From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

As I write, I’m looking at a postcard of Masolino da Panicale’s Conversion of Empress Faustina (1425–31) from the church of San Clemente in Rome. It’s an object that for now is propped against a row of books on my desk, in temporary respite from its usual employment as a bookmark. Working from home has lopped the commute and its reading opportunities off both ends of the day, and the postcard consequently looks a little bereft. It’s travelled with me over the years through a number of books and every time it has, the image of the painting has seeped into the reading experience and coloured it.

The postcard shows Saint Catherine leaning casually out of an open window in her prison cell, while the empress sits outside listening intently. On the wall of the chapel itself, just beyond where the postcard stops, the empress is shown having her head cut off, but for whatever reason – possibly the need to sell postcards – the image doesn’t show that part, and suspends the narrative just beforehand, at the moment of the empress’s conversion to Christianity under the saint’s instruction. Perhaps because of that elision, and its implication that the story might end in any number of ways, the postcard has generated new possible meanings in the books it has marked. Having been picked at random to bookmark Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer, for instance, it ended up as an oblique illustration of the text, restaging its theme of the ethics of confidence. And it too has been changed by that transitory relocation, becoming not so much about this saint or that empress, or even this artist or that chapel, but about the idea of communication, teaching, faith and even friendship. Both the book and the image have been made more complex, more fertile in possibility, through this mutual blending, made manifest through the postcard itself being slid into the block of pages.

I’ve been calling this postcard a Masolino, or referring to it in terms of its narrative content, but really it’s a print of a photograph of a section of that painted space. In other words, it’s a reproduction of a work of art that lives its own life independently of the painting itself. It is a work of art in its own right, in fact, with its own visual conventions, histories and complicated authorship. That’s another thought for another time – there’s an art history of postcard reproductions waiting to be written, if it hasn’t already been, for which this article might as well represent a pitch – but for the purposes of this context, I’d like to worry the photograph free of the painting, and worry the postcard free of the photograph, to think about the life of art within our own experiences.

What makes postcard reproductions of works of art so vibrant is precisely their distance from the original source. The photograph of which the Masolino postcard is a reproduction is a record of a particular moment in the long life of the painting. It was taken on a chosen day, perhaps one with an ideal fall of light across the wall. The photographer set his kit up in such a way as to create a flat, face-on image of the painting, parallel to the surface of a postcard, and separate from the context of the other images that surround Saint Catherine and the empress in the real chapel. All kinds of other contexts are shorn away too, of course, including all the sensory data (acoustics, scale, textures, even smells) with which we come to encounter and make meaning of works of art in the wild. Magically elided too is the iron grille that blocks physical access to the chapel itself. The photograph, then, is a token of what it can’t show; its existence calls up absences. All photographs of works of art – upon which all art-history lectures, museum catalogues and art magazines depend – do this, of course. In postcard form, though, the photograph’s glancing relationship to its source does something different.

The Castiglione Chapel in the Basilica di San Clemente, Rome, with frescoes by Masolino da Panicale depicting the lives of Saint Catherine of Alexandria (left wall) and Saint Ambrose of Milan. Photo: Alamy Stock Photo

Above and beyond its intrinsic separation from its source, the postcard reproduction exists to be taken out of context. Divorced from any sense of scale and lacking explanatory text (beyond the untranslated title on the reverse), the postcard is designed to spread beyond the limits of its usual meanings. Its distribution as post provides an easy metaphor for that, if one were needed. Rummaging through a drawer of old postcards, I find many of them have stamps and messages on the back, usually with jokes that retain a certain kind of groaning familiarity. They were tokens of separation, even then. By the time they’d arrived, the friends who’d written them had long since moved on from the places they bought them from; they’d even moved on from the jokes.

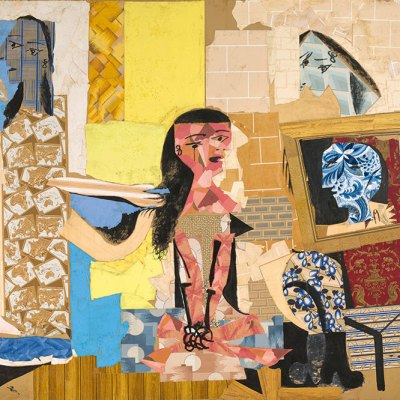

Just as they did in their double life as bookmarks, the postcards’ reproductions complicate the meanings of their sources. A postcard of Picasso’s Self-Portrait of 1907, repurposed as a birthday card, grants the painting a manic friendliness it might not otherwise seem to possess; a recent note from a friend on the back of a postcard of Cy Twombly’s Cabbages (1998) is a reminder of all the dinners that haven’t been had, and of how any dinner, even cabbages, would do. The unused postcards, meanwhile – tokens of exhibitions seen, of trips made – accrue poignancy, now especially, just by being themselves. The disappointment they embody – so unlike what they show, and so far from home – is like our memories of art after a long period of absence: almost faithful, but not quite.

From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.