As far as we know, Romare Bearden made no works of art during his nine-month stay in Paris in 1950. And yet, it may have been one of the most creative periods of his life. He bought an easel and set up a studio but found himself blinded by inspiration. He made pilgrimages to the studios of Picasso, Braque and Brâncuṣi. He rubbed shoulders with contemporaries such as James Baldwin and Orson Welles, spending his days studying philosophy at the Sorbonne and late nights in cafes, parties, and – crucially – jazz clubs. It was everything you would imagine the mid-20th-century Parisian art scene to be – ‘a thing of dreams’, Bearden said.

In subsequent years he slogged through a mostly unsuccessful period of abstraction, striving to reconcile experiences and influences that were as scattered as the collagist style that would later make him famous. In addition to being an artist, Bearden was a semi-professional baseball player, a student of math and science, a cartoonist, a social worker and a jazz composer. In response to the American civil rights movement, Bearden assembled a group of Black artists, called Spiral, to discuss and create artwork that would bring the Black community together. In an early meeting, he dumped a bag of fragmented photographs on the floor and suggested they make a collage together. No one joined in, so he did it on his own.

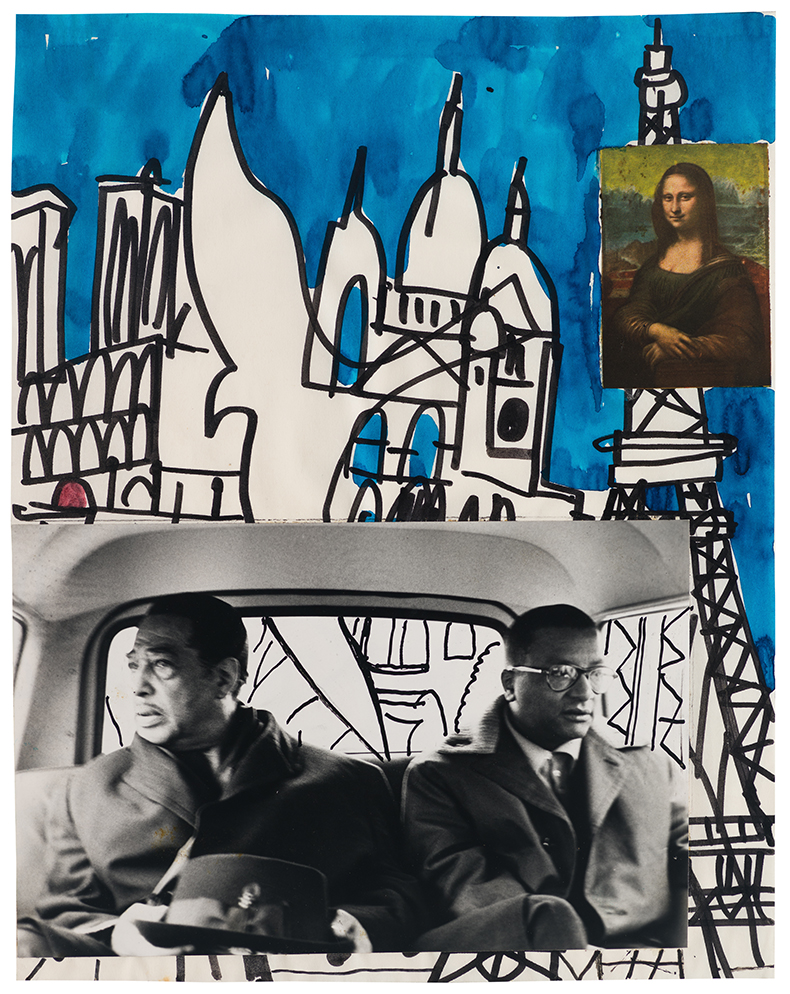

Ellington, Billy Strayhorn (Sacre-Coeur) (1981) from the Paris Blues/Jazz series. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery

Thirty years later – when he had become a star of the art world, and had had a retrospective at MoMA, among other accolades – Bearden turned to his time in Paris for a book of collages about the formative experience of being a young Black artist in the City of Light – overwhelmed by stimuli yet relieved by the relative lack of racial discrimination. His collaborator, the photographer and film producer Sam Shaw, had tried to tackle the same subject 20 years earlier in the movie Paris Blues. But Hollywood executives, afraid of what the public might think about a film about a Black painter, encouraged Shaw to replace the protagonist with a white trombonist (Paul Newman) and relegated the Black experience to a side character (a saxophonist played by Sidney Poitier). While Bearden and Shaw’s book was never finished, the collages survive and stand triumphantly on their own. All 19 of them are currently on view at DC Moore Gallery in New York, alongside a greater number of works from other points in Bearden’s career. When this show closes, they will travel to the Centre Pompidou.

The opening sheet of the series shows a black-and-white photo of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn entering Paris in a taxi, surrounded by a magic-marker drawing of the city with an image of the Mona Lisa – seemingly a stand-in for all of art – looming over them like a spectre. The main character in Bearden’s collages seems to be Ellington, a man already so legendary that the whole cast and crew would applaud every time he came on to the Paris Blues set to compose the score. Even the Duke can start fresh in Paris, looking out the car window bewildered by uncertainty and the daunting artistry of the city.

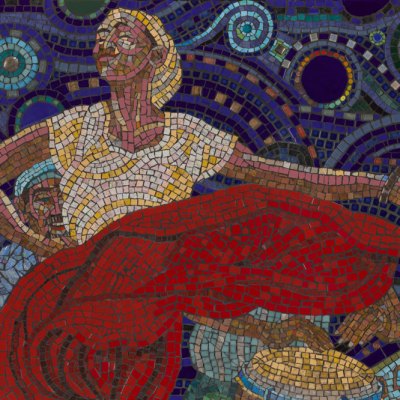

Paris Stairs (1981), from the Paris Blues/Jazz series. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery

The next few sheets take viewers on the kind of jaunt where everything foreign seems magical. Paris Stairs takes a cock-eyed picture of a staircase and brings it to life with a swipe of yellow watercolour and an opposing collage of multi-coloured construction paper creating a slanted spelling of the title. The viewer is soon immersed in the freaky, sultry side of Paris – acrobats and dancing semi-nude women – before returning to the United States with our heads still spinning.

Bearden’s other collages, outside of the Paris Blues/Jazz series, usually position the viewer as an audience member of a musical performance, as in Riverboat Musicians, where a quartet is shoved into the bottom left corner amid blotches of blue paint that overlap and blend in a chancy fashion like the mixing of instruments in a jazz number. Paris Blues/Jazz, by contrast, throws the viewer into the mind of the artist. The images are jumbles of personal and creative life. In one collage of New Orleans, a faceless musician (perhaps a stand-in for the viewer) is coupled with a piano in a living-room-cum-performance space, populated with naked ladies and a chandelier, framed by a red beaded curtain. In another, Louis Armstrong is squeezed into a tight sliver in the right-hand corner, which Bearden learned from studying Chinese calligraphy is the ‘open corner’ where the viewer is invited to enter the composition.

Ellington, Auric, Hodier (1981) from the Paris Blues/Jazz series. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery

With so much going on in each collage, Bearden visually mimics the alluring cacophony of live jazz. Surrounded by sound, we are caught in the crossfire of a battle royal between high hats and thumping bass, while a wizened trumpet wants to sit us down and have our attention. Photographs of musicians are coloured with fluorescent green paint, as if beamed down from another planet. Matisse-like cutouts of figures prance about. By the time we arrive in New York – see the signs of famous jazz venues such as the Apollo, Smalls and Connie’s Inn – the energy that has been mounting throughout the series breaks out into explosive reds and yellows, with musical scores diagonally cast across the page. In the final New York scene, the viewer is placed precariously high, overlooking the skyline as if we might suddenly tumble over the edge into the bright lights.

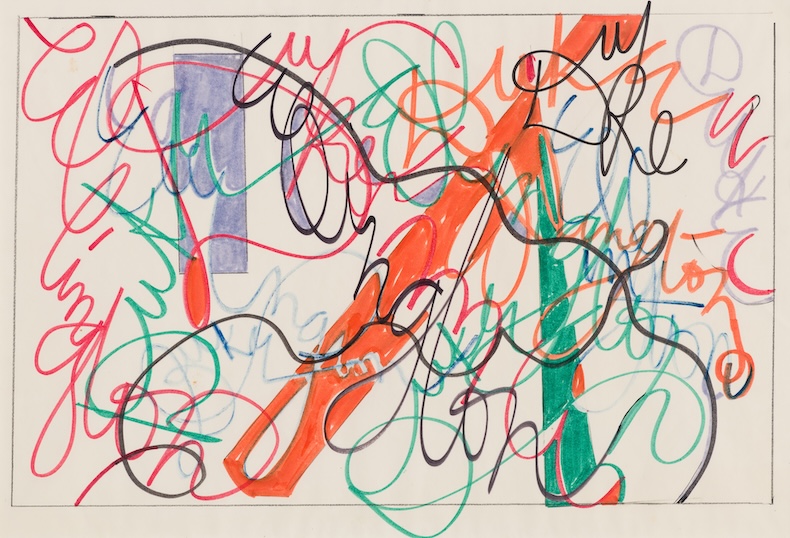

The concluding three pages include two abstractions of swirling lines, followed by a childish drawing of two trains, chugging after each other with trails of smoke. What at first appear to be randomly looping and intersecting lines are actually cursive spellings of ‘Duke Ellington’ and ‘Louis Armstrong’ repeated multiple times on their respective pages – channelling the chaos of the preceding collages into unruly but contained compositions. The trains could recall Bearden’s childhood, when one of his favourite pastimes was watching locomotives trail by, or perhaps the sound of trains – a commonly cited influence on jazz standards – could be one final dedication to the two titans of jazz, Ellington and Armstrong.

Graffiti (Duke Ellington) (1981), from the Paris Blues/Jazz Series. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery

In Paris Blues/Jazz, Bearden throws us into the belly of the beast in a way that nothing quite could have prepared us for. It’s disorienting at first to situate yourself in the world of blues, but it’s the sort of thing you learn by doing. Bearden once said that in Harlem, music infused every aspect of life – ‘the way you stood […] the way you drove an automobile or even just sat in it, everything you did was, you might say, geared to groove’. You may be left speechless, but if you can feel the rhythm in Paris Blues/Jazz, you’re on the right track.

‘Romare Bearden: Paris Blues/Jazz and Other Works’ is at DC Moore Gallery, New York, until 18 January. The Paris Blues/Jazz series can be seen in ‘Paris noir: Artistic Movements and Anticolonial Struggles, 1950–2000’ at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, from 19 March–30 June.