The renowned art dealer Richard L. Feigen has died at the age of 90. Feigen set up his first gallery in Chicago in 1957, later opening in New York where he forged a reputation as one of the world’s leading dealers of Old Master paintings. During his lifetime, Feigen assembled an extraordinary private collection, with particular strengths in Italian paintings, British landscapes and 20th-century German art – holdings that he opened to Apollo in March 2014 when Susan Moore visited him at his apartment in Manhattan. That profile is reproduced in full below.

The veteran New York dealer Richard Feigen would probably claim, like many art dealers, that he is a collector manqué. What distinguishes him from most of his peers, however, is that he has in fact amassed a great private collection. While some dealers who collect have studiously focused on areas outside their commercial interests – the Chicago contemporary art dealer and Old Master drawings collector Richard Gray is a case in point – Feigen collects the types of pictures he deals in but, as he tells me, ‘once they enter the apartment, they almost never leave’.

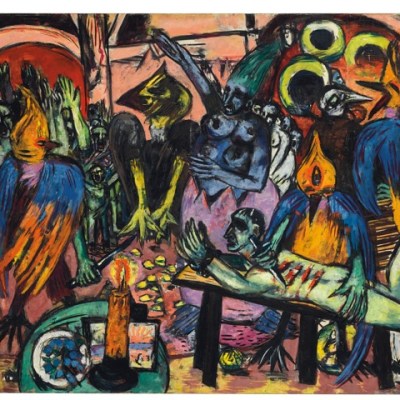

There have always been several facets to the Feigen taste, which is at once catholic and specific, so it is hardly surprising to find a personal collection of paintings that form three distinct groups. The lion’s share is predominantly Italian – or Italianate – Old Masters, but even here the focus is particular: either baroque and mannerist painting, or early Sienese and Florentine gold-ground panels. Next comes a bravura group of British Romantic landscapes. A once larger holding of 20th-century German art is now confined to a small but visceral group of works by Max Beckmann, including the excoriating, anti-Nazi Birds’ Hell of 1938 [editor’s note: Feigen sold the painting in 2017].

Birds’ Hell (1938), Max Beckmann

Richard Feigen has not changed much over the decades that I have known him. He is still lean, tanned, urbane, impeccably dressed – and outspoken. After more than 50 years in the art world, he has assumed the role of elder statesman, and as such can be relied on to tell uncomfortable truths. Several of the targets in his sightlines are outlined in the opening paragraph of his memoirs, Tales from the Art Crypt (Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), which is worth quoting for its flavour: ‘Arrows of barium nitrate pierce the black sky, tracings of invisible bullets aimed at the heart of what we have known as connoisseurship, the love and study of objects fashioned by men. Bit by bit, year by year, the ghostly missiles find their mark and the art crypt fills with casualties of the old order, museums, collectors, artists, those who already love art and those who could have. Anciens combattants, veterans of the culture wars, “elitists” who thus far dodged the bullets, still wander about in daylight hours as the legions of darkness sleep – hack political opportunists, affirmative culture activists, guardians of “family values”, Bible-belting fundamentalists, strategic planners, management consultants, museum headhunters, box-office impresarios …’

Here is someone who evidently cares passionately about works of art, as well as his – and our – engagement with them, and who laments the corporate ‘takeover’ of US museums as much as he abhors the diminished role of connoisseurship in current art history. Certainly his own ‘eye’ – ‘the ability to determine a painting’s authorship through a sensitivity to its aesthetic qualities, like the recognition of a person’s handwriting,’ as he defines connoisseurship – has played a critical role in his success as a dealer and as a collector. Unexpectedly, it was a fascination for the activity of art dealing that came first, as Feigen explains when we meet in his Manhattan apartment.

‘It began when I was about 11 or 12, when a neighbour of ours in Chicago who had an art collection – I remember a major drip Pollock – lent me a book about Duveen. Then when I was about 14, I bought a painting from an antique shop that I thought then – and still think now – was a Jan Brueghel the Elder. That was when I realised that things could be other than what they purported to be, and I began buying things that I thought had quality.’ Another early acquisition was a Ludovico Carracci drawing. He pauses before resuming: ‘Frankly it was the commercial aspect that interested me when I was a youth, but later it developed into a passion where I bought things as a collector. You ask me now how I can do both? I am a collector in dealers’ clothes. I’d rather collect. The only reason why I ultimately went into dealing was because I didn’t have enough money to just buy and buy and keep everything. My gut is in the collecting.’

It took a while to get round to the dealing. After Yale and Harvard Business School, his family encouraged him to go into the insurance business in California. ‘My primary interest was in buying art, but while I was in Los Angeles I was far away from the art centre in New York so I started buying paintings for the chairman of the company and going back and forth,’ he explains. Eventually, in 1956, he bought a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, selling it after six months to set up a gallery back home in Chicago. His own collection of German Expressionists had to serve as the first show: ‘Masterpieces of 20th Century German Art’. The term ‘masterpieces’ was no exaggeration, given that most of the paintings and the single sculpture ended up in museums. He staged the second show of Francis Bacon in the US, in 1959. In 1965, he opened the first art gallery in New York’s SoHo, and moved to the city a year later.

‘Back then I even represented one or two artists – something I gave up long ago,’ Feigen chuckles. ‘In order to promote something you have to be totally committed to one period – you can’t be all over the place otherwise you have no credibility. I also remember trying to straddle the two worlds – being downtown in my SoHo clothes and then rushing uptown [to a second gallery he had already opened in 1962, devoted to Impressionist and early modernist masters] and putting on a tie. Also, I just wasn’t very good at it.’

Revealingly, all of his contemporary artists – from the Surrealists and Joseph Cornell to Claes Oldenburg and beyond – were in revolt against the cult of abstraction preached and practiced in New York. Says Feigen: ‘I represented artists who I felt were saying things that hadn’t been said before. In fact, the only things that I’m interested in – whether they were painted 700–800 years ago, or seven or eight years ago – are by artists who are saying who are cutting edge. It’s my theory that nothing great was ever painted that was not on the cutting edge when it was done, and that if it was on the cutting edge when it was done, it’s on the cutting edge today.’

He draws no distinctions between buying works of art for his gallery, a museum or himself. ‘I am not going to recommend something to a museum or a private client that I would not like to own myself,’ he exclaims, shocked by the suggestion, and explaining that he spends most of his time these days working with museums ‘trying to fill what I perceive to be holes in [their] collections’. Evidently, he is a frustrated would-be museum director too. ‘Whatever I am doing, I am collecting.’

‘Deciding whether to buy something for myself or for my gallery is often just governed by where I happen to have any money at the time,’ he continues. ‘It is also governed by which areas are basically neglected by the market, and therefore afford me opportunities to get things of the first order – and if there are areas here that I like a lot, I have an insatiable appetite. Look at all those Boningtons,’ he says, gesturing to the wall behind me. ‘I love Bonington – I tried to interest the Metropolitan Museum of Art in them but they weren’t interested. They were so Francophile at the time. My only competition then was Paul Mellon.’

Richard L. Feigen photographed at his apartment in Manhattan in January 2013. Photo: Anna Schori for Apollo

The Boningtons flank an impressive Turner: Ancient Italy – Ovid Banished from Rome of 1838. ‘When I was lucky enough to get that Turner in 1974, would you believe that there were people who even questioned whether Turner was a great artist or not?’ His incredulity remains. ‘I would have loved to have bought that great Constable that came up recently, The Lock [1824],’ he continues. ‘If I had the kind of money that some of my friends have, I would have snapped that painting up and it would never have left my home.’ He shakes his head. ‘I exhausted myself trying to persuade the Met to buy it because it was a transformational painting. That will be the last great Constable to come on to the market.’ He is particularly fond of one of the artist’s consummate sky paintings on the adjoining wall.

Feigen was able to form an impressive collection of baroque and mannerist pictures because, he explains, ‘a lot of the directors of the great US museums were Calvinists who did not much like the Sturm und Drang of these paintings. New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Chicago, Boston and Cleveland are weak in this field to this day.’ He adds: ‘there were more people interested in baroque pictures 25 years ago than there are now’. His group ranges from a small Domenichino landscape picked up for 160 [pounds sterling] at an antique shop in Stow-on-the-Wold in 1973, and jewel-like oils on copper, to Orazio Gentileschi’s monumental Danaë and the Shower of Gold of 1621–22. This tour-de-force of surface and texture is currently on loan – and filling a gap – at the Met [editor’s note: the work was acquired at auction by the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2016].

As for the gold-ground paintings: ‘I had never looked at them intensely enough when I started out, but I’ve come to find them increasingly compelling.’ When he began acquiring these panels, there were just two Italian competitors who then passed away. Now two new dealers have entered the fray, as well as one collector, Alvaro Saieh, who has become the greatest of them all. ‘If Alvaro wants something, I just can’t compete with him. I can only get something now if he doesn’t spot it.’

14th-century Italian panel paintings displayed in Richard L. Feigen’s dining room in January 2013. Photo: Anna Schori for Apollo

Vision of Saint Lucy (c. 1427–29), Fra Angelico

Any sympathy one might have evaporates when Feigen opens the door to the climate-controlled dining room downstairs. Against dark mahogany panelled walls, gleaming trecento and early quattrocento panels hang in serried ranks on all four sides (four more panels are still in conservation). The breathtaking, magical effect is akin to being inside a jewelled casket, with the gems fixed to the wrong side. Here, for example, are no less than three panels by Fra Angelico, including an infinitely beguiling Vision of Saint Lucy of c. 1427–29. This had turned up unannounced at a secondary sale at auction in London. ‘I had worked out where and when it was painted – Florence, around 1425–30. Whoever the artist, he was fully aware of Brunelleschi’s perspectives, which were brand new at the time. How many artists could have absorbed this by then?’ He had owned it for a year before Laurence Kanter, now Chief Curator of Yale University Art Gallery, identified it as Fra Angelico and a missing panel from a famous predella. (Kanter, along with John Marciari, subsequently catalogued the Italian paintings from the Feigen collection when they were exhibited at Yale in 2010.)

Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Peter and Paul, and Ten Angels (c. 1330–35), Lippo Memmi

Another favourite is the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Peter and Paul and Ten Angels of c. 1330–35 by the artist that Vasari called Barna da Siena but who is now generally agreed to be more correctly identified as Lippo Memmi, one of the most original and expressive artists of the period. ‘These young girls are all gossiping and the artist is very explicit about his sexual preferences, so he is pretty far out. It is a remarkable painting in a remarkable condition by an extremely rare artist.’ Other powerful, emotive panels include Giovanni di Paolo’s Christ as the Man of Sorrows (1460–65) and the pair of panels by Orcagna, The Deposition (c. 1360–68) and The Entombment (c. 1360–65).

Above the chimneypiece is another highlight: Annibale Carracci’s tender Virgin and Child with Saint Lucy and the Young Saint John the Baptist. Unusually, it is also on panel, executed c. 1587–88, after the artist had worked in Parma and come under the sway of Correggio. He had bought it catalogued as a work by Sisto Badalocchio. ‘I’m gratified if a discovery is endorsed by other specialists or scholars,’ says Feigen, noting that the jury is still out on the attribution of what he believes to be two early works by Poussin.

Virgin and Child with Saint Lucy and the Young Saint John the Baptist (c. 1587–88), Annibale Carracci

‘I like to see my taste vindicated,’ he goes on to admit. ‘You know, I went out to Minneapolis recently and I see what is the pride of their contemporary collection, an outstanding Francis Bacon pope of 1953, one of the big ones and one of the best, which I sold to them from the show in 1959 for $3,500. Now someone might say “you must be kicking yourself”. No, I’m very proud of the fact that the then curator [of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts] Sam Hunter listened to me.’ He continues: ‘In Berlin recently I saw a magnificent red Rothko [Reds no. 5] juxtaposed very intelligently with two works by Giotto, an artist Rothko particularly admired. I looked back and found I had sold the Neue Nationalgalerie that Rothko in 1967 for $22,000 – a painting I would estimate now at least at $50m-$60m. It was an important acquisition for the museum.’

He is relaxed about the art he has failed to buy, but he deeply regrets the rare instances – only around five – when he has sold works of art from his own collection. ‘My reasoning for selling more or less escapes me – I didn’t ever need the money but I sold things around the time I was divorcing or remarrying and I must have thought that I wanted some liquidity.’ Among them was the great Metropolis painted by his friend George Grosz in 1916–17, which he sold to the late Baron Thyssen in 1978; another was Turner’s Temple of Jupiter Panellenius Restored (exhibited 1816). ‘The smart guy is the one who bought it, the idiot is the one who sold it. Every single time I sold something out of my collection it was a blunder. I couldn’t possibly find anything comparable with the money. I had to pay almost 40 per cent of the money for the Turner in tax anyway.’

‘Great objects have become scarcer and scarcer in the marketplace and it is not a question of money. If you asked me to buy a great Matisse for you, I couldn’t produce one, no matter how much money you had. In every Old Master paintings sale in the past, there would have been one or two world-class paintings. Now there are none.’ Even so, he believes that the number of potential buyers will increase across all fields. He talks of the tremendous influx of liquidity in the art market, as people are assured that it is a good place to park money. ‘Every time there’s another contemporary auction, there’s an escalation in price – for Bacon, Warhol, Koons – and people feel it will just keep on, and so they dump more money in it. People are buying with their ears. Even in the early 21st century, people are less discerning and seem prepared to put a great deal of money into a late Picasso or a late de Kooning, painted either when their imaginations had long since evaporated or they were gaga. It doesn’t matter what the thing looks like. It becomes fashionable because it’s expensive.’

‘Intelligent people see what else they can buy for their money, but they are rare. Most people have no knowledge of any other market, and even if they do, they don’t know whom to ask – although there is very good counsel to be found in the museums in New York.’ He adds: ‘There are areas now that are still neglected,’ citing a recent multi-million dollar sale of a great medieval tapestry to a contemporary collector, and his own recent medieval art shows, organised in collaboration with London dealer Sam Fogg. ‘A number of contemporary artists are stashing their loot in Old Masters or medieval, and I have been able to convert one or two contemporary collectors, but it is a slow process.’ There will, at least, be more opportunities for Richard Feigen to add to his inventory.