‘creates the overall impression of a defensive design which is not inviting or approachable’. But perhaps, that was just the point. The Twentieth Century Society, which has been fighting for Minster Court’s retention through an ultimately unsuccessful listing application, is of the opinion that ‘the Square Mile will be so much the poorer and blander without its theatrical slice of Gotham on the skyline.’

Historically, the City is a broad church, where Wren steeples jostle with High Tech ductwork, but you only have to look dull, clompy horrors (such as the aforementioned Walkie-Talkie and the Scalpel) to intuit the general direction of architectural travel. Generic skyscrapers, the higher the better, have come to dominate the skyline, so all the more reason to preserve and extol more iconoclastic creations. Sadly, however, it looks as though a living death through blandification looms for the Square Mile’s Gormenghast, as it does for many others. Surely these buildings deserve better.

The entrance to Minster Court as viewed from Mincing Lane in the City of London, designed by GMW and opened in 1993. Photo: View Pictures/Universal Images Group via Getty Images