‘In his bold flights of irregular fancy, his powerful mind rises superior to common conceptions, and entitles him to the high distinctive appellation of the Shakespeare of Architects.’ Such was the opinion of John Soane of the works of Sir John Vanbrugh. This was praise indeed, for – as the current exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum (on ‘Shakespeare in Soane’s Architectural Imagination’; until 8 October) makes clear – he was very fond of the theatre and involved in the growing cult of Shakespeare. A bust of the Bard was installed in a special niche on the staircase in the house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields; he owned a First Folio; and he quoted ad nauseam in his Royal Academy lectures the lines from The Tempest that could be related to architecture: ‘The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, / The solemn temples…’

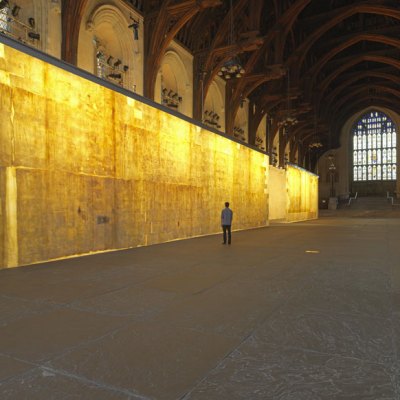

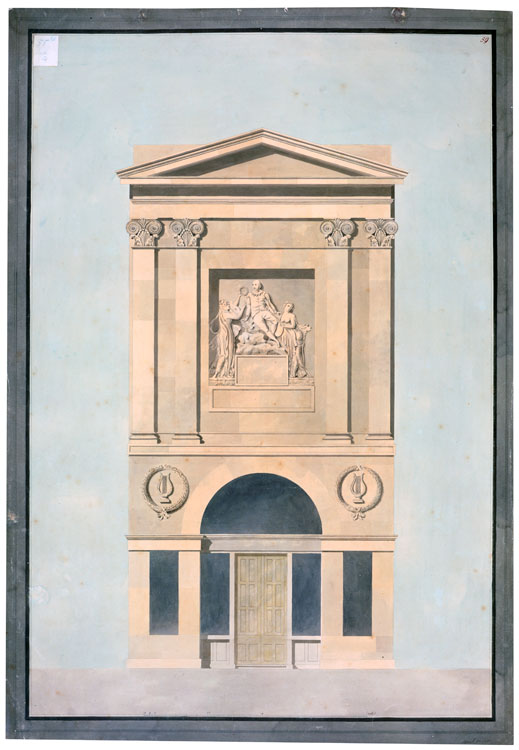

Soane’s praise of Vanbrugh’s architecture is refreshing as it denies what has become the conventional association – dismally represented by Stratford-upon-Avon – between the world of Shakespeare and half-timbered neo-Tudor architecture. Similarly, David Garrick, the great actor in whom Soane was also interested and who organised the first Shakespeare Jubilee at Stratford in 1769, could erect the Ionic domed Temple to Shakespeare by the Thames close to his house at Hampton. And then there was the intriguing Shakespeare Gallery created in Pall Mall in 1788–89 by the print-seller John Boydell. This, the second purpose-built art gallery in England, was designed by Soane’s former master, the younger George Dance, who gave it a classical façade with pilasters sporting his invented ammonite order. But what was important was the interior of top-lit gallery spaces, connected by arches, which influenced Soane’s design for the Dulwich Picture Gallery.

The façade of John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery on Pall Mall, built in 1788–89 and shown here in a Royal Academy lecture drawing by the Soane office of c. 1806–15. Courtesy Sir John Soane’s Museum

By the time of Soane’s death, however, Shakespeare was beginning to be understood in terms of the architecture of his day. This was a product of the growing nostalgia for Merrie England and the ‘Olden Time’, the time of the Tudors. It went with a delight in the picturesque, in the rustic cottage orné, giving rise to such things as the thatched cottages at Blaise Hamlet by Soane’s rival John Nash, which had the ‘kind of chimney stacks’, George Repton reported, ‘frequently seen in old cottages and generally in old Manor Houses and buildings of the reign of Queen Elizabeth…’ A century later, in 1924, Ivor Stewart-Liberty could defend the design of the new half-timbered Liberty’s ‘Tudor Shop’ off Regent Street, made from old wooden ships (and bearing the coats of arms of Shakespeare and contemporary poets), by arguing that ‘The Tudor period is the most genuinely English period of domestic architecture.’

Such was the impetus behind modern English domestic architecture for over two centuries. It went with pride in the achievements of the reign of the Virgin Queen, when England was becoming a seafaring world power and was, crucially, Protestant. And the national poet could not escape being associated with what was, for better or for worse, the dominant neo-vernacular style of the time, represented at best by the work of, say, Lutyens and Voysey and, after them, less happily, by many suburban housing estates. With some of these, as Osbert Lancaster put it in 1938 with pardonable exaggeration, ‘the passer-by is a little unnerved at being suddenly confronted with a hundred and fifty accurate reproductions of Anne Hathaway’s cottage, each complete with central heating and garage…’ At least Mrs Shakespeare’s original house at Stratford was real. The problem was that New Place, the house which the poet had bought in his native town had been demolished in the 18th century. There was only the cottage, owned by Shakespeare’s father, in which he may or may not have been born. This humble timber-framed terraced house was bought for the nation in 1847 and stands today, misleadingly cleared of its context and ruthlessly restored, as the ludicrous, hallowed Birthplace.

Mercifully, the task of building a proper Shakespearean theatre in Stratford was taken rather more seriously. A Shakespeare Memorial Association was founded in 1875 and soon was able to build on a site by the river Avon donated by the local brewer, C.E. Flower. Designed by Dodgshun & Unsworth, the theatre opened in 1879 and was not sentimentally Tudor in style. Built of red brick and with a tall tower, it was rather in the robust French military gothic manner associated with William Burges. Unfortunately, it was largely destroyed by fire in 1926 and a competition was then held for a new Shakespeare Memorial Theatre. The result was remarkable on two counts: first, because it was designed by a woman, Elisabeth Scott; second because the building was not, like Liberty’s and countless new houses, neo-Tudor, but a conspicuously modern design, influenced by Dutch and German Expressionism. This may not have been what England and Stratford wanted. The architect Maxwell Fry wrote that ‘No doubt timber-framing was expected, and the new brick was very red.’ Sir Edward Elgar, refused to go inside as it was ‘so unspeakably ugly and wrong’.

The first Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, opened in 1879 and largely destroyed by fire in 1926 (photo: c. 1900). Courtesy the Royal Shakespeare Company

Elisabeth Scott’s theatre had its problems, but the best elements have been retained in the present theatre rebuilt by Bennetts Associates in 2006–10, which incorporates the surviving part of the Victorian building as the Swan Theatre. But what Stratford really wanted – and probably still does – is suggested by the exhibition held in London at Earl’s Court in 1912 on ‘Shakespeare’s England’. The organiser was Mrs George Cornwallis-West, Winston Churchill’s mother; the architect was Edwin Lutyens, who confessed that ‘I feel rather sorry I have anything to do with it…’ It contained replicas of such familiar Merrie England icons as Ford’s Hospital at Coventry as well as the stern of Francis Drake’s flagship, the Revenge. But most of it consisted of half-timbered picturesque streets, one – significantly – leading to a replica of the long-lost Globe Theatre in which Shakespeare’s plays were originally performed.

‘Street leading to the Globe Theatre’ at the ‘Shakespeare’s England’ exhibition at Earl’s Court, London, in 1912. Courtesy the author

The purpose of the event was to raise funds for the establishment of a permanently endowed repertory theatre and the creation of a ‘living and worthy memorial to William Shakespeare’ in time for the tercentenary of his death in 1916. Unfortunately, England had other things on her mind by that point, but the idea of recreating the Globe Theatre was not forgotten and received a boost during another world war when, in 1944, Laurence Olivier began his film of Henry V by panning over a model of Elizabethan London and then focusing on a reconstruction of the celebrated polygonal theatre. This was surely the inspiration behind Sam Wanamaker and Theo Crosby’s project to rebuild the Globe on the banks of the Thames. The result, authentically constructed, which opened in 1997, might be regarded as a neo-Tudor fantasy, the ultimate in nostalgia, but it is based on scholarly research – and it works. It really is serious Shakespearean architecture.

‘The Cloud-Capped Towers’: Shakespeare in Soane’s Architectural Imagination’ is at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, until 8 October 2016.

From the July/August issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.