From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Monet is only an eye, but what an eye,’ Cézanne once quipped. Jackie Wullschläger’s new biography aims to resurrect the man behind that organ. That an artist as beloved as Monet should have gone until now without an English-language biography is surprising. It prompts us to ask: does knowing the artist let us see the art more clearly? It’s a particularly vexing question in the case of Monet, whose canvases seem designed to delight the viewer’s eye without taxing her historical knowledge. The artist’s ambition to paint ‘what I myself will have experienced, I alone’ (what Pissarro called Monet’s ‘pure’ painting) also seems to have laid the groundwork for the severance of eye from body, canvas from life. Monet’s experience is painted everywhere into his canvases, and yet those scenes – women reading, children lolling, men loitering – seem so homely, so familiar, so easy, that we can forget that they emerged from one man’s life.

It’s a life worthy of the telling. Monet was the quiet centre of a world of bigwigs and upstarts, one which Wullschläger reconstructs from the artist’s copious (and hitherto untranslated) correspondence. John Singer Sargent and Henri Matisse made pilgrimages to his garden at Giverny; Prince Eugen of Sweden paid homage in Oslo; Winnaretta Singer, the American princesse de Polignac, welcomed the artist to her Paris salon. And though Monet kept far from politics, it was his best friend Georges Clemenceau, the former French prime minister, who collapsed, sobbing, at the artist’s funeral in 1926.

Can we see Monet’s paintings differently for knowing the man? Sometimes. Take Impression, Sunrise (1872). That beloved red sunrise over the bluescale harbour at Le Havre could be taken as Whistlerian meditation, a painting designed to appeal to – and wholly satisfy – our eye’s appetite. Licks of peach toss the rising sun’s rays above the teal crests of a placid mauve. When Louis Leroy wrote of the painting that ‘[w]allpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape!’, he rehearsed the popular opinion that the Impressionist canvas, because of its uninhibited (and undisguised) facture, was a cheap gimmick. But what critics first deemed a ‘war on beauty’ turned out to be lucrative.

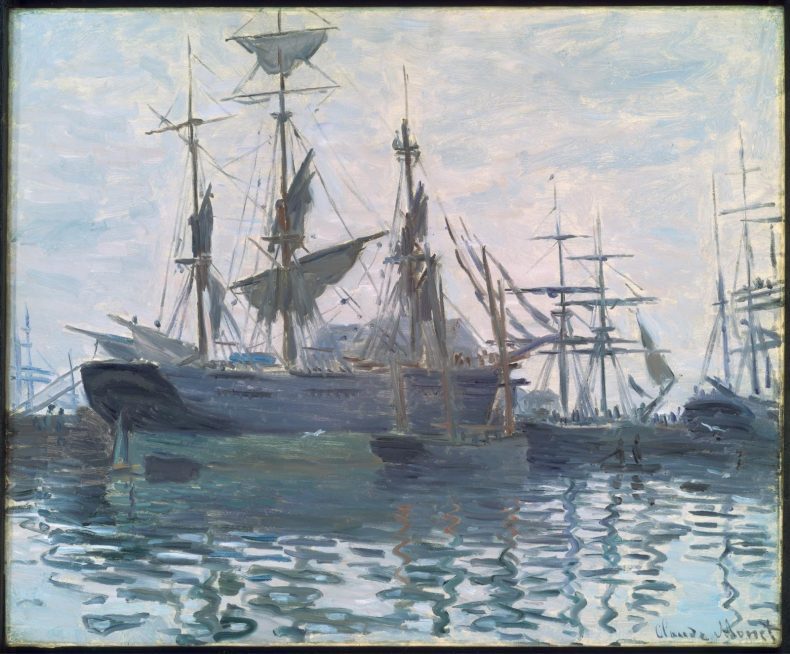

Ships in a Harbour (1873), Claude Monet. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

That is Impressionism’s heroic tale: the triumph of a daring eye over a staid artistic scene and a prudish public. Wullschläger tells us to look again. She finds capital and industry in the crumpled cranes and lilac plumes of the painting that gave Impressionism its name. Le Havre, when Monet grew up there, was far from a sleepy seaside town. It was, one critic marvelled, the ‘warehouse of the whole world’. Its dug-out basins welcomed the largest transatlantic steamers, which spewed their dirty smoke into Monet’s view. It was here that Pissarro first arrived from the Caribbean; that Monet set off for military service in colonial Algeria; from here that both fled to London in 1870. Though Monet maintained that his practice was circumscribed by personal experience, we learn that his paintings were embedded in these international trajectories.

Le Havre was also decisive in shaping Monet as a painter of water. Zola joked that ‘Monet loves water as one loves a sweetheart’; the artist himself employed a different epithet: ‘the slut!’ The dealer Paul Durand-Ruel bragged he could ‘mint money’ with Monet’s seascapes. From Le Havre’s industrial horizons to Vétheuil’s ice floes, from Norwegian fjords to Venetian canals, Monet remained close to water all his life. A houseboat that ran up and down the Seine let him paint en plein eau, sometimes literally: the artist reported, to the great alarm of his second wife, Alice, that a wave had claimed his canvas, his paint and nearly his life.

To break the myth of the great male artist – or maybe, to just crack it – is one of this biography’s ambitions. Three women enabled Monet’s ‘restless’ vision, and here they are given their due, even if Wullschläger’s insistence on their equal partnership in Monet’s career occasionally rings hollow. Camille Doncieux was the partner of his youth, the keeper of drained accounts and ‘colluder’ in early bids for Salon admission. It’s her coy pout that earned him a spot for Camille (1866), but her poses kept pace with his changing style and nine years later she traipses through Monet’s most recognisable canvases, parasol in hand, spinning the sky around their young son.

Camille (1866), Claude Monet. Kunsthalle Bremen

When she fell ill shortly thereafter, Monet’s second wife entered the scene. Alice Hoschedé, a socialite and then-wife of Monet’s most ardent supporter, was a tender nurse to the dying Camille and, subsequently, mother to Monet’s motherless boys. Her legendary hospitality lured collectors who bought Monet’s work – and drove up his prices. After Alice’s death in 1911 (‘I am lost,’ Monet despaired), her daughter Blanche, a painter herself, went from the artist’s devoted disciple to his indispensable caretaker. She hauled canvases, puffed parasols and protected the ailing painter from the prying eyes of journalists. When Monet began to lose his sight and destroyed his paintings in fits of frustrated rage, it was Blanche who saved some – and helped him to slash others.

Water Lilies (1906), Claude Monet. Art Institute of Chicago

In these final years, Monet quoted Cézanne’s witticism back to the critic Gustave Geffroy: ‘They say of me, Claude Monet is only an eye, but what an eye. It’s no longer worth much now, that eye.’ A photograph that closes this new biography captures the artist’s ambivalence. Painting in Giverny one afternoon, Monet swapped his brushes for a camera. He leaned over the pond’s edge, a Narcissus for the new century. On brown water choked with the flat discs of waterlilies, his shadow flickered. Wide face, sloping shoulders, that tell-tale Panama hat: a signature in silhouette. He snapped the shutter. ‘Monet was here,’ the image seems to say. Or maybe not. His likeness lingers on the margins of a view he painted hundreds of times, still not sure that it belongs.

Monet: The Restless Vision by Jackie Wullschläger is published by Allen Lane.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)