There is a sense of mystery about On Kawara (1932–2014). Rarely interviewed and almost never photographed, he has remained such an enigma that his art seems almost like a series of perplexing clues to his identity. Best known for his Date Paintings – monochrome canvases depicting nothing but the date upon which each of the nearly 3,000 paintings in the series were completed – Kawara was one of art’s great archivists, meticulously gathering the data of existence itself in works that are part personal history, part meditation on mortality, experience and the passage of time. Marking a decade since his death – at the age of 29,771 days, to use his preferred way of measuring time – exhibitions of Kawara’s work at David Zwirner in London and Paris offer a timely opportunity to consider his legacy.

Born in the town of Kariya in central Japan, Kawara moved to Tokyo in 1951 and quickly fell in with the city’s post-war avant-garde, abandoning the dominant socialist realism of the period for a more surreal, unsettled style that addressed the collective trauma of Japan in the 1950s (he was 12 when the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki). But he soon distanced himself from his earlier work, keeping fewer than 10 paintings from this period, including the four intriguing canvases now on display in Paris – kaleidoscopic compositions of competing forms and patterns, exploding in a manner faintly reminiscent of Vorticism.

Installation view of ‘On Kawara: Early Works’ at David Zwirner, Paris, in 2024. Courtesy One Million Years Foundation and David Zwirner; © One Million Years Foundation

The scenes are claustrophobic, like structures pictured mid-collapse. Golden Home (1956) depicts a tight room with a fragile, honey-coloured stool and table. An upturned bucket spills a mass of leech-like forms that writhe over the vibrant wallpaper and slanting floor. Worms and insects are a recurring motif: in Flood (1955), painted in response to the devastating Kyushu flood of 1953, a horde of ants march into the picture’s dark green vortex of splintering roof tiles; in Untitled (1956), worms escape across a pristine tablecloth, their dark annuli at odds with the immaculate white fabric. There is a sense of rot, decay and infestation in these paintings, like buildings subject to subsidence; the canvases themselves are irregularly shaped, as if to emphasise a society cracked out of alignment. Absentees (1965) presents a scene of incarceration, walls warping impossibly, the outstretched grey fists of the prisoners extending from their blood-red sleeves in anger or desperation. Though Kawara was always reluctant to articulate any social or political commentary underpinning his work, the distress, grief and frustration of a country regaining its footing in the postwar period is palpable.

Kawara left Japan in 1959, following his father to Mexico City before settling permanently in New York in 1964, just as the heroic era of Abstract Expressionism was rounding to a close. On 4 January 1966, he produced his first Date Painting, inaugurating the Today series, a project that would come to occupy a central position in his work for almost half a century. Kawara estimated that he had spent four years of his life on the series, demonstrating a Zen-like dedication to his practice that seems scarcely matched.

Untitled (1956), On Kawara. Courtesy One Million Years Foundation and David Zwirner; © One Million Years Foundation

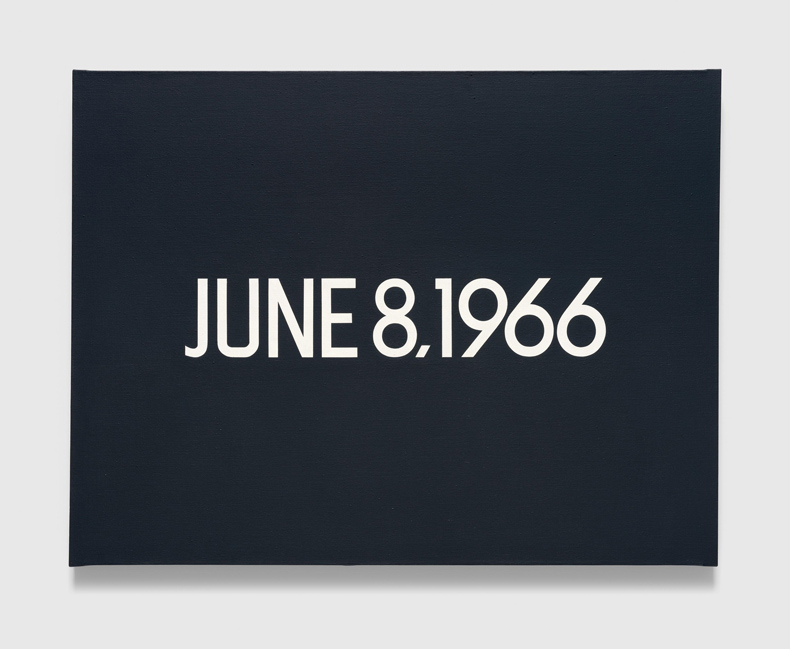

On display in London are 24 Date Paintings, ranging from 1966 to 2012. Gone are the colliding forms of the earlier pictures, their insects and irregularity replaced by right-angled corners and monochrome. Despite the concurrent nature of these exhibitions – scheduled to end on the same date, a neat gag that Kawara might have appreciated – the overwhelming sense is of encountering two separate painters. It is hard to reconcile the seriality and monotony of the Date Paintings with the more vividly expressive work that came before.

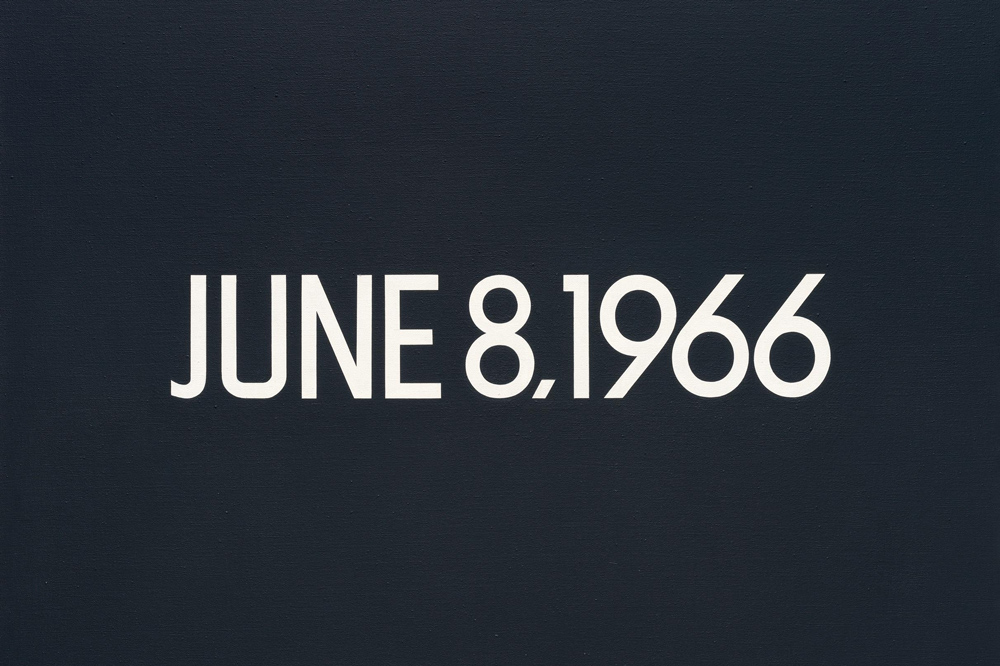

From a purely technical point of view, there seems little to distinguish a Date Painting from the 1980s, say, from one completed in the mid 2000s, an observation that suggests something of the uncanny, time-distorting power of these works. There are various constraints baked into their production. Each adheres to one of eight standard sizes: the smallest measure 8 by 10 inches, the largest 61 by 89. Kawara’s methodology remained resolutely consistent: he would mix the colour of his monochrome ground – grey or blue, occasionally orange – and apply four even layers before carefully drawing the outlines of the date using a ruler and set square, painstakingly painting the white numbers and letters by hand, allowing time for minuscule adjustments and corrections. The dates themselves are represented in the standard form and language of the country that a given painting was completed in. (For countries that do not use the Roman alphabet, Kawara favoured Esperanto.) Most strikingly of all, if a painting remained unfinished by midnight of the day in question, the canvas was destroyed.

JUNE 8, 1966 (1966), from the Today series (1966–2013) by On Kawara. Courtesy One Million Years Foundation and David Zwirner; © One Million Years Foundation

It is tempting to identify a key or pattern in this series, to hunt for significant dates to make sense of their randomness. Often, Kawara would include a snippet from the day’s newspaper in the boxes he created to store every painting; of the sample on display in London, several subheadings refer us to the activities of NASA in the 1960s, at the height of the Space Race. Nevertheless, no obvious sequence emerges. Partly inspired by a pilgrimage to see the cave paintings at Altamira in Spain, the Date Paintings instead offer an assertion of the artist’s existence. They seem related to Kawara’s telegram series (1969–2000), for which he sent close to a thousand messages to friends and acquaintances, each bearing the same brief message: ‘I am still alive.’

The London exhibition includes a wall of 10 paintings, one for each year of the 1970s, hanging in chronological order. Against the stark white of the gallery, they seem like waymarks or headstones, emphasising the linearity – even the unstoppability – of history. At the same time, they resemble the blips of a life-support machine or heart monitor, proof that Kawara, on the dates in question, happened. The paintings speak to our lives, too, forcing us to face mortality – a gentle reminder that our time is limited.

At first glance, Kawara’s paintings seem mechanically produced. Look more closely, however, and subtle differences rise to the surface, revealing the unique fingerprint of every canvas, whether minor variations in the shades of navy and slate-grey, the pencil markings peeking through the dates, or tiny bumps and stray hairs – from a paintbrush or an eyelash – embedded in the picture’s surface. This human presence lies at the heart of the series, raising questions about the purpose and personal value of art making and the traces that we leave behind. Almost by definition, exhibitions of the Date Paintings are always representative. One wonders what it would be like to witness their totality, to be confronted by the full physical scope of Kawara’s project.

Installation view of ‘On Kawara: Date Paintings’ at David Zwirner, London, in 2024. Courtesy One Million Years Foundation and David Zwirner; © One Million Years Foundation

‘On Kawara: Date Paintings’ is at David Zwirner, London, until 25 January 2025.

‘On Kawara: Early Works’ is at David Zwirner, Paris, until 25 January 2025.