The town of Delft is paved in brick. Its older houses have brick facades; the Markt – the central square – is an expanse of alternating bands of staggered and herring-boned brick, dominated at one end by the Nieuwe Kerk, a church of brown brick. The streets are a training of the eye in patterns of tessellation, segmented spaces, and receding and intersecting lines: the perfect prelude to this revealing and compelling exhibition, the first in the Netherlands and only the second in the world devoted to Pieter de Hooch, an extraordinary painter – and also a bricklayer’s son.

De Hooch was born in Rotterdam in 1629, and moved to Delft in around 1652, when the city was a centre of artistic innovation, home to Johannes Vermeer and Carel Fabritius. He lived there for the next eight years, developing from competent genre paintings of guardroom scenes to a distinctive and inventive style, attentive to the spaces and surfaces of Delft, including courtyard scenes, which he invented. Around 1660 he moved to Amsterdam, where his rate of production accelerated and the quality of his work declined, and died in or after 1679. The exhibition and its generously illustrated catalogue add substantially to knowledge of De Hooch and his methods, through research into his presence in archives, the provenance history of his works, and the composition of the paintings. The major impetus for the exhibition is expressed in its subtitle: though it acknowledges the similarities and relationship between their works, it also argues that De Hooch be seen for his independent achievement, rather than as a minor Vermeer, contributing ideas to the master.

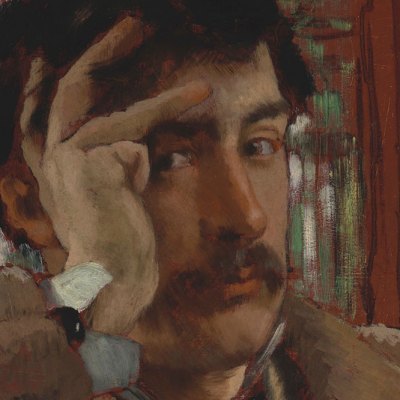

Woman Weighing Gold and Silver Coins (c. 1664), Pieter de Hooch. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. Photo: Jorg P. Andrews

Extracting De Hooch from Vermeer’s shadow involves, paradoxically, comparing the artists. Both exhibition and catalogue invoke sibling pictures to demonstrate De Hooch’s distinct preoccupations. An instructive example is Woman Weighing Gold and Silver Coins, whose composition inspired Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance (both c. 1664). The paintings are manifestly similar in subject; the differences, however, are telling. Vermeer’s woman, beautifully illuminated by light from a high window, has a look of Marian peace and absorption. Her scales are empty and level, while her hands, the right suspending the balance, the left reaching for a coin, counter the equal scales with an exquisitely poised asymmetry. The painting of the Last Judgement behind her invites symbolic readings of weighing and of finding wanting.

De Hooch is much less interested in the central figure. Her face is almost occluded in her hood, and her shape concealed by voluminous clothes. As the catalogue essay remarks, the primary colours of the wall and clothing render the composition almost abstract. Pattern asserts itself in the squares of gilded leather wall coverings, and the folds of decorative carpet in the foreground. A doorkijkje (a glimpse through a door to a space beyond) reveals rectangular forms: a tiled floor, a door, a wall hanging, a grid of light from an unseen window. The two foreshortened windows on the left, one ajar, add an exercise in grids, perspective, and sharp angles. The foreground collapses into the background, where the studs on a chair and the gold of the wall reiterate the supposed subject of the painting, the coins the woman is weighing.

The Courtyard of a House of Delft (1658), Pieter de Hooch. National Gallery, London

This emphasis on pattern over person is typical. All of the 29 works displayed in the exhibition involve human figures. But the figures are formulaic. A dozen paintings feature a woman standing with inclined head in a cap, coloured skirt, and apron, holding something in her hands (a bucket, a basket, the hand of a child). Analysis of layers of overpainting has demonstrated De Hooch’s tinkering, exposing figures erased or moved during the process of painting. The people are an afterthought. Woman Weighing Gold and Silver Coins originally had a man sitting where the carpet now rests; a pentimento which argues that De Hooch’s painting preceded Vermeer’s. The top layer of paint in Interior of the Council Chamber of Amsterdam Town Hall (c. 1663–65) has faded, so that pentimenti, including a ghost dog, are visible, while floor tiles show through the legs of a foppish figure in yellow. Though an accident of time, it expresses the real sense that De Hooch’s human figures are temporised obstructions of geometric form. His paintings resist narrative. It is difficult to imagine a novel, a Girl with a Pearl Earring, written in response to De Hooch.

Instead: pattern, grids, and light. Almost all of the Delft scenes, indoors and out, involve a threshold at which a plane segmented by one form meets another: a floor tiled in diamonds gives way to one of squares, or tiles meet brick. (A note in the catalogue observes that Vermeer only used tiles laid in diamonds; De Hooch’s contrasts are idiosyncratic.) Most involve doorkijkjes, a compulsive motif for De Hooch. In Woman with a Child in a Pantry (c. 1656–60), a door gives on to a room in which a window gives on to the street. The receding apertures give partial views of other spaces, reduced to line and colour. In the Bedroom (c. 1660–62) offers a particularly inventive study of lattices, where the grid of the interior window intersects with the glass of the outer door and fences beyond it. De Hooch’s doorkijkjes embed abstract compositions within the larger frame.

Woman with a Child in a Pantry (c. 1656–60), Pieter de Hooch. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The underside of the staircase in Woman with a Child in a Pantry is reduced to intersecting squares and triangles that echo the transition between the tiled floors. The drama of pattern is the painting’s subject, and the woman and child are rendered as incidental as the tiny figures about their business on the Delft tiles skirting the wall. In outdoor scenes, like A Woman and Child in a Bleaching Ground, closely observed Delft landmarks are grouped for form in defiance of their actual topographical relation. De Hooch’s paintings make fictive patterns of fictile brick and tile.

Interior with Mother and Child (c. 1665–68), Pieter de Hooch. Amsterdam Museum

Derek Mahon, in ‘Courtyards in Delft’ – a poem inspired by another study in brick, The Courtyard of a House in Delft (1658) – wrote that De Hooch casts ‘oblique light on the trite’. In Interior with Mother and Child (c. 1665–68), the human figures draw the eye less than the light cast on the back wall, a liquid shimmer barred by a lattice of shadow. The ostensible subject of the painting is subordinated to a fascination with intersecting parallelograms, as the grid of shadow meets a chair and tiles on the fireplace and floor. De Hooch is not a lesser Vermeer. Rather, as this exhibition allows us to experience, he is his own peculiar thing: someone who worked as if painting is like bricklaying, a matter of arranging vertical and horizontal lines, placed to reveal the quotidian delights of pattern framing and illuminating even the most modest domestic scenes.

‘Pieter de Hooch in Delft: From the Shadow of Vermeer’ is at the Museum Prinsenhof Delft until 16 February 2020.

From the December 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.