From the February 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Curator Fan Jeremy Zhang explains how, in the 20th century, the artist Qi Baishi – sometimes called the ‘Picasso of China’ – revitalised Chinese ink painting for a global audience.

Qi Baishi (1864–1957) had an extraordinary life; most people would never have thought based on his humble origins and his late training that he would become a renowned artist. Most painters began training or had shown their talents from an early age, maybe during their teens, but he did not start until he was almost in his thirties, having first trained in carving and carpentry. These days he is remembered as ‘the people’s artist’ for his depictions of mundane scenes, which attracted people from all walks of life. He is also remembered as the last true literati artist, thanks to his four accomplishments – poetry, seal carving, calligraphy and painting.

A number of artistic transformations occurred throughout Qi Baishi’s life, one of which is defined by a series of five departures and five returns that the artist made between 1902 and 1909. He was born in the south of China, in the countryside near Changsha in Hunan, but he travelled widely, in the north as well as the south, experiencing different landscapes and climates across the vast territory of China. During these travels he made a number of sketches from life, and in 1910 he gathered these and created several sets of landscape paintings, including a series of 52 works, Borrowing Mountain from Nature. That title reflects the artist’s belief that he could only borrow beauty from nature rather than possess it. Qi Baishi’s pictures often come with poetic inscriptions; if you read the inscription, you have a better understanding of the image.

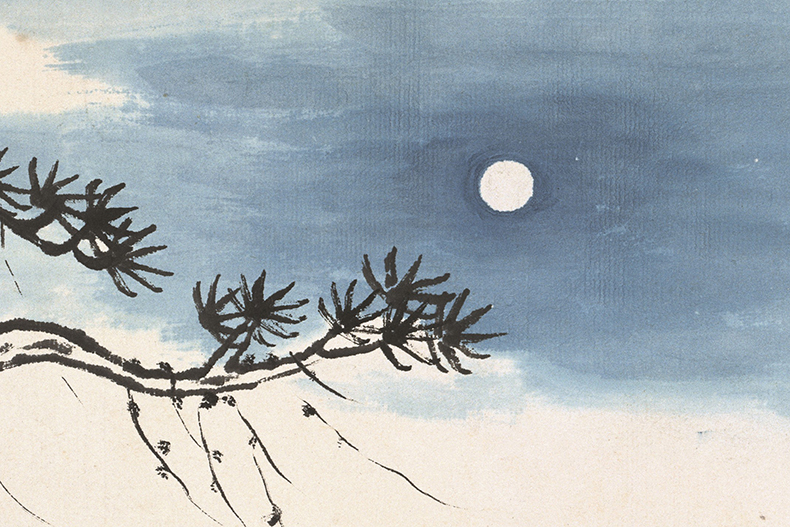

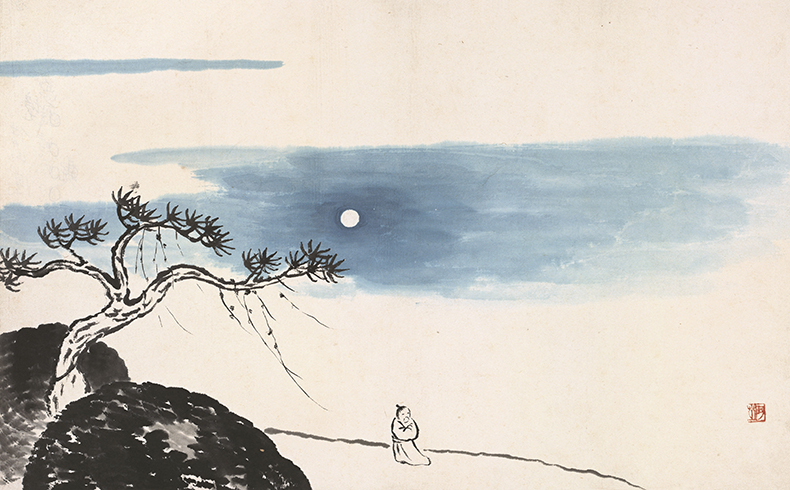

Borrowing Mountain from Nature No. 11 (1910; detail), Qi Baishi. Beijing Fine Art Academy.

This picture, Borrowing Mountain from Nature No.11, is from a set of 22 surviving works from the album that is in the collection of the Beijing Fine Art Academy. You can see that the artist has picked up on important motifs, reducing the image to its basics. In this moonlit night scene – not a common subject for Chinese artists, who would usually prefer to depict day rather than night – the artist has tried to emphasise a windy moment. All you can see is one lonely pine tree, its branches blown in one direction by the wind, along with a lonely traveller who is reluctant to expose his hands and the moon shining through the clouds. The expressionistic and impressionistic qualities speak to Western traditions, though the artist had had little exposure to the West. He uses a very traditional rice paper and ink to emphasis different tones in basic colours – for example, using blue to highlight this cold, late-night scene. We don’t know the specific details or location of this particular painting, but we can guess, based on our knowledge of the artist’s travels, that he would have captured these chilly scenes during trips to the mountains in the north in the late autumn or early winter. The painting also shows the seal ‘A Zhi’, a nickname of the artist.

Qi Baishi was an accurate observer of nature; he was from the countryside and knew the rustic life. His work can be very plain and simple, but this meant that patrons and art collectors could easily recognise this quality of naturalness in his paintings, and it’s to this that many scholars attribute his success. In his depictions of nature, he always discovers something interesting – the joy of everyday life, the pleasure of mundane objects. From his perspective, in his observation, something that may not look so interesting to others always has unique, interesting aspects to convey.

He was an honest recorder of his travels – unlike traditional Chinese ink paintings, his works draw together important moments through selected motifs, focusing on the most memorable elements. The way he has cropped this image is very different from what we would recognise as traditional landscape painting, where we would see a clear foreground, middle ground and background. It’s as though the artist was taking a photograph of his travels – sometimes in his work you will see pavilions or other buildings cropped right through the middle, or he might emphasise a boat or large body of water in the centre of the work. He always appears to make economical choices, only including what impressed him most. The composition, which looks so plain, so naive, actually conveys some very distinctive feelings, and that’s why this set of album leaves sets him apart from other artists. He learned this kind of minimalist treatment from a selection of artists who he studied under and often imitated, notably two monks named Zhu Da and Shitao. The work reflects his own understanding as a carpenter and seal carver: in carpentry, as in painting, you need to remove unnecessary elements and only emphasise the most important motifs.

Borrowing Mountain from Nature No. 11 (1910; detail), Qi Baishi. Beijing Fine Art Academy.

At this point, there were some important artistic experiments seeking to transform the practice of seal carving and calligraphy into pictures, depictions of landscapes – this was the modernisation of Chinese ink painting, which happened in the second half of the 19th century and first half of the 20th, during a period of tremendous social and political strife. The end of the Qing dynasty and China’s 2,000-year-old feudal system had brought forth conflicts, cultural and artistic, between tradition and newly introduced styles. Qi Baishi had not travelled much to the coastal provinces, but lots of individual artists in Shanghai had been exposed to influences from Japan, and were looking for ways of changing the old styles, the old values, the old practices; they wanted to either completely discard traditions or revitalise them for a new era. They were trying to bring ink painting up to date, and one way to do this was to emphasise expressionistic brushwork and dynamic movement and use bold compositions to highlight the presence of ink in the image itself. Chinese painting is very different from Western painting; the art of Chinese ink painting is all about the movements of the brush, and by looking at the rendering of the lines and observing the traces of the brush, the audience can feel the resonance of artistic expression. In Qi Baishi’s art you can see his economy, his spontaneity, the dynamic energy of each individual brushstroke.

In 1919, having achieved a certain fame in his home town, he relocated to Beijing. Initially his art did not sell well, and at the suggestion of one of his friends, the painter Chen Shizeng, he began a period of self-transformation, moving away from simply imitating Zhu Da and Shitao. From 1919 to 1928, he developed a new style that mixed literati and folk influences, highlighting red flowers and ink leaves in his paintings and incorporating the Jinshi (bronze and stone inscription) styles that were promoted by the Shanghai School artists, who were more clientoriented. These more lively and joyful works appealed beyond the small, elite circle of people who appreciated art to a wider audience interested in the declining traditions of ink painting and won him recognition, pushing his prices up. Meanwhile, friends took his paintings to Japan, where his depictions of the micro-worlds of insects, flowers and plants were admired.

Borrowing Mountains from Nature No. 11 (1910), Qi Baishi. Beijing Fine Art Academy.

In Beijing, Qi Baishi also taught, serving as the first honorary director of the Beijing Fine Art Academy. After his death, his family donated hundreds of paintings to the Academy, which consequently has a vast collection of his work. He also met peers from Europe: in 1930 the Czech painter Vojtěch Chytil included him in an exhibition of work by Chinese artists in Vienna, the first of several. Thanks to Chytil’s interest, the Czech Republic now has the largest holdings of works by Qi Baishi outside China. In Europe, Qi Baishi was sometimes called ‘the Picasso of China’. Though the two artists never met, they did exchange works. After 1949, Qi Baishi was promoted by the new Chinese Communist government, which sent Picasso a selection of his work, particularly depictions of fish and shrimp. Picasso was impressed and produced his own drawings of fish and shrimp based on Qi Baishi’s. Meanwhile, Qi Baishi painted his own versions of Picasso’s peace doves – both artists supported world peace movements in the 1950s. Americans also responded to Qi Baishi – notably the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, who travelled to China and studied ink painting with Qi Baishi for six months in 1930. In the 1940s, Qi Baishi’s work was featured in contemporary art exhibitions in Pennsylvania and New York, and in 1960 he was the first Chinese artist to have a solo show at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, of which the Asian Art Museum used to be a part. His overseas fame helped to consolidate his reputation in China, and at the height of his career people were queueing up to buy his work. He knew his own worth: he had a price list hanging in his studio, and apparently met any mention of ‘friendship’ discounts with the suggestion that no gentleman would ask for such a thing.

Qi Baishi has remained a big name in China, and his success lies not only in his talents but also in his diligent practice. The Chinese title of the show is inspired by one of his favourite seals: ‘Old yet strong, I choose not to be an immortal.’ This statement reflects his tireless desire to continue creating in his old age and his refusal to enjoy retirement as a revered figure. Until the very end, he was a pioneer who revitalised Chinese ink painting for a global audience.

Fan Jeremy Zhang is curator of Chinese Art at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

‘Qi Baishi: Inspiration In Ink’ is at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, until 7 April.

From the February 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.