From the February 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line, it might represent a Minotaur,’ Picasso said. In Bacchic Scene with Minotaur from Picasso’s Vollard Suite (1930–37), the statement could come straight out of the bull’s mouth. In this drawing, the Minotaur raises a wine glass, as though toasting this realisation, with an ebullient Dionysus sprawled out, flanked and cushioned by two voluptuous, luxuriating women. The composition, like the thought, is evanescent and breezy, directed through a series of thin lines, curved and curlicued, like the bellies, thighs, and breasts it depicts. The figures are outlines, without shading, except for the hirsute faces, chests and genitalia.

Picasso made more than 2,400 prints. A survey of these forms, ranging from etchings to lithographs and linocuts to drypoint, is currently on display in the British Museum’s ‘Picasso: printmaker’ exhibition (until 30 March). Subjects range from classical art history and autobiographical references to mundane objects such as chickens, children, fruit, and crockery. Wine bottles and glasses recur as symbols of the quotidian and perceptual exercises for the artist, especially in cubist still lifes. Alcohol is an important part of his output, from his early years in Paris to his old age in the south of France. In his prints, the marriage of rigid technique with flourishes of expression and interpretation echoes that of winemaking (and drinking) itself.

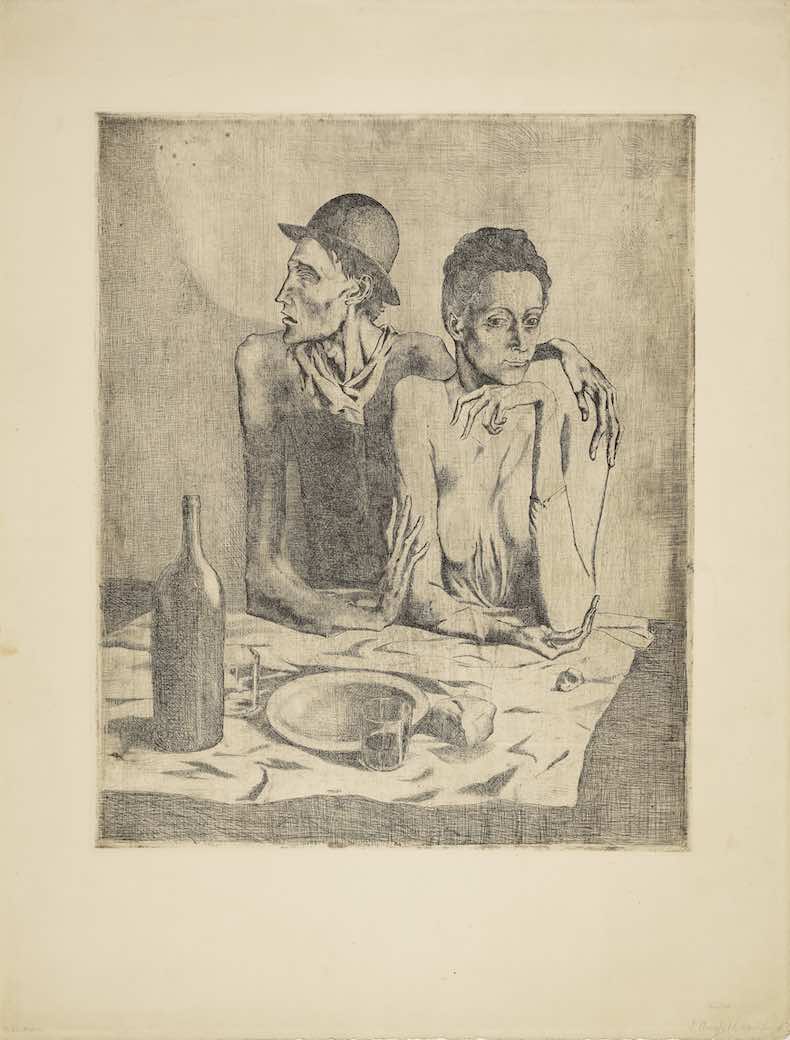

The Frugal Meal (1904), Pablo Picasso. British Museum, London. Photo: © Succession Picasso, DACS, London 2024

On show is The Frugal Meal (1904), the first print Picasso made in Paris. A couple at a table sit together but seem distant, morose. In contrast to the emaciated figures, a stolid wine bottle is given prominence in certainty and solidarity. The man’s bowler hat and the accompanying tumblers (his is empty, hers half-full), suggest this wine as an approachable Beaujolais or Côtes du Rhône, drunk by the working classes in Paris. Even thrifty Picasso had to repurpose a zinc plate from a peer, Joan González, a landscape artist, and did not scrape the previous image away, leaving tufts of grass visible in the top right. Perhaps an entry-level oversight, but a propitious mistake nonetheless.

Wine also features in Picasso’s most significant cubist print on display, Still Life with a Bottle of Marc (1911), made by drypoint, an etching technique that involves scratching directly on to a metal plate with a needle, creating burrs that give prints a soft, velvety line. The work is an exemplary still life, with overlapping geometric shapes of playing-card clubs and hearts, simple wine-glass fragments, and experiments with spatial perception and experience. In 1911, marc, a type of pomace brandy made from grape skins, seeds and stems, was fermented in Bordeaux and Champagne and seen as rustic and authentic, unlike the fashionable (and highly taxed) absinthe widely consumed in France. Picasso spent that summer in Céret in the Pyrenees, working with Georges Braque.

Still life under the lamp (1962; detail), Pablo Picasso. British Museum, London. Photo: © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2024

The Vollard Suite, completed for Ambroise Vollard, one of Picasso’s earliest supporters, who gave him his first exhibition in Paris in 1901 and published his earliest prints in 1913, contains 100 plates. The British Museum is one of two institutions to display the full set in public (interestingly, the other is a winery in Jerez, Grupo Estévez). Several works from the Vollard Suite are replete with depictions of Greek mythology, connected to the sacred history of wine in transgressive contexts. The metamorphosis is also underpinned by the artist’s technical innovation through printmaking techniques, which tell another story of transformative change. Certainly, Picasso may have intended to stay Apollonian – orderly and rational – as seen in prints of the laurelled Young Sculptor at Work (plate 46) carving busts or dutifully sketching models (Sculptor Working from Life With Model Posing, plate 59). But increasingly, the Minotaur as a Dionysian force (aided by wine and frenzy) undermines the artist’s control through violent and beastly urges, as in Minotaur Caressing a Sleeping Woman (plate 93).

The bacchanals and wine-induced ecstasy continue in the printmaking of the mid 1950s, when Picasso revolutionised linocut methods to use a single block for printing (requiring precision and foresight). The Bacchanal with an Owl (1959) depicts his mascot overlooking a frantic procession of drinking, dancing and cavorting. From the traditions of classical art to the role of wine in Greek mythology and the alcohol-infused vibrancy of Picasso’s French social milieu, the myriad depictions of wine and alcohol in his work are far from coincidental. This creative transgression, inspiration, and ecstasy is multiplied, cut and printed to be experienced again and again.

From the February 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.