On the quincentenary of his death, few, if any, of Hieronymus Bosch’s contemporaries can claim a similar level of continuing fame. He is a major draw at museums, but his reach extends far beyond: in addition to the standard books, T-shirts and postcards, he has been treated to accessories ranging from tote bags to mousepads and phone cases. There are even Dr. Martens boots with his work printed on them.

But being widely known is not the same as being well known. The image of Bosch that still exerts such a strong grip on the popular imagination is that of a prototype outsider artist. And the way ‘Boschian’ is used – nightmarish, monstrous, teemingly weird – perfectly fits the image of a marginal figure, at odds with the artistic norms of his time. The kind of figure, in short, that Dr. Martens, keen to prop up their own countercultural cred, would want on their boots.

Bosch scholars, however, would leap to correct this. For all the singularity of his work, there is no evidence to suggest that Bosch was, in any sense, an outsider. While some generously speculative research in the 1940s attempted to link him to an heretical sex cult called the Adamites, and while the 1960s zeitgeist had him hallucinating on ergotic wheat, mainstream academic opinion offers a much tamer picture. Born Jheronimus van Aken around 1450 in ‘s-Hertogenbosch (or Den Bosch, from which he adopted his name), nothing suggests that Bosch was anything other than a prominent, prosperous citizen, an orthodox Catholic, and a devotional painter much in demand among patrons.

Christ Carrying the Cross, c. 1510–35, follower of Hieronymus Bosch (formerly attrib. to Hieronymus Bosch). Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent

There is something important, though, about the gap between what life records and what historical evidence tell us about Bosch himself – and what we mean when we say ‘Boschian’. The moment that a term like Kafkaesque or Rubenesque, Dickensian or Boschian becomes a term, it tends to escape the orbit of the works that birthed it; and in the process it risks eclipsing those works. The more complete the eclipse, the more urgent it becomes to ask what the works behind the adjective are really like: to see how they measure up to and differ from the idea. While calls for reassessment are normally the province of artists fallen into obscurity, they can be equally urgent in cases where, as with Bosch, fame itself helps obscure the work.

In Bosch’s case – with the 45 paintings and drawings currently attributed to him spread across 10 countries, 18 cities, and 20 collections in Europe and North America – few people have had the chance to measure the myth against reality by looking at many of the works themselves. Happily, the quincentenary of his death offers two chances to do exactly that, with major shows at the Prado (31 May–11 September) and the Het Noordbrabants Museum in Den Bosch (until 8 May). While the Prado show will set a selection of Bosch’s work against paintings by contemporaries and successors, the Noordbrabants Museum’s ‘Jheronimus Bosch: Visions of Genius’ brings together an astonishing 20 of the 25 surviving Bosch panels, and 19 of his 25 surviving drawings for as close to a complete overview of Bosch as one will ever see. It is both a lavish tribute to the town’s most famous son, and a show that promises to shed new light on his work. In a new paradigm for inter-gallery loans, the museum’s director, Charles De Mooij, persuaded institutions like the Louvre and the Prado to lend some of their most high-profile pieces in exchange for research gathered over five years, carried out by the Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP). For their generosity, the participating museums are learning more about their works – with the results assembled for public consumption in a two-volume monograph released to accompany the show.

Infernal Landscape, c. 1500, Hieronymus Bosch (formerly attrib. to a follower of Bosch). Photo: Rik Klein Gotink and Robert G. Erdmann for the Bosch Research and Conservation Project

The BRCP has announced several important discoveries, not least the reattribution to Bosch of a little-known painting, The Temptation of St Anthony (c. 1500–10) from the Nelson-Atkins Museum. Among other findings is confirmation of some scholars’ suspicions that Christ Carrying the Cross, at the Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Ghent, is not a Bosch original, while a drawing formerly attributed to a workshop pupil appears to be the master’s own. While the canon is hardly being turned inside out, findings like this are instructive. The case of Ghent Museum’s Christ Carrying the Cross, for instance, helps dispel any notion that Bosch is primarily a grotesque painter. The Ghent painting’s distorted faces are precisely that, every one leering or snarling with glee as they harry Christ to his fate: it is simplistic, Manichean physiognomy in action. Bosch’s treatments of the same subject are, by comparison, distinctly un-grotesque. In the Palacio Real’s Christ Carrying the Cross (c. 1495–1505), the faces of those around Christ depict a more morally complex universe. Where the soldiers in the Ghent painting relish their task, Bosch’s wears the tired, resigned face of a man bored of his job. With his vague five o’clock shadow and slightly pursed lips caught mid-sigh, he resembles nothing so much as a conscript near the end of guard duty.

A major difference between these two paintings is compositional. It is hard, if not invidious, to compare the aggressively planar make-up of the Ghent painting with the deep landscape of the Palacio Real’s. They are after different kinds of perspective, spiritual as well as literal, on Christ’s suffering. A fairer comparison for the claustrophobia of the Ghent Christ is with the National Gallery’s Christ Mocked (c. 1510), where it becomes clear how differently Bosch handles planar space. Like the Ghent picture, Christ Mocked puts the Messiah at the centre of a crowd of faces, but unlike the Ghent picture, Bosch’s Christ is both crowded and spacious. Even as they crowd in on Christ, each face is given room; and the viewer can take each one in, and has to. Where Ghent grotesques express little beyond their own grotesqueness, the figures in Bosch’s Christ express individually and are subtly characterised. Looking at the figure in the top right, leaning in towards Christ, one sees the expression, at once interrogatory and conspiratorial, of the ‘good cop’ in the interview room: the quizzical frown of a man trying, or pretending to try, to empathise with someone entirely in his power. And the insidious threat of that power dynamic pours out through the firm hand on Christ’s shoulder: both a false reassurance and reminder of who is in charge. In the context of the Ghent Christ’s overdone Boschianism, the National Gallery and Palacio Real paintings reveal Bosch not so much as a grotesque painter, but as a master of human expression in the vein of predecessors like Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck.

Comparisons of this sort are infamously slippery. Whatever they can show about Bosch’s particular talents, confirmation bias is such that it’s almost impossible not to favour him in the comparison. And of course, there is always the risk of being contradicted by evidence from techniques like X-ray crystallography, infrared imaging, and dendrochronology – methods that carry their own interpretative pitfalls, but can nonetheless be hard to dismiss with a wave of the connoisseurial hand. As Stefan Fischer notes in Taschen’s sumptuous Hieronymus Bosch: Complete Works (another happy by-product of Bosch’s quincentenary), Christ Mocked has more than once been rejected from the Bosch canon for not being grotesque enough, while the hell scene newly restored to Bosch by the BRCP once seemed too Boschian to be true. In almost any other artist, this instability would be called ‘range’ – something that Bosch, for all the praise of his visionary oddness, has rarely been credited with in the popular imagination. He is as capable of being subtle as he is grotesque.

There is, however, another side to the process of digging down to the ‘real’ Bosch. The efforts to return Bosch to his world – to place him back in the religious mainstream of his time, return him to his role as upright citizen of Den Bosch, and trace the origins of even his wildest images – can deny the reality of the popular Bosch: the visionary on the margins. Artists and their canons are symbiotic entities: they are each the means by which we construct the other. And in extreme cases, canon and artist become mutually dependent chimeras, each continuously being constructed and reconstructed with parts taken from the other.

It is hard to think of a more Boschian process, and the chimerical visionary ‘Bosch’ constructed by generations of viewers has its own history and reality. When Bosch died in 1516 he was already one of the best-known painters of his time; he soon became one of the most copied and imitated. By the 1530s, as Walter Gibson notes, there had emerged an entire school of painters in Antwerp dedicated to exactly that – it is with them that Bosch’s visionary image began to crystalise. What modern marketing professionals would call Bosch’s ‘brand recognition’ boiled down to his being seen as a purveyor of hellish diableries. The imitators and copyists’ Bosch was not the man behind the stilly contemplative Adoration of the Magi (1494), but the one behind the taunting devils in the Temptation of St Anthony (c. 1500). Focused on what was most marketable, they helped fix the image that persists today.

Then as now, scholars were keen to counter the simplification and flattening of Bosch’s image. The Spanish humanist Felipe de Guevara, attempting to correct the ‘vulgar error’ in his Comentarios de la pintura (c. 1560), launched a valiant defence of the real Bosch, pointing out he was far from being merely an ‘inventor of monsters and chimeras’. The imitators were mistaken in believing that ‘painting monsters and wild imaginings’ was all it took to imitate him. The image stuck, though, and imitations of the chimerical Bosch flooded the market. By de Guevara’s testimony, they were to be found in ‘infinite’ numbers, many falsely signed with Bosch’s name, and even, he noted, smoked in chimneys to give a patina of age and authority. Today, at a rough count, the surviving Bosch oeuvre is still outnumbered by copies at a ratio of between 10 and 15 to one – ranging from careful reproductions of his most famous paintings, to rough-and-ready approximations drawing freely on the motifs and types of scene associated with him.

The copyists and imitators had a hugely reinforcing effect on the image of Bosch as a cracked visionary. By the early 1570s, the real artist had faded far enough into the background for the chimerical ‘Hieronymus Bosch’ to become an object of awed fascination. In Dominicus Lampsonius’s Effigies (1572), the portrait of Bosch is the subject of fearful enquiry:

What does that astonished eye of yours mean,

Hieronymus Bosch? What does your face’s pallor mean?

As if you had observed, with your own eyes, evil ghosts,

Spectres from Erebus flying around?

That Bosch could not respond except through a canon increasingly tilted towards his wildest ‘imaginings’, reinforced by those of his imitators, only entrenched the image of him as a wild-eyed witness to the horrors of hell.

The Bosch vogue was by no means all bad. Even de Guevara admitted that the imitations could (occasionally) surpass the originals. He ascribed the Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (c. 1505–10) to a pupil who was, to his eye, even ‘more diligent and patient’ than his master – an attribution, if not a judgement, recently confirmed by the BCRP. Though that artist’s name is unknown, one imitator has lived on as a master in his own right: Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Though he is better known for his scenes of everyday peasant life, his training in Antwerp (entering into the painters guild there in 1551) put him at the centre of the Bosch industry, where he flourished. The association between Bruegel’s work and Bosch’s was so close that in Lampsonius’s Effigies, he is the ‘new Bosch’, emulating his ‘master’s ingenious dreams’, while another contemporary records him going by the nickname ‘Second Hieronymus’.

Big Fish Eat Little Fish, 1557, engraved by Pieter van der Heyden after a drawing by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

That emulative relationship is clearest in the works that Bruegel produced for the printer Hieronymus Cock in the late 1550s. Cock was no stranger to the money-making opportunities for Boschian work: he put out 46 pseudo-Bosch prints, and around a third of his 64 Bruegel prints treat recognisably Boschian subjects. The prints are a fertile source of exactly the kinds of ‘wild imaginings’ that Guevara bemoaned, and an object lesson in the flexibility of attribution. Big Fish Eat Little Fish, can confidently be ascribed to Bruegel on the basis of the original drawing signed by him (held at the Albertina), but nevertheless it bears the legend ‘Hieronymus Bos. inventor’. The false attribution makes sense: much of what is inventive here can be traced back to Bosch. The giant knife slicing open the belly of the central fish is to be found in the central panel of his Last Judgement and twice in the right-hand panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights; the flying fish has swooped in from the skies of the Temptation of St Anthony; the fish waddling off on human legs, from the central panel of the Last Judgement.

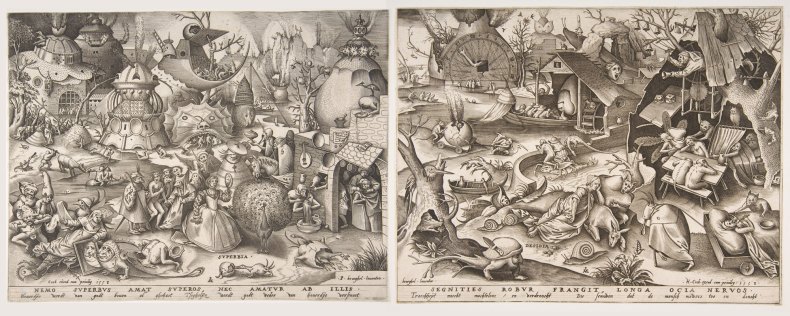

Superbia (Pride) and Desidia (Sloth), from the Seven Deadly Sins series (1558), engraved by Pieter van der Heyden after a drawing by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

If anything, though, Big Fish Eat Little Fish is less ‘Boschian’ than some of the prints put out under Bruegel’s own name. The Seven Deadly Sins series, printed in 1558, out-Bosch Bosch in a triumphantly busy agglomeration of everything associated with his most famous work. Superbia (Pride) combines the Temptation of St Anthony’s characteristically squat, good-humoured monsters and the semi-organic architectural forms of the Garden of Earthly Delights. In Desidia (Sloth), the house-sized figure squatting in the central structure reprises the pose and scale of the famous ‘Tree-Man’, in the Garden’s hell panel (seen here in a preparatory sketch once falsely attributed to Bruegel himself). The series as a whole is a Bosch greatest hits, except by Bruegel. Looked at like this, the inscription ‘Bruegel inventor’ in the bottom left-hand corner of the Sins prints seems almost less fitting than the false ‘Bos. inventor’ of Big Fish Eat Little Fish. Which is a Bruegel invented by Bosch, and which is a Bosch invented by Bruegel is not an easy question to settle.

Tree-Man, c. 1505, Hieronymus Bosch (formerly attrib. to Pieter Bruegel the Elder). Albertina, Vienna

Nor is the question of where the real Bosch lies in all of this. Breugel and Lampsonius’s wild-eyed visionary looking into hell might be a chimera, but he is in his way just as real as the modern scholars’ good Catholic and middle-class citizen. Inevitably, both will be present at ‘Visions of Genius’. And while viewers should be careful not to look at the paintings too much through Bruegel and Lampsonius’s eyes, Bosch’s own fame is a reminder of how appealing chimeras can be.

‘Jheronimus Bosch: Visions of Genius’ is at the Den Bosch Het Noordbrabants Museum until 8 May.

From the March issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.