From the June 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Rethinking Guernica’, a digital initiative from the Reina Sofía, is the result of a monumental research effort by the museum’s curators and conservators. This ambitious undertaking has resulted in a comprehensive view of Picasso’s Guernica from historical, art-historical and conservation perspectives. The Reina Sofía’s research is exceptionally rigorous – even including in the oral history section of the site an interview with the Vietnam War protester who vandalised the painting in 1974. For readers yet to explore this project, it may be hard to imagine what new analysis and documentation remain to be presented about Picasso’s great painting condemning the bombing of Basque civilians by German and Italian fascist forces in 1937. Don’t let that stop you: this website is, with a few small qualifications, an exemplary display of in-depth investigation and documentation – covering the political history of the work, its necessarily peripatetic life, and the materiality of the painting.

The technical research that the museum’s conservation department has conducted on the painting can be found in the website’s ‘Gigapixel’ section, which includes massive high-resolution images collected using ultraviolet illumination, infrared radiation, visible light and X-radiography. To assist in registering these images perfectly, so that side-by-side comparisons of the different imaging modalities was possible, the conservation department built a robotic scanner to capture thousands of images of the painting via each imaging method. The results of this intensive effort (the robot moved with a precision of 25 microns, roughly one quarter of the width of a human hair) are breathtakingly detailed images of the painting, which provide new insights into the compositional changes Picasso made as he worked, the painting’s current state of preservation, the effects of its long history of travel, and even residues from the attack it suffered in 1974 (the vandal sprayed the words ‘Kill lies all’ across the picture’s surface in red paint).

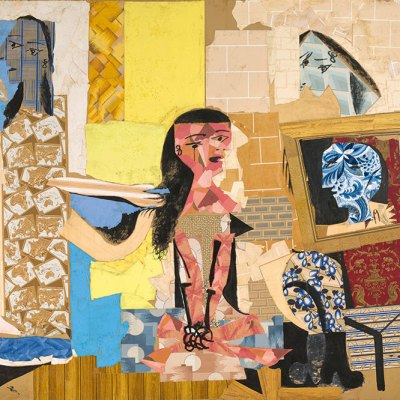

For comparison, the online project also provides access to the Reina Sofía’s incredible collection of Picasso’s preparatory drawings for the work. The ability to study Picasso’s diverse painting methods will be of great interest to art historians and technical art historians: maps of regions of thinned and dripping paint, areas of impasto, details of individual lines, individual brushstrokes, evidence of paint pouring, and the influence of the pattern of the canvas support are all visible here. The alteration maps available for study include diagrams documenting the presence of surface wax from a wax-resin consolidation of the painting’s layers that took place in 1957 while the work was at MoMA, New York, as well as the locations of cracks, fibres, paint losses, stains, micro-cracks, holes, losses, retouching, repainting and surface soil.

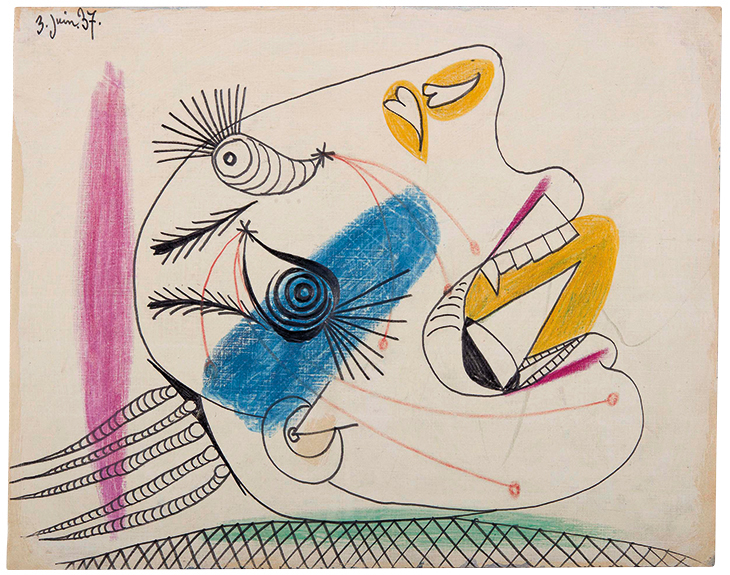

Study for a Weeping Head (I) (1937), Pablo Picasso. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. Photo: Archivo fotográfico del Museo Reina SofÍa; © Sucesión Pablo Picasso/VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

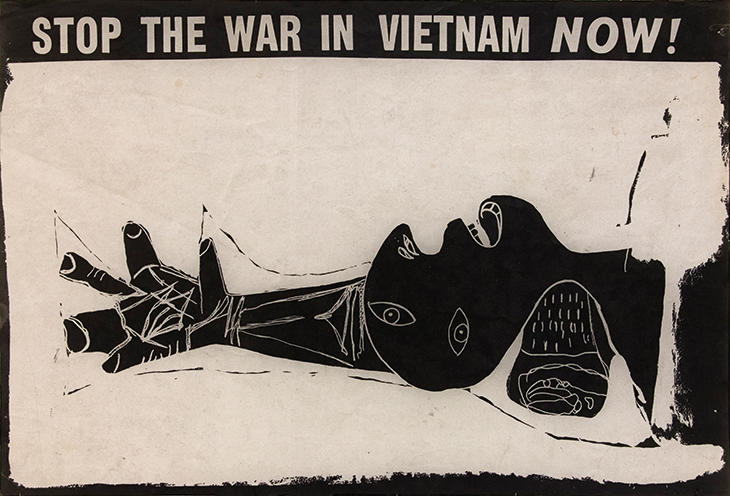

The project’s authors demonstrate Guernica’s 20th- and 21st-century political and artistic influence in exceptional detail, showing how the image, in its totality and in excerpt, has been used in many different protests against war and other forms of human suffering. The wide range of examples includes the use of Guernica at protests against the deaths of Syrian refugees in London in 2016, and against the poisoning of hundreds of Spaniards by toxic rapeseed oil in the 1980s. The website shows how, as a devastatingly visceral depiction of the horrors of war, Guernica has been used in Vietnam and Iraq War protests, its imagery incorporated into posters used to advertise anti-war marches and banners carried by the marchers. The enduring power of the painting – or perhaps the ease with which its elements can be repurposed by other artists and causes – is also documented by the photographer Heinz Hebeisen, who shows it being turned into street art in Madrid in 1982.

Stop the war in Vietnam now! poster (1967), Rudolf Baranik for the Art Workers Coalition

The technical research presented here does have some shortcomings. The data is excellent, but lacks details critical for effective use by experts, while not being sufficiently well explained for the average museum visitor. Information on the painting’s palette and the preparation layers applied to the canvas are, if present, not readily found. This work was painted at a time when Picasso was working in both commercial paints (Ripolin) and artists’ tube paints; without information about the pigments, binding media, fillers and other paint additives present, it is difficult to assess the nature of many of the paint defects observed in the website’s beautifully detailed images. Zinc white pigments can cause problems with paint film delamination due to zinc soap crystallisation, for example, while the anatase form of titanium white pigment can become discoloured and chalky over time. Were either or both of these pigments used here? What about lead white in the warmer-hued whites of the painting? In addition, while the website’s text briefly explains that infrared imaging can be used to study underdrawings, and the ‘Gigapixel’ portion of the site has a useful introductory navigation tool, even a single-page overview of the value of multispectral imaging of works of art, how these techniques work and what information they provide would, I expect, be welcomed by the non-expert viewer. Moreover, while paint defects such as craquelure are mapped and Picasso’s use of pastose versus thinned paints is shown in diagrams, the paint chemistry that would explain how he obtained the different textures observed is missing. If this data could be added to the site, it would make the immensely valuable information collected by the conservation department and so well displayed here even more useful.

Picasso working on Guernica in his Grands-Augustins studio, Paris (1937), Dora Maar. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. © Dora Maar/VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

‘Rethinking Guernica’ also allows the visitor a ‘behind the scenes’ view of the decades of drama and negotiations surrounding the ownership, travel and display of Guernica. Of particular interest is the correspondence of Alfred H. Barr, Jr., director of collections (among other roles) at MoMA, in which he negotiates loans of the work and discusses its interpretation with Picasso and his dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. Picasso stipulated that the work should not return to Spain until the country had been restored to democratic freedom, making Roland Dumas executor of his wishes for Guernica following his death. The return to Spain did not happen until 1981, eight years after the artist’s death, due to objections from MoMA and concerns about the condition of the work, which had been displayed in 11 countries since 1939 (when it was in a travelling exhibition in the United States as war broke out in Europe).

The valuable historical context includes a documentary film that shows not only the heinous war crime that was the painting’s inspiration but also emotive images of refugees fleeing Guernica and Basque children being shipped across Europe to safety. These images provide a prescient and unforgettable sight of what was to come in the Second World War. Like the affair of L’Âge d’Or in 1930 – when the right-wing, anti-Semitic Ligue des Patriotes attacked artworks by Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy and Man Ray during a screening of Buñuel’s film in Paris – Guernica has much to tell us about how the 20th century descended into the madness of a new ‘total warfare’ that included genocide and the intentional destruction of civilian targets.

‘Rethinking Guernica’ allows us to contemplate anew Picasso’s primal response to fascist violence, and to contextualise the rise of nationalism in Europe and the Americas today, and the far right’s renewed attraction to fascist ideologies. This online initiative – along with its peers, such as ‘Closer to Van Eyck’, ‘Operation Night Watch’ and ‘Girl with a Blog’ – is an excellent teaching resource. I will start using it in my classes this autumn.

Explore the ‘Rethinking Guernica’ website here.

From the June 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.